Youth activism is especially important in light of the civic knowledge gap, but it is an issue often under the radar in current ed-reform discussions. This issue, however, is highlighted in both “Prepare students to be citizens” 1 and “Closing the civic engagement gap: The potential of action civics.” 2

The two practitioner-oriented articles point out the lack of attention paid to this civic knowledge gap and resulting civic empowerment gap between middle- and upper-class Whites and low-income minorities. Pope et al. notes that “compared to Americans earning under $15k, Americans earning over $75k are twice as likely to contact an elected official and protest, almost 3 times more likely to participate in informal community activities, and more than 4 times more likely to work on a campaign or serve on a board” (Pope et al. 2011). This gap is alarming, as it threatens the very foundations of our country: a democracy based on a promise of civic equality. The gap means that the most marginalized youth are the least prepared to participate in our democracy. Levinson emphasizes this, as she asserts that “we betray democracy when some individuals or groups find themselves excluded from the halls of power while others easily slip inside.” All-American principles such as “All are equal before the law” and “One person, one vote” are empty statements unless all Americans are able to have a voice. The inattention paid to this issue is bewildering considering the significance of a civic knowledge gap.

To underscore the extent of the civic knowledge gap, Levinson compares it to the academic achievement gap, stating that it is just “as large and as disturbing” (Levinson 2012). It is interesting, then, as Pope et al. explain, that this gap is likely a result of the focus on literacy and math in school curriculum. While civics used to be studied in public schools, in recent years it has been ignored due to a preference for standardized tests and the value placed on competition for economic success in a global economy. While both gaps are reason for concern, it is absurd that one is receiving little limelight though both are equally heavy matters. Levinson questions the logic that schools offer math and reading every single year, but offer civics courses a few times (at the max) throughout schooling—and then, expect students to become a responsible and engaged citizen. It really makes no sense at all!

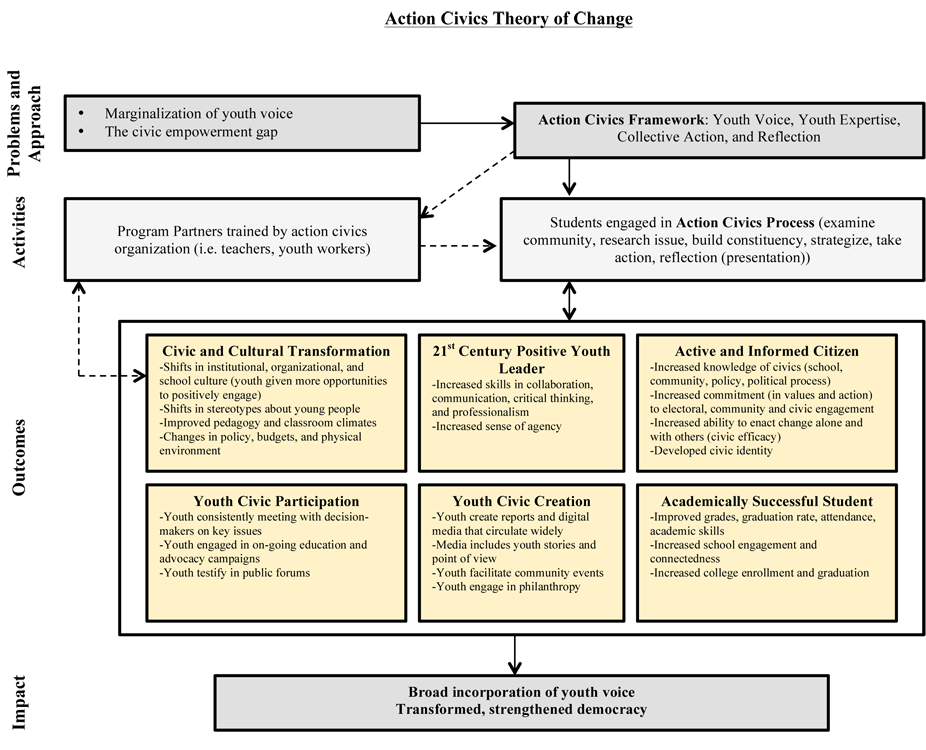

The two articles recommend that organizations and schools adopt the “action civics” approach, with its more engaging, active, hands-on, and youth-oriented pedagogy than old school flow charts and worksheets handed out in civics classes. This is an excellent approach that ought to be adopted by adult facilitators in youth organizations searching for a model to guide youth in becoming activists.

ACTION CIVICS PROCESS

3

4

Considering the correlation between the achievement gap and the civic knowledge gap, as well as the focus on high-stakes testing in Boston Public Schools which pushes out civics education, these youth activism groups in Boston are even more vital. Luckily, the nature of cities can be taken advantage of, as the large population and close social interactions of urban areas offer promise of possible coalitions and teamwork that may help fuel success for youth campaigns. I believe that a combination of civic knowledge as well as social capital enables wealthier White citizens to have more political power than low-income minorities. Youth organizations, however, provide both of these resources to low-income youth in the city, in that they 1) educate youth on relevant social justice issues and how to challenge them and they 2) foster relationships with adult mentors and peer youth activists, thereby expanding their social networks and building social capital. In such a way, youth activism grassroots organizations offer a solution to closing the civics knowledge gap among Boston youth.

Sources

1. Levinson, Meira. 2012. Prepare students to be citizens. Phi Delta Kappa, 93, 66-69. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/963952761?accountid=9681.

2. Pope, A., Stolte, L., & Cohen, A.K. (2011). Closing the civic engagement gap: The potential of action civics. Social Education, 75, 267-270. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/education/docview/903703356/549870AF1A434B09PQ/1?accountid=9681

3. Action Civics Process [Digital Image]. (2014). Retrieved from http://actioncivicscollaborative.org/why-action-civics/framework/

4. Action Civics Theory of Change [Digital Image]. (2014). Retrieved from http://actioncivicscollaborative.org/why-action-civics/theory-of-change/