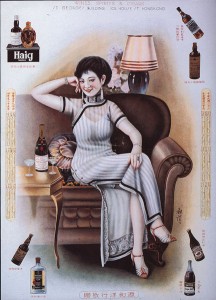

Annie May Wong in the 1934 film “Limehouse Blues”

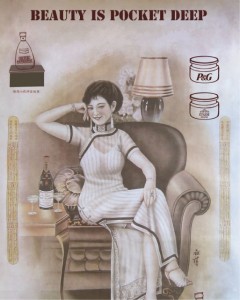

“Daughter of the Dragon” featuring Anna May Wong (1931)

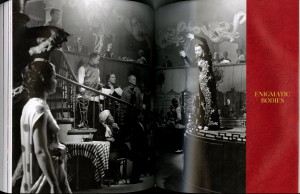

In our presentation, we addressed the question as to how the body of the Chinese woman is seen as exotic and sexy in Western filmography, and what symbolism is used to achieve this image of the Chinese woman as being mysterious and intriguing. Looking through each of the pictures in the enigmatic bodies exhibit, it became evident that the symbol of the dragon was overused and exaggerated to perpetuate this sense of mysticism we as westerners associate to the Chinese women, and more often than not, the body used to perpetuate this association was that of Anna May Wong, the first Chinese film star in Hollywood. It became evident that the dragon became a key indicator of the Chinese “other” for Western consumers, a symbol that has persisted to symbolize an otherness between the East and West in the past and today.

yes, the symbol of dragon but explain why so?

The first image in the collection seemed to characterize perfectly the stereotypical western view of the eastern other we observe in Hollywood filmography of this time. The photo is a sequence taken from the 1934 film Limehouse Blues, which features Annie May Wong as a supporting actress. Our eyes are immediately drawn to the Chinese dragon woman taking the stage, her body captivating the entire audience, which predominately consists of westerners. She is different from them; the dragon body raps around her gown, almost making it look like her face is that of the dragons. Her presence on the stage almost makes it seem as though she is subordinate to the westerners in the audience, and merely there to entertain their gaze and fascination with the exotic otherness she embodies. The dragon is again pushed forth onto the audience as a symbol of a Chinese ethnic other as it is plastered across all the walls, making the restaurant different and mysterious.

Again, Annie May Wong and the dragon are pushed towards us as indicators of a mysterious Eastern other in another photo in the exhibit entitled “Daughter of the Dragon” from 1931. She is shrouded underneath the dark ominous shadow of the dragon that seems to overtake the entire picture. Perhaps the dragon is meant to be her own shadow, making the association between the Chinese woman and the dragon even stronger. She isn’t scared; rather, she is a daughter of the dragon. She further perpetuates this exotic intrigue that the Chinese dragon lady portrayed in early Western filmography.

the connection between the image of “dragon lady and the fashion/costume?”