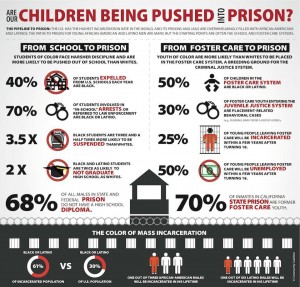

“Teacher Education and African American Males: Deconstructing Pathways from the Schoolhouse to the ‘Big House’” (“TE”)20 and “Welcome to a Special Issue About the School-to-Prison-Pipeline: The Pathway to Modern Institutionalization” (“SI”)21 both discuss the school-to-prison-pipeline as it stands today, its creation, and those who are involved.

In “TE”, Brenda Walker focuses on African American males and their statistical tendency to struggle in school and be incarcerated more often than other social groups. She then identifies several of the common practices in schools that create this pipeline in which “less than half of African American males actually graduate from high school with their cohorts.”(320) One of these practices is grade-level retention, or when students are forced to repeat a grade due to

academic failure. A 2002 study found that “27% of 10th-grade African American males had been retained at least once… In comparison, 18% of the Hispanic students and 13% of the white students were retained once.”(321) Another harmful practice concerns common disciplinary policies as African American males are “suspended 2.6 times more frequently than white males.”(322) In addition, African American males are disproportionately placed in juvenile detention centers, particularly when the issue revolves around drug offenses, in which “African Americans are detained 7 times more often than their white peers.”(323) These are the “exclusionary school and societal practices” that make up the school-to-prison-pipeline for African American males.

More facts about who is in the school-to-prison pipeline.

David Houchins and Margaret Shippen, authors of “SI”, agree with the idea that exclusionary practices promote the school-to-prison-pipeline, but widen the arena of societal groups who feel the effects of these practices. Discussing the 93,000 youth who are incarcerated every day, the authors discuss the commonalities amongst these youth rather than the direct pathways that land them in juvenile justice facilities. Importantly, more than 40% of these youth have disabilities, compared to the 12% of youth with disabilities in public schools. Many of the youth in these facilities have emotional/behavioral disorders or learning disabilities. Disproportionately, “the rate of youth with emotional/behavioral disorders is six times greater in juvenile justice facilities as compared with public schools.”(266) In addition to these common factors, many incarcerated youth have mental health problems. One study “estimated that 60% of youth in juvenile justice facilities exhibit three or more comorbid mental conditions.”(266) These conditions include, but are not limited to, depression, anxiety, and conduct disorders. “SI” also contains information on the disproportionate number of minorities in the pipeline, including African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. The article focuses on African American (lining up with “TE”) and Latino youth who are especially incarcerated a disproportionate amount. Finally, the authors address issue that many youth in the pipeline are impoverished and that poverty “correlates with multiple negative life outcomes, including decreased educational achievement, family dysfunction, and school dropout.”(267)

These two articles paint a picture of the school-to-prison-pipeline that currently exists amongst the youth of our nation. By understanding the factors that help create the pipeline, who these factors affect, and who is caught in the pipeline, we can more readily prepare for the pipeline’s dismantling.

Img:

21