On the professional level, discussion of handling trauma in schools is commonplace. The teacher-oriented magazine Curriculum Review published one short informative graphic aiming to educate teachers on the basics of trauma sensitivity in the classroom. This graphic drew information from the sources traumaawareness.com, the Obama White House Archives, and childmind.org. From another teacher-oriented magazine Leadership, Shawn Nealy-Oparah and Tovi C. Scruggs-Hussein, colleagues at Partners in School Innovation, an educational reform non-profit in San Francisco, and adjunct professors at Mills College published an article on recognizing and responding to trauma in students.

The Emotional and Physical Effects of Trauma

Response to trauma can be observed on both an emotional and physical level. Exposure to traumatic experiences can result in difficulties forming healthy relationships, poor emotional regulation, low self-esteem, and issues with attention and focus (Curriculum Review, 2017). In young people, the biological response to traumatic events can have adverse effects on long term health. In response to stress, the body releases cortisol (the stress hormone), which induces a state of “constant survival mode.” When this response is triggered over and over again, it placed undue burden on all bodily systems, and can cause immune and digestive health to deteriorate (Nealy-Oparah and Scruggs-Hussein, 2016, p. 13). In a young body, this sustained stress response can prevent healthy physical development, in addition to prohibiting normal emotional growth.

Trauma’s Presence in Schools

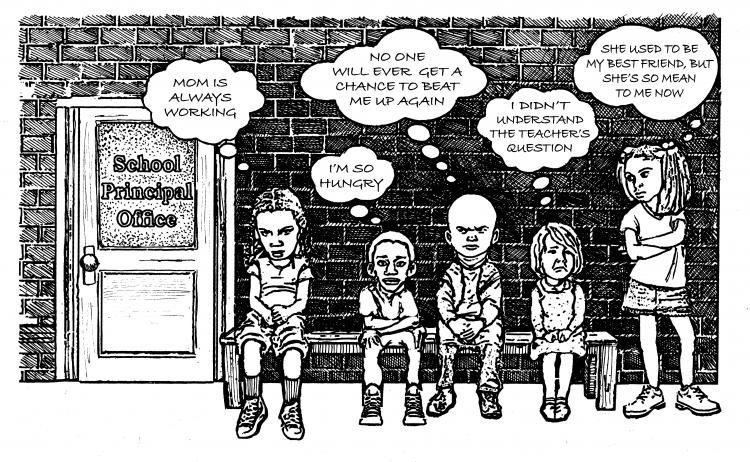

Experienced trauma does not require large-scale events such as natural disasters and school shootings. Neglect, abuse, homelessness, and even divorce can illicit trauma responses in students. Thus, about half of all students come to school having experienced some type of trauma in their lives (Curriculum Review, 2017). School can be an intense environment, and learning asks a lot of children, both intellectually and emotionally. Hence, school can be an environment full of triggers for students who have experienced profound emotional trauma, from the presence of authority figures, to social dynamics (Nealy-Oparah and Scruggs-Hussein, 2016). Every student working through experienced trauma had different triggers and different responses to their triggers.

How Should We Respond?

Consideration of the trauma students and their families have been through in school community building is referred to as trauma-informed schooling. Nealy-Oparah and Scruggs-Hussein propose that there are six key elements in building a trauma-informed school protocol: the first five of which have been previously researched and include

- high quality instruction

- heightened professional development

- creating a safe and reflective space

- flexibility among staff

- engaging with student bodies in healthy and positive ways

The sixth is a call for school staff to focus on building students’ social-emotional intelligence by fully participating in trauma-informed practices (Nealy-Oparah and Scruggs-Hussein, 2016). All adults in a school should be involved in treating trauma. Administrators have the power to organize staff training and encourage direct intervention by faculty (Curriculum Review, 2017). Recognizing responses to trauma and responding appropriately to associated behaviors is extremely important in effective treatment.