This project, and for that matter, this course as a whole, has really changed my perception of public education in this country and its relationship with the American citizenry. There are many ways in which my views have been shaped, however, I can condense what I’ve learned down to two ideas:

- The disconnect between what a community needs and what is offered to them through traditional public services

- The benefits community-based organizing can have for combatting institutionalized inequities.

Disconnect

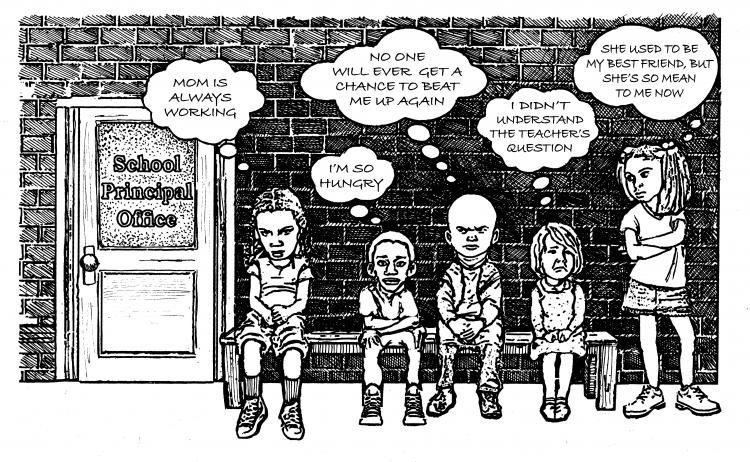

Through researching community organizing around trauma-conscious school discipline, it is clear to me that existing discipline policies were designed without real consideration of the populations they would be affecting. Especially in urban areas, zero-tolerance and no-excuses are common phrases used to describe discipline policies. These policies were born out of attempts to legitimize the education offered in cities, at a time when private and suburban schools were and continue to be held in much higher esteem than their inner-city counterparts. The students in these urban schools are judged to be badly behaved, undisciplined, and even “uncivilized”. Thus, the rhetoric that followed espouses that before the academics can improve, the behavior of the students must improve.

This narrative of how urban schools adopted zero-tolerance discipline practices stresses just how important community action is in these situations. Here, city, state, and federal legislators are crafting policy that directly affects the lives of millions of children in the absence of any real sense of their needs and challenges. Had the voices of urban communities been heard through the layers of historical marginalization, it would be harder to ignore the fact that these students are fighting against hundreds of years of economic and social barriers, and they have often experienced more trauma in their young lives than many more privileged adults will ever experience. Community organizing has the potential to help us bridge this gap between government and citizens, and stop the momentum of long-standing ideas about marginalized populations which often have roots in America’s racist and classist past. The voices of underprivileged communities must be heard, for the sake of the decriminalization of urban youth, and so many more societal issues.

https://www.afsc.org/office/new-orleans-la

Importance of Community Organizing

A community is not limited to the people inside a geographic area anymore; the presence of the internet allows anyone who has connected experiences or identities can form a community. However, only those living and working inside a community can fully understand what that community needs. Often, the communities represented in American governance have needs that current legislation supports and addresses readily. It is the needs of those underrepresented in American governance that need advocating for, which is where community organizing becomes incredibly helpful.

Due to the way American cities were built, poor residents are often sectioned off into dismal, dilapidated parts of the city, what some would refer to as “ghettos”. These areas of concentrated poverty, usually in relatively close proximity to the glittery economic centers of the cities they share, breed deep resentment and distrust of not only the government, but also of their very own community. This urban structure minimizes the collective power that these marginalized communities have, thus dissolving any chance they have of exerting influence over how institutions treat them and their homes. This connects us back to how zero-tolerance discipline policies were originally adopted: without any investigation into the needs of the people affected. In the current state of the U.S. government, community organizations are the best equipped to respond to injustices forced upon them.

Hope

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/mbas-across-america/team-harvard-bringing-nei_b_5621175.html

It is easy to become jaded about the future of urban schools, and by extension, urban communities, but it is the existing community organizations I have come across in my research that give me hope that there is change on the horizon. In New Orleans students are rebuilding their city after the devastation caused by hurricane Katrina, and local chefs and restauranteurs are using New Orleans’s culture of great food to help young people move past criminalization and offer more to their community. In Chicago and Ohio, students are coming together to challenge realities they face every day: zero-tolerance discipline and the school-to-prison pipeline. They are receiving support from their teachers, and, in some instances, even their school administrators. There is tremendous power in communities coming together to fix a communal problem, and I personally hope that this momentum builds until real change can happen on the local level for these communities.

Going forward, I know that the ways in which I have been challenged to think in this class will greatly benefit me. Although I do not have a clear idea of what I will be doing in the future, I know that I want to stay involved with urban communities in whatever capacity I can. The learning I have done in this class will help me be purposeful and conscientious in my participation in urban communities.