Overview

There exist a plethora of strategies teachers and administrators can employ to support ELLs. “Teacher leadership to support English language learners” by Felice Atesoglu Russell and Kerry Soo Von Esch shows how teachers and administrators can advocate for and help implement improved classroom support and instruction for ELLs. “Home-School Connections Help ELLs and Their Parents” by Corey Mitchell focuses specifically on strategies for engaging parents in their children’s education. While these articles demonstrate different ways of supporting ELLs, they share commonalities and, together, provide a broad conception of ELL support.

Administrative Support

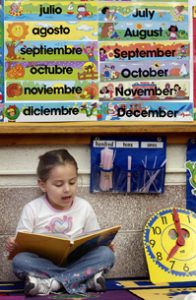

A student reads a book in Spanish in a bilingual classroom. Source: http://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre2009121100

Both articles’ recommendations require administrative support to execute. In one example Russell and Von Esch discuss, two teacher-advocates required principals who requested their services to develop an “ELL service plan,” which “forced principals to think more intentionally about how they could meet the needs of their English learners” (Russell and Von Esch, 54). This approach requires administrators to develop thoughtful support programs and holds them accountable for meeting the goals they set for English language support. Although in this strategy, teachers to guide principals in supporting ELLs, Mitchell shows how principals can also act unilaterally to provide ELL support.

Mitchell’s article highlights the work of Maria Arias Evans, a principal of an elementary school whose student body is composed of 80% ELLs. Arias Evans developed a program called Madre a Madre, where parents attend weekly meetings at the school in order to help foster a relationship between parents and the school. She also started an “open-door policy” in order to send the message to parents, “We expect you. We invite you” (Mitchell, 12). These kinds of programs came directly from the principal, rather than from teacher-advocates guiding principals to implement them. These two different frameworks show the importance of administrative involvement in ELL support regardless of whether the drivers of change are teachers or administrators.

Teacher Leadership

Russell and Von Esch’s and Mitchell’s articles both highlight work done by particular teachers in support of ELLs. Russell and Von Esch discuss three teachers who are providing ELL support in their schools. Robin and Beth were the teachers mentioned earlier who worked with principals on ELL service plans; they also developed relationships and shared knowledge with classroom teachers. Sarah provided modeling and coaching for teachers to help them gain ELL teaching skills, as well as served as an advisor to the principal on ELL issues. All three of these teachers worked both in classrooms with teachers and at the administrative level to help develop stronger ELL supports.

A teacher speaks at the front of a bilingual classroom. Source: https://www.languageconnections.com/blog/bilingual-education/

Mitchell highlights a teacher who went above and beyond in the development of home-school connections. Christian Rubalcalba “visit[s] the homes of all his students during the first moth of each school year” to strength then relationship between himself, students, and their families (Mitchell, 12). While Robin, Beth, and Sarah worked within the school, Rubalcalba works to incorporate home and family into the schooling process. Each of these extraordinary teachers modeled how teachers can be advocates for ELLs and ensure that these students receive a high-quality education.