Neighborhood gun violence drastically affects the lives of students in Chicago, creating a world where students are forced to navigate between funerals and football games. The articles discussed below were written to advise teachers working in schools affected by this violence. Gregory Michie, a 7th and 8th grade teacher at Seward Elementary in Chicago, discusses the effects of gun violence in his classroom in his article from ReThinking Schools titled “Unfolding Hope In A Chicago School.” Micere Keels, an Associate Professor in Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago, published an article in Edutopia titled “Supporting Students With Chronic Trauma,” which gave teachers de-escalation strategies to prevent significant emotional outbursts by students.

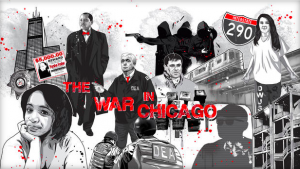

Chicago neighborhoods are plagued by violence; when Keels (2018) wrote her article on March 23, 2018 there had already been “more than 430 shootings and 95 homicides in Chicago” (para. 2). This pervasive violence finds its way into the personal lives of teachers, students, and their families. In early 2016, Mr. Michie (2017) experienced the unimaginable: one of his homeroom students was shot and killed (para. 9). In dealing with the aftermath of the fatal shooting, Mr. Michie (2017) and his colleagues allowed students to spend the morning of the day after in the hallway, hugging, crying, grieving, and talking (para. 14). Allowing students the space to grieve was important and necessary.

Children subject to violence experience adverse effects ranging from those which impact the brain to “hyperactive — unable to contain anxious energy — or hypoactive — unable to muster energy to engage” (Keels, 2018, para. 3) behavior. Despite the existence of such effects of trauma, Mr. Michie (2017) explains that “young people are resilient” (para. 21) and can still miraculously get back to learning soon after traumatic events occur.

Source: Keels, 2018

While students are strong, the adverse effects of violence persist, causing emotional instability and behavioral issues in the classroom. From her research, Keels encourages teachers to learn to recognize triggers for emotional outbursts and build de-escalation strategies. Keels’ (2018) de-escalation strategies are as follows:

- “Avoid ultimatums” and “move the conversation forward” (para. 15);

- “Recap what your student says throughout the conversation…[and] ask if they agree with how you interpreted it” (para. 16); and

- Give your student “a quiet place [to do] de-stressing activities, like drawing or coloring.” (para. 17)

Seeing beyond the violence and towards a peaceful school environment, where all students are supported, is crucial. Mr. Michie (2017) says, “The only real way forward, it seems, is to trudge through the losses and pain hand in hand” (para. 31). Michie’s emphasis on the importance of community, the importance of supporting colleagues and friends, is integral when navigating a school environment subject to violent crime. Further, teachers tackling students’ adverse behavioral effects with “support rather than punishment” (Keels, 2018, para. 21) helps create trust and feelings of safety in the classroom.

Hope is a difficult concept, it is something students and teachers have in schools like Mr. Michie’s, but may sadly never see the results of. However, a school with a strong community and a staff knowledgeable on how to interact with emotionally distraught students can, according to these two articles, allow hope to unfold.

Learn more about Mr. Michie’s experience and opinions on his twitter page @GregoryMichie