(1)

These practitioner articles argue that since responses to trauma influence student behavior and performance in school, teachers and schools need to institute small practices and larger structural changes that cultivate “trauma-sensitive” schools.

In their article, Trauma and Learning in America’s Classrooms, Terassi and Crain de Galarce (2017) first establish that trauma, particularly complex trauma (prolonged or recurring traumatic experiences), impacts students’ ability to learn. While teachers often misinterpret post-traumatic behavior as misbehavior, trauma neurobiologically alters the brain, impacting physical health and cognitive abilities. After a trauma event, students may be reluctant to trust, act hyper-vigilant, experience increased depression and anxiety, withdraw, or act out (Terassi & Crain de Galarce, 2017).1

Schools and teachers should take advantage of children’s neuroplasticity by creating environments that undo the trauma: “trauma-sensitive schools” (Terassi & Crain de Galarce, 2017). Teachers can foster such an atmosphere by considering a students’ broader context when he or she acts out. Further, they should promote resiliency in the classroom, teaching social and emotional skills, creating predictable routines and clear behavioral expectations, setting up quiet spaces to which students can retreat, and providing sensory tools like fidget toys. These practices can benefit all students, not just victims of trauma. But teachers may find themselves managing a tricky balancing act. Where does a teacher’s job end and a mental health counselor’s begin? How much time can a teacher devote to a single student? (Terassi & Crain de Galarce, 2017).1

Schools should help teachers navigate these challenges. There should be a consistent strategy for supporting traumatized students across the school (Terassi & Crain de Galarce, 2017). There is no one-size-fits-all approach to creating a trauma-sensitive school, but rather, schools must make choices about trauma-related professional development, family engagement tactics, the role of district leadership, and the most effective classroom strategies (Terassi & Crain de Galarce, 2017).1

In her article, At an L.A. School, Carving Safe Spaces to Share and Learn, Evie Blad (2015) describes choices being made in California to create trauma-sensitive schools.

Districts organized under the California Office for Reforming Education are introducing a new measure to their accountability system: school climate (Blad, 2015). It will be measured with surveys gauging how safe students, parents, and teachers feel, suspension rates, and students’ social and emotional skills. This school climate measure will determine 40% of a school’s score (Blad, 2015).2

Blad describes the situation at Florence Griffith Joyner Elementary School in Los Angeles to exemplify the need for this accountability measure and the ways in which teachers are responding to it (Blad, 2015). The school is situated in a poor area, replete with gangs, gun-violence, and homelessness. Just before the article was published, they were mourning the loss of a sixteen-year-old boy to gun violence. Students, then, are exposed to trauma events in their daily lives, which often manifest in student misbehavior and disengagement in the classroom (Blad, 2015).2

“Talking pieces” and the restorative circle (2)

In response, teachers at Joyner are moving away from usual forms of discipline in an attempt to create a supportive, communal environment (Blad, 2015). For instance, teachers facilitate restorative circles, periods during the academic day when students prompt each other to breathe deeply, speak about their lives, and feel the love of their classmates and teachers. Each student brings a “talking piece,” an object or toy that is important to them, and passes it around the circle as they speak. Such a practice creates a space where students feel comfortable sharing openly about their trauma experiences (Blad, 2015).2

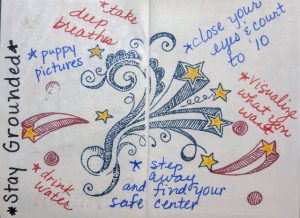

Example of a “Power Plan” at Kansas City Schools (3)

This tactic may not be effective in every setting. Other schools are using other strategies to build this same kind of empathy and support that is characteristic of trauma-sensitive schools (Robertson, 2014). For instance, in Kansas City, at Garfield Elementary and Rogers Elementary, students and teachers write “Power Plans,” lists of their stresses, anxieties, and strategies and affirmations that will calm them when they are distressed. They keep these plans nearby throughout the day and look to them when they need support (Robertson, 2014).3

- Terassi, S. & Crain de Galarce, P. (2017, March 1). Trauma and learning in America’s classrooms. Phi Delta Kappan, 98(6), 35-41.

- Blad, E. (2015, December 30). At an L.A. school, carving safe spaces to share and learn. Education Week. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2016/01/07/at-an-la-school-carving-safe-spaces.html

- Robertson, J. (2014, October, 23). Trauma-sensitive schools in Kansas City want to teach communities to persevere. The Kansas City Star. Retrieved from http://www.kansascity.com/news/local/article3332913.html

Images:

- Trauma safe youth. (n.d). Retrieved April 28, 2107 from http://traumasafeyouth.weebly.com

- At an L.A. school, carving safe spaces to share and learn [photograph]. (2015, December 30). Retrieved April 27, 2017 from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2016/01/07/at-an-la-school-carving-safe-spaces.html

- Trauma-sensitive schools in Kansas City want to teach communities to persevere [photograph]. (2014, October, 23). Retrieved April 27, 2017 from http://www.kansascity.com/news/local/article3332913.html