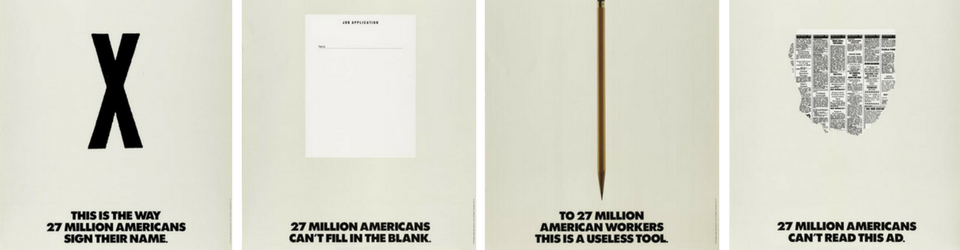

A student’s academic success depends not only on the quality of that student’s school, but also on that student’s home environment. Significant learning takes place before students so much as set foot in a classroom, and this early learning can influence a student for the rest of their academic career. In fact, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), “Children who have not developed basic literacy skill by the time they enter school are 3 to 4 times more likely to drop out of school” (as cited in Kim & Byington, 2016, p. 1).

Critical to a child’s early literacy development, as well as to their later success in school, is their parent or caregiver’s literacy. The NCES finds that “a mother’s literacy level is a significant predictor of a child’s future success in school” (as cited in Kim & Byington, 2016, p. 1). Therefore, when seeking to improve students’ academic outcomes, it is critical not only to support students themselves, but also to support their adult parents and/or caregivers who may need assistance in developing their own literacy.

Adults are engaged in literacy education primarily through adult literacy classes or family literacy programs. Though the former focuses solely on the adult and the latter primarily on the child, both ultimately serve to develop the adult’s literacy skills.

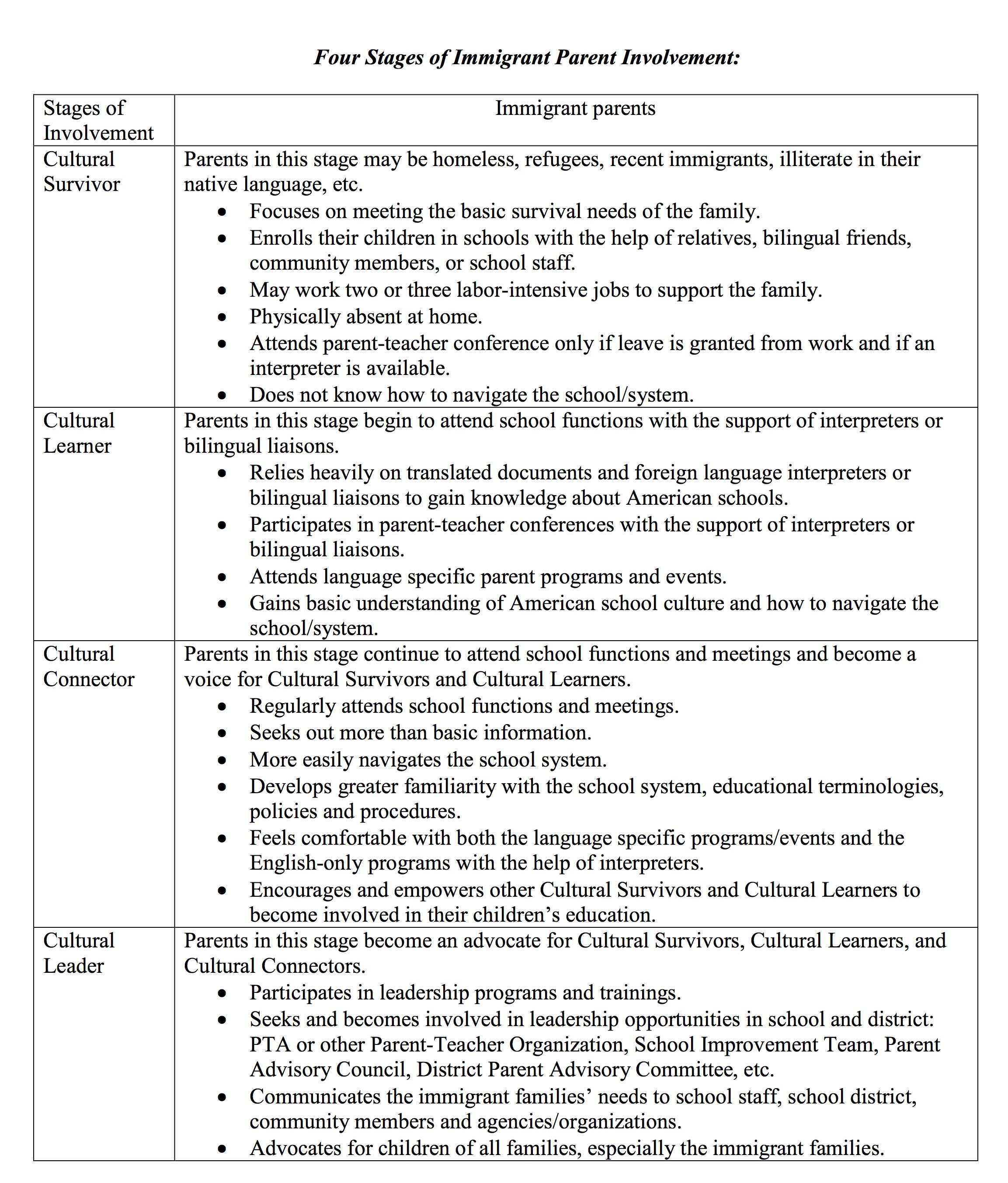

In their research, Han and Love focus specifically on the involvement of immigrant parents in their children’s education. Of course, immigrant parents come from a diversity of backgrounds themselves. For example, while some may be illiterate, others move to the U.S. having earned the equivalent of a PhD in their native countries (Han & Love, 2015, p. 22). These differing experiences and abilities influence the role that immigrant parents can play in their children’s educational careers. Han and Love argue that the school community must “understand who these families are, their needs, and how schools can bridge the linguistic and cultural gaps between homes and schools” to successfully engage immigrant parents as partners in their children’s education (Han & Love, 2015, p. 22).

Immigrant parent involvement can be understood through the four stages that Han identifies in her earlier research. (Fig. 1)

Han, Y. (2012). Four Stages of Immigrant Parent Involvement [Reprinted from “From Survivors to Leaders: Stages of Immigrant Parent Involvement in Schools”]. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

Literacy is a crucial component of an immigrant parent’s movement through these four stages. To progress from a Cultural Survivor to a Cultural Learner, for example, one must gain literacy at least in their native language so as to be able to review translated documents. Progression to a Cultural Connector or a Cultural Leader requires at least basic proficiency in English, so as to be able to share information with and advocate for the Cultural Survivors and Cultural Learners within the community.

Understanding Han’s model allows “schools and districts [to] develop programs and services not only to meet the basic needs of immigrant parents but also to equip and empower parents to become leaders in their school community,” which is promising for the development of grassroots literacy organizations (Han & Love, 2015, p. 23).

Kim & Byington build on Han and Love’s work by examining how the duration of programs and individual family characteristics affect the efficacy of literacy programs. Conducting research in “economically disadvantaged areas in an urban area of a southwestern state” they found that family literacy programs are efficacious in improving family and child reading and literacy practices, with the greatest effects on “parent’s engagement in language and literacy activities” among families in lower income brackets, for both the 4-week and 6-week duration programs (Kim and Byington, 2016, p. 3, 7). Though Kim & Byington (2016) studied family literacy programs, “one of the objectives of this grant project was to give parents/caregivers more opportunities to practice English”—thus, this program can be considered an adult literacy initiative as well (p. 2). Unfortunately, due to the homogenous population (majority Hispanic, non-native English speakers) small size and self-reported nature of their study, Kim & Byington warn that generalization from their results is limited. That said, the measurable impact of family and adult literacy programs on low-income adult learners is promising for adults learners in general and especially those belonging to immigrant populations.

References:

Han, Y., & Love, J. (2015). Stages of immigrant parent involvement — survivors to leaders. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(4), 21-25. doi:10.1177/0031721715619913

Kim, Y., & Byington, T. (2016). Community-Based Family Literacy Program: Comparing Different Durations and Family Characteristics. Child Development Research, 2016, 1-10. doi:10.1155/2016/4593167