Although there were several instances of communal riots pre-dating the official announcement of the partition of the former British Indian Empire, the violence that erupted after August 15, 1947 was on an entirely different scale. The Punjab province, in particular, became a scene of incomparable carnage. G.D. Khosla described the riots as a “storm of lawlessness [that] attained a horror and destruction unequaled anywhere else.” The decision by lawmakers- far from the front-lines of civilian battle- to split the country along religious lines unleashed an episode of barbaric depravity likely unmatched in recent history. Partition would become the event against which all other acts of communal violence in South Asia- before and since- would be compared. And they have all remained in the bloody shadow of 1947.

Approximately one million people lost their lives during partition (some scholars estimate still more).

Aftermath of a Riot

An injured woman is carried by her male relations

Refugees recover from disease and starvation

Even amongst those who survived the butchery, hundreds of thousands were left with permanent injuries. Limbs were chopped off, bodies mutilated, and disease spread like wildfire in the unsanitary conditions of the fleeing hordes.

Accounts of the physical violence perpetuated between religious communities are both shocking and horrifying. Shane Ali is one victim and witness to this violence. His childhood village was attacked by a Muslim mob and, though he was physically spared, the scenes haunt his memory. As he talks about his harrowing experience, it is important to note not only the words he utters but the emotional aspects of his speech, from the moments of silence, to the trembling manner of his voice.

One of the defining acts of violence of Indian partition were the attacks upon trains carrying evacuees between the new India and Pakistan. Enclosed within small train compartments, or in large railway station crowds, masses were butchered within short periods of time in a brutal pattern of reprisals between communities. Such attacks came to be known as “trains of death.” Despite the prevalent (and, sadly, often truthful) rumors of trains arriving at their destination with only corpses, refugees flocked to the railway stations in a maddening scramble to escape to the country to which they suddenly “belonged.” A clip from Partition (2007) captures the atrocity of this kind of attack:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-vh2W4qEs4#t=22m35s&end=23m50s

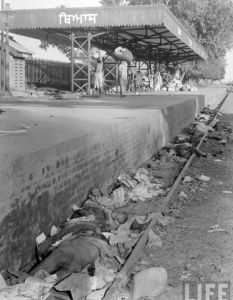

Corpses on the train tracks

It was not only trains en route that were attacked; members of both communities took advantage of the chaos to massacre the beggared crowds at train stations themselves.

An Improper Burial

Bodies were strewn on the train tracks to rot. Countless victims were never given proper burial due to the near complete suspension of law and order.

Mohammad Rafique Chaudhry traveled by train from India to Pakistan with his family. He witnessed a train massacre at Lahore station, a barbarous event that he “can never forget” as he had “never seen that many dead people.” Though the attack was on a train of Hindus and Sikhs (the very communities that were driving Chaudhry and his family out of India), Chaudhry recognizes the insensible brutality of this event and is horrified, even years later. His testimony is important not only as an account of a witness to this unparalleled violence, but as support to the argument that this kind of hatred was not necessarily a “natural” result of religious difference- there were (and are) those to whom this violence is inexplicable.

Dr. Hameeda Hossain, a Muslim woman, also witnessed Hindu refugees escaping Pakistan via train. Though she was a young teen at the time of Partition, Dr. Hossain remembers one incident in which she and her siblings and Muslim friends told a fleeing Hindu family to “go to [your] own country.” Such interactions between members of different communities were not uncommon at this time, as political rhetoric and ever-increasing violence drove religious groups apart. But although Dr. Hossain admits to participating in taunting the escaping Hindus, she also expresses her consternation at her actions. She does not remember why she chose to engage in such hateful speech, nor where she learned to do so; her family “never had this feeling” (implying that her family did not share the prevailing communal feeling). This incident begs the question: how deeply did communal hatred run? Though this question is not the focus of this study, it is an important one to keep in mind when studying this period. If the common people did not understand why they should hate the other community, was partition truly unavoidable? Were the one million deaths, one hundred thousands abductions, and fourteen and a half million refugees an inevitable result of Independence?