Background

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) originates from tropical South- and Southeast Asia. The sugarcane plant produces sucrose and oxygen as a result of photosynthesis. Sucrose is extracted from the sugarcane then crushed and purified in mill factories to produce crystallized sugar. Sucrose can also be extracted from sugar beets. Refined sugar is further processed and is made up of a combination of cane and beet sugar. Molasses, a byproduct of the extraction and refining process of sugar, is often used for feed, food, alcoholic beverages and ethanol.[1] Sugarcane is a semi-perennial, deep-rooted crop belonging to the grass family that remains in the soil all year round and is harvested throughout the year. It can be harvested manually, using manpower and pre-harvest burning of straw to kill pests/snakes, or mechanically, using a combine on land that is a slope of less than 12 degrees. Sugarcane production cycles are usually 5-6 years long and then crop rotation occurs and the sugarcane is replanted.

Labor Exploitation

Sugar was an extremely important crop in colonization. Christopher Columbus first brought sugarcane to the Dominican Republic in the 15th century. Slavery was critical in sugar trade due to the extensive manpower required to plant, harvest, and process the crop. At first, indigenous people were enslaved, destroying indigenous populations and cultures, as well as European migrant laborers. Within a decade of Columbus’s voyages, large numbers of African slaves were brought across the Atlantic to the Caribbean. Over 300 years, more than 10 million Africans were forcibly brought to the Americas.[2] By the 18th century, people of European descent were significantly outnumbered by Africans. Today, exploitation of labor, including child labor, still exists in the sugar industry. Families of agricultural workers often depend on their children to take part in sugarcane planting, cultivation, harvesting, and processing because they need money, even though children earn extremely low wages. This exposes children to dangerous health conditions including insect or snake bites in the fields, injuries from machetes or machinery, long labor hours in strenuous conditions, and long-term health issues due to contact with pesticides or herbicides. In addition, sugarcane workers are prone to nutritional problem. Since many workers suck on cane to relieve hunger pains, this leads to long term malnutrition and dental decay. In order to remove children from hazardous work conditions requires “providing alternatives for families to earn sufficient income, better labour protection for adults, and greater educational opportunities for the children.”[3]

Production

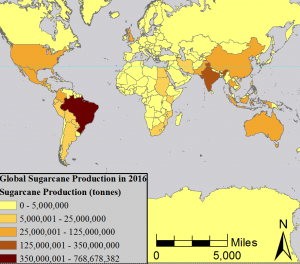

Although sugarcane is grown in over 100 countries, global sugarcane production is fairly concentrated in a few countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Global sugarcane production (in tonnes) in 2016. The top three sugarcane producers are Brazil (768,678,382 tonnes), India (348,448,000 tonnes), and China (122,663,940 tonnes) (FAOSTAT 2016).

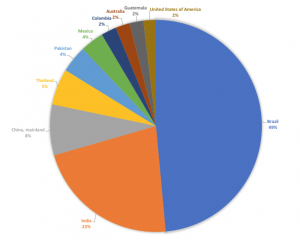

During the 20th century, India and Cuba were the two largest sugarcane producers in the world. Until 1991, Cuba played a large role in global sugar trade as a major supplier of sugar to the Former USSR.[4] During the past 30 years, Brazil has risen to the top of global producers, largely driven by domestic policies fostering bioethanol production. Brazil is the leading producer of sugarcane in the world. Brazil produces more than 768 million tonnes of sugarcane while India, the second largest producer in the world, only produces 348 million tonnes. China is the third largest sugarcane producer, producing 122,663,940 tonnes of sugarcane in 2016.[5] Out of the top ten sugarcane producers, Brazil accounts for nearly half (49%) of the sugarcane produced (Figure 2). Brazil’s sugarcane production is concentrated in the South-Central states, particularly in the state of São Paulo. São Paulo State is responsible for about 90% of Brazil’s total sugarcane production.[6]

Figure 2. This chart shows the top ten sugarcane producers in 2016 (FAOSTAT 2016).

Spotlight Issue: Sugarcane Expansion and Ethanol

Due to a rising demand for alternative fuels and flex fuel vehicles in the early 21st century as well as an increase in sugar prices in the international market, sugarcane cultivation expanded rapidly in São Paulo State, Brazil. Sugarcane areas increased over 4 million hectares in São Paulo State from 2005 to 2010.[7] Sugarcane expansion for ethanol production increased in 1975 when Brazil announced the National Alcohol Program, which blended around 20 percent ethanol with gasoline. After a decade of deregulation in the ethanol market from 1991 to 1999 and the inclusion of flex fuel vehicles in the Brazilian automobile industry in 2002, sugarcane production expanded.[8] In 2007, a “Green Ethanol” Protocol was established. This Protocol promotes sustainable sugarcane production practices in São Paulo State to improve air quality and “promote the improvement and conservation of native vegetation in São Paulo State.” It does this by aiming to end pre-harvest burnings, reducing the amount of water used in the industrial sugarcane crushing process, and recovering the riparian forests within sugarcane production regions.[9] São Paulo State, Brazil passed a law (number 11241) banning the pre-harvest burning practice that is required in traditional manual sugarcane harvesting by 2021. A 2011 study evaluated the effectiveness of the protocol and found that over the past five crop years, sugarcane harvesting expanded by 1.5 million ha, however there was no significant reduction in the amount of pre-harvest burned land over the same period. It predicts that the goal is likely to be achieved a few years later (2015-2016), which is still about five years before the 2021 goal in the State Law.[10]

Environmental Impacts

Sugarcane expansion has negative impacts on the environment. Sugarcane cultivation can cause soil erosion and degradation. Runoff of polluted effluent that is rich in organic matter can reduce oxygen levels in the water. Although most plantations are in areas previously used for animal crops, converting land into sugarcane production can contribute to biodiversity loss through destroying wetland habitat or habitat fragmentation. Also, pre-harvest burning practices contribute to air pollution by releasing carbon monoxide and ozone into the atmosphere (WWF 2005).

Future Implications

In order to minimize environmental degradation due to sugarcane cultivation, it is essential to monitor sugarcane expansion. There have been multiple sugarcane monitoring efforts in São Paulo State, Brazil using remote sensing techniques. Much of the sugarcane expansion in Brazil was driven by ethanol demands. With the inventions of many different types of alternative fuels and alternative energy, biofuels may become obsolete in the near future. Additionally, labor conditions must be improved in the sugarcane industry. In order to improve labor conditions and eliminate child slavery, poverty must be addressed by providing families with more options to earn enough income and educational opportunities for children. A potential strategy is to pay families money to keep children in school, help pay for groceries and necessities, and also send both girls and boys to school in order to combat gender divides. Although there are issues associated with corn, perhaps corn sugar is ethically better than cane sugar. Compared to sugarcane, there is arguably less exploitation of labor in corn production. This also raises the question of health and the necessity of sugar in our everyday lives.

Footnotes

[1] “Definition and Classification of Commodities: Sugar Crops and Sweeteners and Derived Products,” FAO, accessed May 5, 2018, http://www.fao.org/es/faodef/fdef03e.HTM.

[2] Heather Whipps, “How Sugar Changed the World,” June 2, 2008, https://www.livescience.com/4949-sugar-changed-world.html.

[3] Trebilcock, Anne, Sonja Zweegers, Jennifer de Boer, and Joel O. B. Marin, “Sugar Cane and Child Labour: Reality and Perspectives,” Ethical-Sugar, n.d., https://ethicalsugar.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/ethical-suagr-sugarcane-and-child-labour.pdf.

[4] Peter Zuurbier and Jos van de Vooren, eds., Sugarcane Ethanol (The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2008), 29-62.

[5] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2016, http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data.

[6] Adami, Marcos et al., “Remote Sensing Time Series to Evaluate Direct Land Use Change of Recent Expanded Sugarcane Crop in Brazil,” Sustainability 4, no. 4 (2012):574-585, doi: 10.3390/su4040574.

[7] Adami, Marcos et al., “Remote Sensing Time Series to Evaluate Direct Land Use Change of Recent Expanded Sugarcane Crop in Brazil,” 574-585.

[8] Bernardo F. T. Rudorff et al., “Studies on the Rapid Expansion of Sugarcane for Ethanol Production in São Paulo State (Brazil) Using Landsat Data,” Remote Sensing, 2 (2010):1066, doi:10.3390/rs2041057.

[9] Daniel A. Aguiar et al., “Remote Sensing Images in Support of Environmental Protocol: Monitoring the Sugarcane Harvest in São Paulo State, Brazil,” Remote Sensin,. 3, no. 12 (2011): 2683. doi:10.3390/rs3122682.

[10] Aguiar et al., “Remote Sensing Images in Support of Environmental Protocol: Monitoring the Sugarcane Harvest in São Paulo State, Brazil.”

References

Adami, Marcos, Bernardo F. T. Rudorff, Ramon M. Freitas, Daniel A. Aguiar, Luciana M.

Sugawara, and Marcio P. Mello. “Remote Sensing Time Series to Evaluate Direct Land Use Change of Recent Expanded Sugarcane Crop in Brazil.” Sustainability 4, no. 4 (2012):574-585. doi: 10.3390/su4040574.

Aguiar, Daniel A., Bernardo F. T. Rudorff, Wagner F. Silva, Marcos Adami, and Marcio P.

Mello. “Remote Sensing Images in Support of Environmental Protocol: Monitoring the Sugarcane Harvest in São Paulo State, Brazil.” Remote Sensing. 3, no. 12 (2011):2682-2703. doi:10.3390/rs3122682.

Fischer, Günther, Edmar Teixeira, Eva Tothne Hizsnyik and Harrij van Velthuizen. “Land use dynamics and sugarcane production.” In Sugarcane Ethanol, edited by Peter Zuurbier and Jos van de Vooren, 29-62, The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2008. https://www.wageningenacademic.com/doi/pdf/10.3920/978-90-8686-652-6#page=30.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2016. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data.

“Definition and Classification of Commodities: Sugar Crops and Sweeteners and Derived Products.” FAO. Accessed May 5, 2018. http://www.fao.org/es/faodef/fdef03e.HTM.

Rudorff, Bernardo F. T., Daniel A. Aguiar, Wagner F. Silva, Luciana M. Sugawara, Marcos

Adami, and Mauricio A. Moreira. “Studies on the Rapid Expansion of Sugarcane for Ethanol Production in São Paulo State (Brazil) Using Landsat Data.” Remote Sensing, 2 (2010):1057-1076. Doi:10.3390/rs2041057.

Whipps, Heather. “How Sugar Changed the World.” June 2, 2008. https://www.livescience.com/4949-sugar-changed-world.html.

Trebilcock, Anne, Sonja Zweegers, Jennifer de Boer, and Joel O. B. Marin. “Sugar Cane and Child Labour: Reality and Perspectives.” Ethical-Sugar. N.d. https://ethicalsugar.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/ethical-suagr-sugarcane-and-child-labour.pdf.