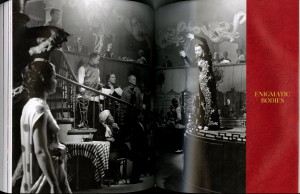

Scene: Yimou, Hero (2003).

Zhang Yimou’s film Hero tells the story of Nameless, a warrior who attempts, with the help of three assassins, to kill the King. As the story unfolds, the king unravels Nameless’ plot piece by piece in increasing detail. There are three main phases of the film characterized by three different colors. The first phase is characterized by red, it is a story of betrayal specifically between the assassins Flying Snow and Broken Sword that leads to Nameless defeating the assassins, this part of the story happens to be untrue. The second phase, characterized by blue scenes and costumes, tells the story of love and sacrifice between Flying Snow and Broken Sword, however, still presumes that Nameless is attempting to defeat the two assassins to save the King. The final phase of the story is characterized by white and tells the true story of how Flying Snow and Broken Sword sacrifice themselves to give Nameless the opportunity to assassinate the King. The Scene depicted above is part of the blue phase, it shows a fight on the water between Broken Sword and Nameless while Flying Snow lies dead. In this scene the color blue, present in the surroundings and the costumes acts as a narrative bridge between the radical lie that Nameless tells the king and the whole truth of the plot to assassinate the king.

The fight takes place on the lake itself, with a dance like quality to the movement over the surface of the lake. The entire scene takes place in a blue surroundings, which stands in stark contrast to the red forest in the first part of the story and the white surroundings, specifically the desert, in the last scene. If we consider the symbolism of the blue surroundings (the lake) we can consider that it acts as a bridge between the lush forest, often a symbol of life, and the stark desert, often a symbol of death. The blue tones of the scene are carried through the water and symbolize the partial truth of the story that Nameless presents to the king in the blue phase.

The blue of Flying Snow and Broken Sword’s costumes further bridges the narrative between the initial lie that Nameless tells and the final truth about the plot to assassinate the king associated with the white costumes. More specifically, Flying Snow and Broken Sword share a similar blue hue while Nameless is portrayed in a black costume. This highlights the notion that at this moment in the plot, the viewer and the king understand that Flying Snow and Broken sword, in their commitment to each other, are willing to sacrifice their lives to fulfill a greater goal. However, the narrative has not yet revealed that Nameless too is part of the plot to assassinate the king. In this scene his black costume, in contrast to the blue background and costumes, portrays Nameless as the outsider or opposing force to Flying Snow and Broken Sword’s plan to assassinate the king. Eventually Nameless adopts a blue costume and begins to reveal his intentions to unify with the three other assassins in order to kill the king. In this way the colors and costumes of this scene serve as a bridge between the fragmentation between characters, specifically Nameless from the three assassins and Broken Sword and Flying Snow from each other and the unification at the end of the narrative not only between the three assassins but of all of China under one king.

clear and persuasive

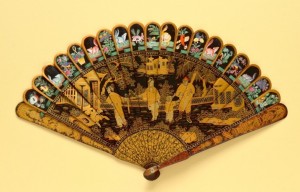

Brise fan made in France c. 1830 – 1840

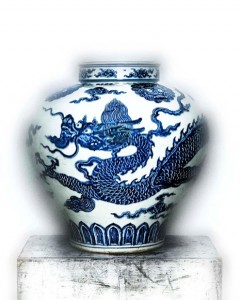

Brise fan made in France c. 1830 – 1840 Jar with Dragon. Early 15th Century.

Jar with Dragon. Early 15th Century.