The film, The Last Emperor, brings to light the story of the last emperor of China. A significant focus of this movie lies in the time period in which he was taken as a child and put into this life. The three year-old has incredible power and the film does a great job using visual cues to signify this point. Through the Emperor’s robe, the color yellow, the mass amounts of people, and the cricket scene, we can see that the movie did a create job creating a clear contrast between the emperors young age and its incredible power that he has.

The Traditional Emperor Robe:

It’s details: This scene image shows the three year-old Emperor dressed in the traditional robe. The details are extremely intricate and carefully woven, demonstrating high class. It clearly could only be worn by a wealthy member of society.

It’s size: The robe is clearly very large and oversized when put on the Emperor. This highlights the Emperor’s youth and contrast between his young age and the incredible power and influence he already has.

The color yellow: The color yellow is extremely prominent in this photo. There is a lot of yellow in the dress as well as in the background. During this time in China, only leaders could wear yellow. In this photo, this color signifies the power and leadership that the boy has.

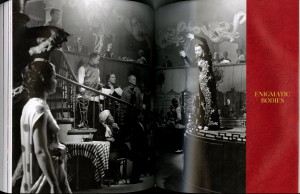

The Mass Amounts of People: The second photo shown displays the emperor standing in front of a crowd of thousands of people. The people are lined up in straight lines and all bowing down to him. Again, this symbolizes the vast power and control the emperor has. This photo also does a good job emphasizing how young the boy is by having him stand in front of this large crowd. Every person is bowing down to a three year-old boy, who is perhaps too young to even read. Overall, it shows China’s dedication to tradition and unwavering commitment to their cultural processes.

The Cricket Scene: In the scene with the cricket, the boy Emperor can hear a cricket noise. He walks down the aisle of people bowing down to him in order to find out where the noise is coming from. He finally finds a man who looks like he is from the lower class, based on his raggedy clothes and lack of detail in his overall wardrobe. His face is fascinated when he sees the cricket. This scene further displays the emperor’s youth and his hunger to be a kid. Hearing a cricket and seeking it out allows for the viewer to see his real age being played out. It also brings up sadness in the viewer because it shows a contrast between the live he has to live while being an emperor versus the life he wants to live out as a child.

Each of these photo or scene cues demonstrates a contrast between age and power. The three year-old is so young, naïve, and still has so much to learn, yet he is leader of China.

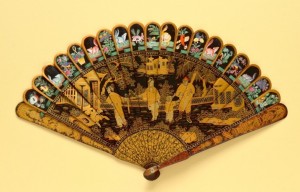

Brise fan made in France c. 1830 – 1840

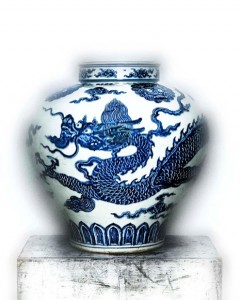

Brise fan made in France c. 1830 – 1840 Jar with Dragon. Early 15th Century.

Jar with Dragon. Early 15th Century.  Evening Dress, fall/winter, 2005-6. This piece was inspired by the Jar with Dragon.

Evening Dress, fall/winter, 2005-6. This piece was inspired by the Jar with Dragon.