(1)

These peer-reviewed articles establish that trauma is most prevalent amongst adolescents, particularly those of racial/ethnic minorities, and that they need a nurturing environment to cope. They propose that schools should function as such an environment and promote resiliency based approaches as an effective treatment style.

In their article, Screening for Trauma in Early Adolescence: Findings from a Diverse School District, Woodbridge et al. (2015) first establish that exposure to trauma is most prevalent during adolescence and that it is associated with a number of adverse outcomes. Some adolescents experience post-traumatic stress disorder, but research has found that even at subthreshold levels traumatic stress can result in physical illness, impairment of cognitive abilities, developmental disturbances, and psychoeducational behavior problems (Woodbridge et al., 2015).1

Considering the major impact of trauma events at this age, Woodbridge et al. (2015) aimed to determine the prevalence of trauma exposure and traumatic stress in middle school students across different demographic categories in an urban northern California school district. Measuring with self-report surveys, Woodbridge et al. (2015) found that students had experienced an average of three trauma events and that male, Black, Native American, and Latino students reported greater exposure to trauma than female, White, or Asian students. Likewise, African Americans subjects reported more frequent occurrence of the negative symptoms associated with trauma (Woodbridge et al., 2015). Clearly, experiencing and coping with trauma events in youth has racial consequences. Lastly, the trauma events threat of physical assault and separation from a caregiver, were most closely associated with traumatic stress, suggesting that trauma is more toxic when students lack a nurturing environment. Thus, Woodbrige et al. (2015) conclude by emphasizing the importance of screening and treating for trauma in school.1

But what is the best way to accomplish this in schools? In STAIR-A for Girls: A Pilot Study of a Skills-Based Group for Traumatized Youth in an Urban School Setting, Gudiño, Leonard and Cloture (2016) provide a starting place for considering this question.

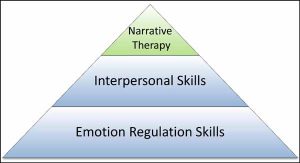

Gudiño, Leonard and Cloture (2016) first establish that adolescents, especially those that are urban, of a racial/ethnic minority, and female, are at a higher risk of experiencing trauma. They then go on to to explain a problematic, cyclical relationship that undermines recovery from trauma (Gudiño et al., 2016). Possessing emotional-regulation skills, strong interpersonal relationships, and an internal locus of control (a belief that outcomes depend on one’s own actions or characteristics as opposed to those outside of their control) helps this population to cope with trauma events. Yet exposure to trauma hinders these very social and emotional skills (Gudiño et al., 2016).2

Some of the skills taught in STAIR (2)

In their study, Gudiño et al. (2016) examined how a strength-based trauma treatment (which they adapted to be suitable for adolescents), Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR-A), that aims to develop these emotional and social competencies, impacted the psychopathology and resiliency of female adolescents in New York City schools. They measured the psychopathology and resiliency of their subjects before and after with self-report questionnaires (Gudiño et al., 2016). They split their subjects into an assessment-only condition (control) and a treatment condition, which underwent a semester long (sixteen-week) intervention that involved personal goal setting, lessons on emotional regulation and interpersonal relationships, role-playing, group discussion, and the creation of written trauma-based narratives. Therapists read and responded in writing to students’ narratives (Gudiño et al., 2016).2

Gudiño et al. (2016) found that participants in STAIR-A showed lower symptoms of psychopathology and improvement in signs of resiliency. Following the intervention, students in this treatment group had better perceptions of social engagement, locus of control, somewhat improved interpersonal relationships, and fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety (Gudiño et al., 2016).2

Gudiño et al’s (2016) research is strong evidence that more schools should consider implementing a resiliency based approach.2

- Woodbridge, M.W., Sumi, W.C., Thornton, S.P., Fabrikant, N., Rouspil, K.M., Langley, A.K., & Kataoka, S.H. (2015). Screening for trauma in early adolescence: Findings from a diverse school district. School Mental Health 8, 89-105.

- Gudiño, O.G., Leonard, S. & Cloitre, M. (2016). STAIR-A for girls: A pilot study of a skills-based group for traumatized youth in an urban school setting. Journal of Childhood and Adolescent Trauma, 9(1), 67-79.

Images:

- Effects of psychological trauma on children and adolescents [photograph]. (2015, December 9). Retrieved April 27, 2017 from https://www.haikudeck.com/effects-of-psychological-trauma-on-children-and-adolescents-uncategorized-presentation-SLejf4gvHs

- STAIR Narrative: A skills focused approach to trauma-related distress [graphic]. (2015) Retrieved April 27, 2017 from http://www.eurekaselect.com/132501