Do you eat fish at home or in restaurants?

Do you ever wonder why some fish are so much more expensive than others?

Or do you ever think, “how do fishermen and states track and manage so many fish as fisheries constantly change?”

Listen to the presentation below to get answers as you learn about the mackerel fishery in the North Atlantic Ocean – what is changing, why is it changing, and how is it impacting fishermen, state economics, and international cooperation?

[ensemblevideo version=”5.6.0″ content_type=”video” id=”31736b17-fb36-4010-9381-1746013a7bfb” width=”848″ height=”480″ displaytitle=”true” autoplay=”false” showcaptions=”false” hidecontrols=”true” displaysharing=”false” displaycaptionsearch=”true” displayattachments=”true” audiopreviewimage=”true” isaudio=”false” displaylinks=”true” displaymetadata=”false” displaydateproduced=”true” displayembedcode=”false” displaydownloadicon=”false” displayviewersreport=”false” embedasthumbnail=”false” displayaxdxs=”false” embedtype=”responsive” forceembedtype=”false” name=”International Management of the Atlantic Mackerel Fishery”]

Why is this case study important to the broader discussion of future fishery management ?

Under business-as-usual emission scenarios, fisheries situated in multiple EEZ’s (a.k.a. straddling fisheries) are predicted to increase by 35% by 2060 (Kelman 2020)

Background information on fisheries in Arctic geopolitics:

As ocean warming has notably accelerated over the past twenty years, fishery management in and around the Arctic circle has become more complex and contentious.

The varying symptoms of climate change in these marine environments, including surface water warming, ocean acidification, melting sea ice, changing nutrient upwelling patterns, and shifting currents, fishery populations, distributions, and migratory patterns are becoming less predictable.

In these regions, fisheries are managed in two ways: fish within 200 nautical miles of a state’s coastline are considered part of the state’s economic exclusive zone (EEZ) and are managed by the state while fish in international waters are generally managed by a regional fisheries management organization (RFMO). The driving challenge in this management scheme is comedically simple: fish don’t care about which EEZ or RFMO they are in or moving into. As climate change drives fisheries to visit new EEZs and RFMOs, systems of economic stability and international fishery management begin to fall apart.

What have we learned – themes and conclusions of this case study:

- Without a forum for discussion of contentious geopolitical issues or adequate representative of all stakeholders in the forum, it is harder to manage or solve problems – ignoring the issue (or excluding the stakeholders) does not prevent the issue from occurring but simply makes it harder to address.

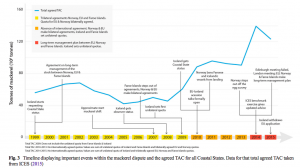

- In this case study, Iceland was initially denied a voice, and later denied legitimacy, on the forum for managing the mackerel fishery – this did not prevent Iceland from fishing mackerel but simply made it harder for the other mackerel-fishing states to sustainable manage the fishery or agree on annual total allowable catch (TAC) quotas.

- This overarching theme ties together the topic of international security and cooperation in the Arctic – the same challenge applies to demilitarization and security cooperation in the region.

- In the face of scientific uncertainty, states act with an emphasis on self-interest while sidelining international sustainable management efforts.

- Scientific uncertainty gave states the flexibility to create their own tracking systems, quotas, and management schemes, in order to match their “scientifically-measured fishing recommendations” with their economic interests (North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission 2017, 2018, 2019).

- The current legal frameworks for international fishery management and economic exclusivity do not have the built-in elasticity to flex or adapt to the ways in which climate change is impacting governance and cooperation in the Arctic (Spijkers, Boonstra 2017).

- Quota-setting organizations, such as the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), seem to be largely interesting in promoting international cooperation and the economic satisfaction of its member states as opposed to truly representing the ecological data and environmental warning signs (Poulson 2021).

“It’s miscommunicating how much we don’t know about this” -Dorothy Dankel 2021 (Poulson 2021).

What can be done – policy recommendations:

- There must be a more flexible, dynamic, non-binding management scheme – this must involve treaties, guidelines, and protocols for managing the fishery as it continues to change migratory routes.

- Within this scheme, zonal attachment (the principle that the number of fish by mass within a state’s EEZ equals their share of the fish in international waters) should be prioritized in this new scheme to account for the changing distribution of the fishery.

- There must also be incentive structures for multilateral sustainable management of the fishery – this would encourage a long-term extractive approach to fishery management.

- Policy makers, negotiators, and NEAFC organizers must invite representatives from relevant scientific institutions to participate in negotiations on Coastal State level and on NEAFC level – there, they can explain the uncertainty and buffer with which the TAC recommendations are made.

- Often, the challenge of scientific uncertainty destabilizing negotiations comes from the way in which uncertainty is communicated, not exclusively from the uncertainty itself.

- A precautionary management approach should be explored with the thought of considering a ban or steep reduction of mackerel fishing until a multilateral management agreement can be reached – this is based on the idea that resolving uncertainty thresholds, or at least understanding them, comes before exploitation.

- Precedent for this investigation is set in the Central Arctic Ocean and by the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC), where fishing in international waters has been paused due to inadequate ecological data.

- During the moratorium or reduction, fishermen could be given financial compensation for supporting or conduction research or could be encouraged, through subsidies, to explore regenerative aquaculture – seaweed, shellfish, and less tapped fisheries.

What else is there to wonder – ongoing challenges and questions:

- Will the mackerel fishery continue to move north, remain where it is now, or return to its previous migratory route (Spijkers, Boonstra 2017)?

- What exactly has caused the fishery to change?

- Changing surface water T, changing food distribution, changing population size (Jeffers 2010)?

- How much longer can the fishery be overexploited before it runs out?

- How will the fishing deal within Brexit affect the fishery and multilateral management?