The Search for Patrons: An Overview of American Artistic Institutions & Critical Discourse in Nineteenth-Century New York City

Nineteenth-century New York was a rapidly growing port-city that connected the rest of America to the transatlantic continents of Europe and Asia. As the city underwent vast economic expansion, the burgeoning middle class wanted to learn about arts and culture, and moreover, the high-class American, was striving to achieve taste. Whether this ‘taste’ was interpreted to diminish in value with its democratization differed based on the various ideologies surrounding art, its worth and purpose in nineteenth-century America. In many ways, these ideologies were manifested in the variety of cultural institutions, unions, associations, and clubs that sprung up alongside the commercial galleries, which combined to create the thriving art scene characteristic of twentieth-century Manhattan. In the 1840s and 50s, emigrants brought with them artistic technical knowledge and heritage, while the emergence of the American department store marked a turning point in the climb of consumer experience and the sale of luxury. The subsequent rise in print media played an important role in educating the American public—including cities like Philadelphia, Chicago, and Boston—on the artistic discourse surrounding foreign art, and introduced them to new perspectives. It is in this context that American artists attempted to gain a foothold to contend with European art and its rich lineage which stretched back centuries before the foundation of the United States itself. This thematic essay will investigate the role of institutions and periodicals which promoted and reviewed artistic events, to understand their relationship to the development of a nationalistic art movement in nineteenth-century America.

Establishing The National Academy of Design

The National Academy of Design was founded in 1826 by artists like the American landscape painter Thomas Cole, as a concrete way to legitimize the profession and identity of the American artist in particular. Organized and directed by artists for artists, the Academy was interested in training and promoting younger generations while generating market value for contemporary American art.1Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 37. However, the formation of the National Academy was especially significant because it allowed artists to claim professional authority in matters of artistic taste. Its president from 1826 to 1845, Samuel F. B. Morse, structured the organization by selecting thirty full-time artist-academicians that served to elect associate members, admit students, and screen the submissions for each annual exhibition.2Rachel N. Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City: The Rise and Fall of the American Art-Union,” The Journal of American History, 81, no. 4 (March 1995): 1536. This was reflective of Morse’s own belief that national art’s only way forward was if artists maintained aesthetic authority alongside the support of the educated elite.3Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1536. Beginning with their annual exhibitions in May 1826, the Academy displayed works not previously shown to the public and provided an alternative market for those concerned with the authenticity of old master works imported from Europe.4Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 37. The Academy indirectly fostered patronage, establishing a social network between academicians and wealthy patrons by offering an honorary membership to aristocratic art viewers.5Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1536. This institutional structure did little to generate sales, as the majority of works exhibited were borrowed from private collections and most others failed to find purchasers.6Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1536. However, the Academy’s nineteenth-century annual exhibitions served as an important platform for American artists to display their work, the content of which were usually landscapes or portraits of the patrons frequenting them.

The Academy not only exhibited American art in the nineteenth-century—at the outset of which, dealers could not make enough money running a business that specialized in its sale—but it as an institution also took on the broader task of educating the American public on art’s significance and value, especially in its preliminary years. Given the lack of discourse on American art at the beginning of the century and even later on, American artists had to take on the task of defining their art and its importance. Although the economy was prosperous at its founding, the late 1830s were a time of economic hardship, and it would not be until the mid-1840s that the economy would recover, marking the increase in young men who aspired to be painters.7Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 39. At this time, there was also a shift in the focus of New York art collectors from old masters to contemporary European and American art.8Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 40. A branch of the French firm Goupil, Vibert and Co. set up shop at 289 Broadway alongside other commercial art galleries, and was involved in the manufacture and sale of European prints as well as contemporary French paintings.9Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 40. Goupil’s earliest New York employees—Michel Knoedler and William Schaus—would go onto open their own shops and become some of the most influential dealers in the nineteenth-century American art market. Emigrants from Europe throughout the 1840s and 1850s played a huge role in shaping the city, as they brought with them both technical artistic knowledge and a rich cultural heritage that emphasized the importance of art in society. However, while European art served as an important influence in the development of an American lineage, it also undermined its demand. The Academy had a particularly difficult position to reconcile, as it attempted to craft and elevate a distinctly American art, at a time when America was learning from Europe and its rich cultural and artistic legacy.

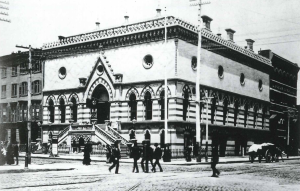

Figure 1. Peter B. Wright, The National Academy of Design, Twenty-third Street and Fourth Avenue, 1863-1865.10Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 43.

The American Art-Union (1839-1852)

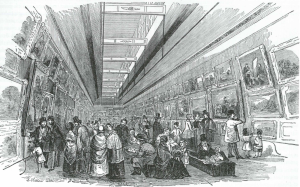

Founded in 1839 by American merchants and professionals committed to promoting art to moralize the public, the American Art-Union was an important art organization that eventually boomed alongside the economy in the late 1840s. The Union grew out of James Herring’s Apollo Gallery when he failed to meet his expenses. He called a meeting of gentlemanly art enthusiasts, whom ultimately joined Herring as managers in raising capital by selling five dollar annual subscriptions.11Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 41. In exchange for their fee, they “published a magazine, commissioned engravings, and purchased recent American paintings and sculptures that were put on display in the organization’s exhibition room.”12Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 41. The managers of the Art-Union refuted the Academy’s claim to artistic professionalism and authority, excluding them from the manager position in fear that they would politicize art’s purchase.13Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 41. Members of the Art-Union were not charged for entry into the exhibition—while a one-time ticket for a non-member was 25 cents—and they received a magazine subscription, as well as a copy of the year’s engraving and a chance in the lottery to win one of the artworks.14Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 41. As the value of American paintings increased in the late 1840s, alongside a prosperous market, subscriptions followed. In 1848, the Bulletin of the American Art-Union featured an article about Thomas Cole’s series “The Voyage of Life,” declaring that its initial purchaser had paid six thousand dollars for the paintings.15Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1547. The Bulletinwent on to suggest that no other institution had offered Americans the chance to win such a valuable prize, and the public’s knowledge of this should result in a massive increase in subscriptions.16Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1547. In somewhat of a self-fulfilling prophecy, subscriptions rose from 9,666 in 1847 to 16,475 the following year, as the Art-Union offered hundreds of prizes from its extensive collection of artworks.17Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1547. Despite its commercial affiliation and nature, the Union was not profit-seeking, with all of the organization’s profits channeled directly to supporting American artists.18Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1549.

The Art-Union’s emergence signalled the arrival of a European model of artistic patronage, one that participated in the production of artistic discourse through publications and subscriptions in attempts “to liberate artists from dependence on private patrons while enlisting art in the reformation of public life.”19Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1537. Modelling themselves off of Edinburgh Art-Union, which in-turn was influenced by those in Germany and Switzerland, the American Art-Union participated in the European tradition by creating an organization that promoted state sponsorship for the arts at a moment when there was none.20Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1537. This model championed art’s democratization, joining democrats and conservative Whigs in a mission to diffuse a cultural taste, which would help develop morality within American public life.21Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1537. The organization illuminates the cultural politics and debate surrounding American art’s place in the antebellum North, as supporters of the Union cited private enterprise’s inability to foster a nationalistic art movement with the inherent spiritual value necessary to convey public virtue.22Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1540. With their goal to produce a nationalistic art, managers were skeptical of the emigrants that infiltrated the market with contemporary European works, thus presenting American art with competition that it could not withstand on its own.

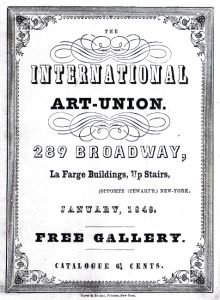

As Goupil, Vibert & Co. witnessed the success of the American Art-Union, they attempted to reproduce a similar service that included European works with the creation of the International Art-Union in 1848.23Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1549. Emulating the American Art-Union, they established a gallery with subscriptions that provided customers with engravings and guaranteed entry into a lottery that gave them a chance to win European and American art works.24Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1549. However, instead of using their profits to support American artists, the company promised to sponsor one American artist to study abroad in Europe for a year, and kept the rest for themselves.25Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1549. As an established commercial gallery, Goupil, Vibert & Co. not only presented a threat to the American Art-Union’s customer base, but also embodied the exact profit-seeking corporation within the art market that did not have American artists in mind. In the Bulletin, a writer suggests that the artists of most French paintings and statues openly engage the viewer with the lewd and salacious, going onto accuse the emigrants of demoralizing America to fulfill the audience’s sensual appetites for profit.26“The International Art-Union,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union, November 1849, p. 12-13. Although the organization held a prominent position by the late 1840s, opposition from the press and artists ultimately resulted in its demise a few years later.

Figure 2. The International Art-Union, exhibition catalogue (New York: Oliver & Brother, 1849), frontispiece.27Nineteenth-century art worldwide. “The Perils and Perks of Trading Art Overseas” (web page), Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide (website), accessed May 6, 2020, https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring17/penot-on-the-perils-and-perks-of-trading-art-overseas-goupils-new-york-branch.

In 1848, owner and editor of The Home Journal—a publication targeted toward middle-class women—Nathaniel Parker Willis engaged in the public debate, defending the French pair as legitimate arbiters of taste in contrast to the ‘merchant amateurs’ that managed the Art-Union.28Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1550. Willis went on to suggest that the Art-Union’s system was inherently flawed, because of its emphasis on inclusivity and inadequate appreciation and compensation for artists.29Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1551. He criticized the organization’s reliance on prizes to increase its distribution, a structural dynamic that he argued compelled the purchasing committee to obtain a large quantity of paintings at a low cost.30Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1551. Due to the Art-Union’s lack of competition and discrimination, Willis accused it of becoming a “guano to mediocrity,” which failed to encourage artists to improve because it championed pictures that would have otherwise gone unsold, as prizes.31Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1551. Klein states that “unlike members of the Art-Union set, who believed that taste could become universal, Willis constructed taste as a form of capital—superior to wealth, limited in supply, and accessible only to the enlightened few.”32Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1550. His opinion was echoed in the International Magazine of Science and Art, in the 1850 article “Art-Unions Considered.”33Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1551. Willis ultimately advocated for the adoption of the European model, which would entail the establishment of public galleries with periodic viewings of private collections made available to the public.34Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1554.

While the Art-Union saw the democratization of taste as crucial to the establishment of a distinctly American art, the Home Journalsided with the National Academy of Design, echoing artists concerns over the Art-Union’s competing model of aesthetic authority.35Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1554. Fearing that artists would opt to sell their work to the Art-Union instead of exhibit it with the National Academy, Academicians blamed the Art-Union’s gallery for their dwindling admissions.36Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1554. However, the most vehement opposition the Art-Union faced was not from the Academicians, but originated in the second and third tiers of artists below them, who relied on the Art-Union to provide a market for their paintings.37Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1554. Landscape artist Thomas Doughty, once a notable artist but later forgotten, published a letter accusing the Art-Union for suddenly discontinuing his patronage after purchasing about fifty of his works from 1839 to 1850.38Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1555. Doughty’s concerns illuminated the organization’s problematic position as a taste maker that had too much control over the American art market, as he argued that the men of the Art-Union were attempting to engage in matters beyond their professional expertise.39Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1555. In response to these issues, by the late 1840s, a group of New York artists joined Willis in constructing alternatives to the current system of American patronage.40Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1555. John Kendrick Fisher, another artist that failed to rise through the ranks of the National Academy, exhibited several paintings with the American Art-Union and sold only one to the organization in 1849. Fisher joined Willis in arguing for the foundation of public galleries in urban cities to house collections and protect artists that lacked sufficient patronage.41Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1556.

Eventually, both Fisher and Doughty published their critiques in TheNew York Herald, a penny-press which emerged as the American Art-Union’s dominant antagonist. By their very nature, penny papers were engaged in an aggressive campaign to expand circulation, constructing themselves as the unbiased critic and voice of the public. In doing so, they avoided explicitly addressing class politics, and instead, represented the public struggle against the privileged Art-Union and the cultural privilege it represented. The Herald praised Goupil and Vibert as it criticized the wealthy Art-Union managers who believed that they could create an institution to imbue the public with a national taste, contending that instead, the organization functioned to promote the private interests of its managers. Despite their common hostility towards the Art-Union, The Home Journal sided with academicians while the penny press gave voice to the American artists that were lacking in institutional privilege. Eventually, the Herald focused in on the Art-Union’s lottery system, suggesting that it allowed the managers—who never provided the prices they paid for paintings—to deceive lottery winners and undercut artists by paying low prices. Although the Art-Union lottery was modelled after licensed lotteries of the eighteenth-century which served to raise money for community projects, Klein suggests that during the antebellum decades “lotteries acquired a new meaning. They evoked concern among reformers who associated recreational gambling with supposed urban sins from laziness to poverty, financial profligacy, and thievery.” The Herald’s ingenious strategy to target the lottery as fundamentally problematic was successful, because it put Art-Union managers in positions of cultural authority where they did not belong. When subscriptions dropped dramatically in autumn of 1851, officials were forced to delay their payment to artists, which fuelled assaults of the organization in local newspapers, as they charged the Art-Union with consistently undervaluing American artists’ work.42Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1556-1559.

Its downfall began in January 1852, when the Art-Union managers sued the Herald’s paper editor James Gordon Bennett for slander. Throughout the case, the penny press portrayed itself as the heroic voice of the public brave enough to challenge those in power. When the court closed the case, Bennett sought revenge by asking the judge to issue an injunction against the Art-Union. Although his proposition was initially declined, with the pressure of the press, Bennett ultimately forced the district attorney to bring two actions against the organization in the Supreme Court. In June of 1852, the court ruled the Art-Union an illegal lottery and, by extension, a violation of the state constitution, bringing an end to the organization after thirteen years. The emergence of the Art-Union, marked a moment when wealthy leaders believed it possible to create and regulate a shared culture. However, its turbulent life was indicative of a public skepticism around the idea that the few could craft a culture for the many. Therefore, instead of providing a foundation for social and national unity, the Art-Union illuminated the class divisions that lay just beneath the surface.43Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1559-1560.

Figure 3. Samuel Wallin, Gallery of the Art-Union, May 1849, print from Bulletin of the American Art-Union.44Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 41.

The Proliferation of Periodicals and the Development of a Public Voice

The Art-Union was ultimately brought down by the public press, which amassed popularity and influence from the mid-century onward. As the prosperous economy of the late 1840s attracted immigrants, Manhattan’s population boomed, increasing from about half a million in 1850 to over 800,000 by 1860.45Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 39. The mid-century also marked the development of the American department store and the beginning of the proliferation of print media for the public. While the Herald was founded in 1835, the New York Tribune followed shortly after in 1841. By the 1850s, theNew York Tribune was the city’s largest daily paper, achieving circulation of approximately 200,000.46Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 39. The New York Times followed shortly after, publishing its first issue in September of 1851. Fine arts periodicals evolved alongside news media, oftentimes supplementing individual galleries and associations, or serving as a platform for artistic critics to broadcast their opinions. Along with the periodicals mentioned above, the Photographic art journal emerged in 1851 and had a nine year run, while both the Illustrated Magazine of Art and Lantern were founded in 1852. The Crayon: A Journal Devoted to the Graphic Arts & the Literature Related to Them,was founded and edited by William Stillman and John Duran in 1855.47Rosetti Archive, “Periodicals” (web page), Rosetti Archive (website), accessed May 6, 2020, http://www.rossettiarchive.org/racs/periodicals.rac.html. A year later, the Cosmopolitan Art Journal was published by the Cosmopolitan Art Association, which attempted to replace the American Art-Union in the mid-fifties, although it did not survive the Civil War.48Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1559. New publications continued to emerge for the remainder of the nineteenth-century, as artistic discourse multiplied in America.

In this age of periodicals, it mattered more than ever to have access to the various perspectives print media provided, especially if one was to cultivate appropriate artistic taste. On February 7, 1852 in Mr. Diogenes’ the Lantern—a short lived satirical journal—published an article titled “Progress of the Fine Arts in America,” written under the pseudonym J. Bull Caulkney, as a letter from an English gentleman travelling through the United States. Beginning in the eighteenth century, John Bull became a national personification of England, especially in political cartoons and other graphic representations. Therefore, the author was not a real person, but instead embodied the cultured country of England as he criticized American art’s prospects in the context of the “barbarous” country’s general lack of refinement. He goes on to speak of the various methods of art viewing available to Americans. After mentioning the “great gallery” of the American Art-Union, he states “the annual lottery of this institution was to have been drawn some time ago; but its plan prohibits more than five dollars (one pound English), being given for any one picture, the managers have wisely determined to postpone the drawing until they have purchased as many pictures as there are subscribers, so that each will be sure of one. This must be admitted to be an extraordinary indication of progress in the arts.” His satirical commentary sarcastically re-enacts Willis and Fisher’s criticism of the American Art-Union and its propensity for mediocrity, before he moves on to belittling the National Academy of Design. In regards to the National Academy, he claims “I have seen nothing of it, to speak of. They say, however, that its intentions are much better than its designs. It is certainly to be hoped so.” With this comment, he disparages the attempts to cultivate an American art in a broader society that lacks the cultural heritage of Europe.49“Progress of the Fine Arts in America,” The Lantern, February 7, 1852, p. 46.

The Crayon espoused Ruskinian tenets of aestheticism, republishing a large amount of John Ruskin’s work to share it with the American public.50Rosetti Archive, “Periodicals” (web page), Rosetti Archive (website), accessed May 6, 2020, http://www.rossettiarchive.org/racs/periodicals.rac.html. The journal begun as a weekly 16-page publication, quickly evolving into a 32-page monthly publication in 1856 that charged just 3 dollars for a yearly subscription.51Rosetti Archive, “Periodicals” (web page), Rosetti Archive (website), accessed May 6, 2020, http://www.rossettiarchive.org/racs/periodicals.rac.html. It has been observed by Frank Luther Mott in his study of American Magazines, as the best art journal of its period, particularly because of its vast scope and convincing authority.52Rosetti Archive, “Periodicals” (web page), Rosetti Archive (website), accessed May 6, 2020, http://www.rossettiarchive.org/racs/periodicals.rac.html. In 1855, The Crayon reviewed the Academy’s 30th annual exhibition, characterizing the display and its rooms as small, although the show offered more choice than previous exhibitions.53“The National Academy of Design,” Crayon March 21, 1855, p. 186. The journal goes on to suggest that despite this “there are still, we think, too many poor portraits and absolutely bad pictures, which neither honor the artists nor delight the public.”54“The National Academy of Design,” Crayon March 21, 1855, p. 186. The article goes onto address the few strong pictures in the exhibition, praising Asher B. Durand’s In the Woods, for its unusually good quality and “almost pre-Raphaelite truth of detail.”55“The National Academy of Design,” Crayon March 21, 1855, p. 186. Durand’s painting was a full-scale, vertically oriented, finished landscape that depicted a slightly cropped and narrow view of a forest glade. The work emphasizes the visual details and minutia of the forest’s interior while unequivocally placing the viewer—manipulating their viewpoint so the foreground matches the spectator’s—in the woods. The clarity and almost scientific specificity mimics a sharp focus which signals the viewer’s proximity to the objects. WhileThe Crayon praised Durand’s exactness, it was not the only publication to address In the Woods. In fact, the painting divided critical opinion across various periodicals.

In “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse. Or, Should Art ‘Deal in Wares the Age Has Need of’?” Karen L. Georgi unpacks the critical reception of landscape painting, employing Durand’s painting as a case study. Although Georgi notes that American art criticism in this moment “cannot well be described as provocative or even particularly accomplished, the rhetorical choices are often instructive.”56Karen L. Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse. Or, Should Art ‘Deal in Wares the Age Has Need of’?” Oxford Art Journal 29 no. 2 (2006): 229. Engaging with Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science, and Art and the New York Times conflicting reviews, she argues that the terms of the debate around landscape painting made nature function as a metaphor, symbolizing the weighty American values—like religion, nationalism, and liberty—that characterized the larger debate over the significance of American landscapes and, by extension, the purpose of American art.57Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 229. The nineteenth-century saw the rise and fall of the first cohesive artistic movement in America, known as the Hudson River School. Lasting approximately half a century from 1830 to 1880, the movement was characterized by naturalistic, picturesque American landscapes.58Angela L Miller “Nature’s Transformations: The Meaning of the Picnic Theme in Nineteenth-Century American Art” Winterthur Portfolio 24 no. 2/3 (Summer-Autumn, 1989): 113. According to critics, a true landscape had to present the viewer with a narrative which, as Georgi suggests, re-enacted man’s relationship with and, ultimately, mastery over nature.59Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 231. The cropped composition and its vertical orientation—lacking in peripheral vision—places the viewer in a chronological narrative. In the strict ordering of the natural world, the successful landscape painter rendered harmony and symmetry in the face of disorder, leveraging narrative form to present a cohesive ideal which recreates man’s imposition of order.60Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 231. In doing so, the artists elevated the value of the art object by leveraging geometric harmony’s association with the divine organizing presence of God.61Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 232. Durand’s steadfast loyalty to rendering the natural world allowed some critics to doubt his use of narrative. However, it was precisely his privileging of naturalism over imagination that characterized this younger generation of artists as they made the genre their own in the midst of a rapidly growing economy.

Georgi centers her argument around the critical disparity in the piece’s reception between the two publications. Although Durand’s paintings were generally well-liked by the press, In the Woods was controversial, polarizing critical opinion depending on how critics interpreted either the importance or insignificance of a painting which dwells on the minute details of the material world. However, as Georgi argues, the very question itself brought other fundamental concerns to light, as critics responded to Durand’s surprising landscape employing the language of class, labour, and materialism. She suggests that the debate centered around whether the painting was a landscape or study, imagination or imitation. Georgi investigates this dichotomy and its relationship to the cultural factors which impacted its critical reception.62Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 235.

As in the Crayon, both reviews began by addressing the Academy’s shortcomings, and the bleaker reality of American art in general.63Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 241. The Putnam’sreviewer goes on to classify Thomas Cole and his imaginative landscapes as outdated, sentimental and un-American.64Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 242. Cole contrasts with Durand’s younger generation of artists and their focus on conveying an expression of the world around them that is simultaneously naturalistic and idealized.65Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 242. Like The Crayon, Putnam’s employed a pictorial vocabulary to find meaning and significance in the purely visual experience, as artists straddled the line between real and ideal.66Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 245. This interpretation argues Durand’s In the Woods was a particularly successful landscape because it privileged the minutiae of nature’s details, suggesting that representation is significant in itself, despite the fact that higher meaning had traditionally been found in the abstract.67Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 244. The New York Times, on the other hand, was far more skeptical, dismissing the work as a mere accumulation of parts.68Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 244. The particularized visual detail renders the depiction completely useless and denies it the status of art by relating it to commodity production, thus refuting art’s object-hood and relationship to materialism.69Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 244. These reviews represent entirely different interpretations of the same aesthetic qualities, displaying polarized opinions surrounding art’s higher meaning and fundamental value.70Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 243. Georgi argues that this is indicative of “a correlation between a populist, self-proclaimed progressive definition of art and a preference for the careful attention to the objects of the material world.”71Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 243. Her article concludes that the discursive attention paid to the natural world was indicative of the anxiety surrounding a rapidly changing society, and specifically, around the rise of consumerism.72Georgi, “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse,” 244. Given that the commodity economy focuses on interpreting surfaces, these details and their materialism become significant in their own right in the democratic Putnam’s publication.

Figure 4. In the Woods, Asher Brown Durand, 1855, oil on canvas, 60 x 48 inches, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Founding the Metropolitan Museum

From 1861 to 1865, the Civil War provided a thriving market for American art, but by the war’s end, American artists were already reinventing themselves. In 1863, a group of young artists formed the first self-conscious “school” of artists, naming themselves the Association for the Advancement of Truth in Art. The group labelled themselves American Ruskinians, and immediately founded The New Path, a monthly art journal that condemned prominent American painters as formalists who believed they were painting nature, but were in fact, just rendering outdated pictorial conventions. Its editor Clarence Cook was a Harvard graduate in architecture, who later emerged one of the most significant commentators of his generation once he was named art critic of the New York Tribune in 1864. He held his position at the Tribune until 1883, when he took over The Studio, an illustrated monthly journal devoted to the fine arts. Cook moved beyond his Ruskinian insistence on capturing the minutia of nature at the end of the 1860s, but he continued to criticize mainstream American artists as provincial in their failure to compare to European contemporary art’s innovation.73Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 45.

In June of 1867, the Tribune—presumably Clarence Cook—was reviled by the poverty of the 41stannual exhibition at the Academy. He finds fault in the exhibition’s inclusivity, arguing that it would be impossible for all six hundred works in one particular show in France to be good, let alone in America, “where there is no experience in Art worth mentioning, where there are no traditions, where there is no proper training.”74“The National Academy of Design,” The New York Tribune, June 14, 1867, p. 2. However, he argues that there is no alternative to exhibiting so many pictures, because there are no reliable judges that might decide which to include, and the show would be so small that “it would be hardly worthwhile to have erected the Academy Building to hold it.”75“The National Academy of Design,” The New York Tribune, June 14, 1867, p. 2. While the older artists built up the Academy—doing their best to advance art in a moment when the general public was disinterested and technical ability was rare—Cook claims that the American public will have to wait a few more years, as more students study high art, and effective teachers disseminate artistic knowledge into a broader system of education, before American art might mature into a lineage comparable to Europe’s.76“The National Academy of Design,” The New York Tribune, June 14, 1867, p. 2. Kenneth Meyers suggests that Cook’s criticism brought with it a new cosmopolitanism that aided the transformation of New York’s art world in the decades after the Civil War.77Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 45. However, the sixties also saw the advent of Watson’s Weekly Art Journal, The Aldine: A Typographic Art Journal, and Appleton’s Journal, each of which expanded artistic discourse in New York City.

In the same year, the Universal Exposition in Paris drew a substantial group of New York’s prominent collectors of American art, who—following their works across the Atlantic—were exposed to leading European artists. They returned home, eager to learn more about and acquire art from abroad. The sale of European art boomed throughout the seventies in New York, meaning the rapid expansion of commercialized galleries specializing in the sale of European art. Concurrently, American artists and collectors flocked to Europe, promoting transatlantic communication that manifested in the popular American impressionist movement. While some American artists lobbied for protectionary measures like increased tariffs in the midst of the growing demand for European art, Cook, along with other leading critics and journalists, argued that American art was desperately in need of this competition.78Kenneth J. Meyers, “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914,” in Rave Reviews ed. David B. Dearinger (New York: National Academy of Design, 2000), 45.

It was in this context that John Jay, wealthy lawyer and financier, as well as a noted proponent of the Art-Union, initiated the establishment of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The first meeting, which was held by New York’s Union League Club in 1869, hosted four men who had previously been American Art-Union managers. It also included William Cullen Bryant, an American poet and journalist that urged the gentlemen to promote art’s “wholesome, ennobling, instructive” influence in the face of the “temptations to vice in this great and too rapidly growing capital.” Although the museum emphasized its role in educating the public, its intended audience was far smaller than the American Art-Union’s. In fact, they made the museum less accessible to the working classes by limiting evening hours and free admission to specific days, alongside implementing unspoken rules of decorum around spectatorship. The museum was constructed with the use of trustees, who relied on a broad range of funding—including donations, governmental allowances and fees—as opposed to public subscriptions. Trustees controlled the contents of the galleries, filling the museum with art purchases from around the world, alongside the donations it received from well-off art collectors. In abandoning the direct patronage of American art and introducing barriers to entry, the MET advertised itself as a preserve of excellence available only to the enlightened few.79Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City,” 1560.

Professionalizing the Woman Artist

Founded in 1859 by self-educated industrialist Peter Cooper, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art made artistic education available to women. Quickly after it was established, Cooper Union offered a broad selection of daytime art classes for women. In the same year, three drawings by “Pupils of the New York School of Design for Women, Cooper Institute” were exhibited in the National Academy. The Academy openly supported female participation and professionalization in art, and its inclusive exhibition policy meant that artists of diverse skillsets, identities, and backgrounds were showcased alongside one another. In fact, the National Academy judges accepted almost every painting submitted to its annual exhibition until at least 1860. The Crayon highlighted its democratic hanging policy in a review of the 35th annual exhibition, stating “no exhibition in the world—certainly not in Europe—is hung with the same consideration for the rights of all.” In 1867, the National Academy even opened its galleries to host exhibitions by the Ladies’ Art Association. As American artists travelled to study abroad in Europe in the 1870s, ambitious middle-class ladies flocked to art schools in America and Europe, marking a moment in history in which women were finally given the opportunity to engage in an artistic education comparable to men. This combination of education and institutional exhibition venues allowed for their artistic success.80April F. Masten, Art Work: Women Artists and Democracy in mid-Nineteenth Century New York, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 13.

Women made the most of their opportunities, employing their art to reinforce proper American values and standards of refinement, while simultaneously subverting stereotypes of domesticity by having a public facing career. Kirsten Swinth’s Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870-1930, investigates the professionalization of women artists in this period, examining the records of successful women artists that were associated with New York Arts Students League, Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts School. While the National Academy group exhibitions provided a more inclusive space for women to exhibit their work, women still faced discrimination and significant obstacles to fame. They often turned to less prestigious media such as water colors or home decoration in the face of male competition that dominated the realm of “high art.” In At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America, art historian Laura Prieto argues that, for these reasons, women and men had vastly different artistic networks. Over two chapters, Prieto charts the emergence of the lady amateur ideal in antebellum America, which served to both help and hurt women in attaining their status as professional artists later on in the century.81Karen J. Blair, “Reviews of Books: Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870-1930 by Kirsten Swinth; At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America by Laura R. Prieto,” The American Historical Review 107 no. 5 (2002): 1571-1572.

Although women became a permanent part of the Academy schools after the Civil War, few of them received regular critical attention in the press.82Masten, Art Work, 16. With the public’s interest in foreign art, the demand for American art bottomed out in the 1880s, paralleling the demise of landscape painting. At this moment, the Academy came under siege by progressive artists and critics who opposed its inclusive nature. As the annual exhibitions became less popular throughout the decade, the list of alternative artistic venues at the back of the National Academy Notes pamphlets grows in length. Titled “Art Attractions of New York,” the 1889 section recommends the Metropolitan Museum of Art as the most interesting permanent exhibition in the city, and then it goes on to list various libraries, societies, clubs, churches, and associations that display art.83Charles Kurtz, National Academy Notes no. 9, 1889. The proliferation of various artistic associations served to further divide artistic networks on the basis of gender, excluding women and their art from more selective and elite exhibition spaces that might raise their value.84Blair, “Reviews of Books,” 1571. Despite this, the US Census of 1890 counted female participation in the arts—as artists, sculptors, and art teachers—at a peak 48%.85Blair, “Reviews of Books,” 1571. While the Academy provided spaces for women, dealers served as gatekeepers—which embodied the crucial function to curate taste—and along with the new artistic associations, they served to marginalize women in the art market.86Blair, “Reviews of Books,” 1571.

The Triumph of the Commercial Gallery and the Rise of Modernism

The repudiation of the National Academy of Design paralleled the critical defeminisation of art in the press. The institutional failure to craft a successful national art was indicative of the public’s general distrust in American refinement and cultural taste, in the face of European competition. Swinth suggests that Theodore Roosevelt’s election in 1901 marked a turning point for the development of a virile modernism to match his vigor going into the twentieth century.

Art critics rejected the idea of art for refinement as feminine, low-brow, and mere entertainment. In its place, they called for a bold style of self-expression and individuality that became closely entangled with a masculine ethos. Swinth labels this shift as anti-democratic, arguing that it was unconcerned with unifying classes and hostile to mass-consumption, serving to reinforce elitist taste as a form of limited capital. Despite the efforts of various institutions, it is evident that this ideology set the stage for the rich art market characteristic of twentieth-century New York, a century in which the sale of art became increasingly associated with luxury and desire.87Blair, “Reviews of Books,” 1571.

Author: Mackenzie Philbrick

Date Written: May 8, 2020

Primary Sources

The New York Tribune archive

Bulletin of the American Art-Union

The International Monthly Magazine of Literature, Science & Art

National Academy Notes

The Lantern

The Crayon: A Journal Devoted to the Graphic Arts & the Literature Related to Them

Secondary Sources

Blair, Karen J. “Reviews of Books: Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870-1930 by Kirsten Swinth; At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America by Laura R. Prieto.” The American Historical Review 107 no. 5 (2002): 1571-1572.

Georgi, Karen L. “Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse. Or, Should Art ‘Deal in Wares the Age Has Need of’?” Oxford Art Journal 29 no. 2 (2006): 227+229-245.

Klein, Rachel N. “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City: The Rise and Fall of the American Art-Union.” The Journal of American History, 81, no. 4 (March 1995): 1534-1561.

Masten, April F. Art Work: Women Artists and Democracy in mid-Nineteenth Century New York. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Meyers, Kenneth John. “The Public Display of Art in New York City, 1664-1914.” In Rave Reviews edited by David B. Dearinger. New York: National Academy of Design, 2000, 31-51.

Miller, Angela L. “Nature’s Transformations: The Meaning of the Picnic Theme in Nineteenth-Century American Art.” Winterthur Portfolio 24 no. 2/3 (Summer-Autumn, 1989): 113-138.

Rosetti Archive. “Periodicals” (web page). Rosetti Archive (website). Accessed May 6, 2020. http://www.rossettiarchive.org/racs/periodicals.rac.html.