“the Spirit of the Whale provides now, as it did [and] has throughout history, for our people, and lives within each of us”

Member of the Iñupiat at the Nalukataq festival

Overview

Similar to the other projects discussed in the traditional hunting group climate change is seriously impacting indigenous communities futures. Those impacts manifest in culture degradation as well as food security. My presentation gets at those same motifs through the case study of subsidence whaling in Alaskan communities. In this presentation, I will be particularly considering those communities in the Bering Strait, and Alaskan North Slope as well as northwestern Canadian communities that engage in whaling in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas. These communities are particularly interesting and useful to consider as they have engaged in subsistence whaling for thousands of years, since time immemorial but also because they are located in a region that is seeing the loss of sea ice and changing migration patterns of the bowhead whale the species which these communities rely on (Struzik, 2016). That makes this region a really useful case study in the intersection of food security, cultural integrity, and whaling.

Importance of Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling for Alaskan Communities

The importance is twofold, cultural and nutritional. Food insecurity is rampant among Alaska’s indigenous communities and that also has serious cultural implications and impacts on a sense of community.

Food Insecurity in these Alaskan Communities

Food insecurity disproportionately impacts these northern indigenous communities in both Canada and the United States. The Inuit Health Survey showed that adults living in Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR) experienced high prevalence of food insecurity 43.3%, compared to 9.2% for the Canadian national average (Rosol et al., 2011; Health Canada, 2007). Similarly, in Alaskan Native communities the burden of food insecurity was greater than the rest of the United states (Huntington et al., 2017). Given this great food insecurity and the benefits of nutrient-dense whale provides it is important to ensure these communities are not losing any more access to this important resource.

Cultural Importance of Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling

Cultural well-being and health in indigenous communities is closely tied to identity, positive family dynamics, social support, and spirituality (Egeland et al., 2009). All of these are offered by whaling (IWC, 2021). Being able to put this subsistence food on the table for your family is very important to members of the community’s mental health and identity. Being able to share your hunt with the community at Nalukataq, a celebration where the community comes together to feast after the bowhead harvest is also important to members identities (IWC, 2021).

Climate on the Ice and Whaling

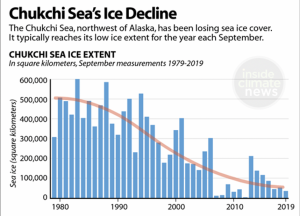

Global warming, similar to food insecurity, is disproportionately impacting northern latitudes when compared to the rest of the globe, as seen on this map where red indicates greater  warming (ACIA, 2005). This warming is not good for these communities. Warming makes the hunting and availability of the bowhead whale more difficult and dangerous. Nuiqsut residents recall their elders speaking about a time when warming and thus hardship would follow

warming (ACIA, 2005). This warming is not good for these communities. Warming makes the hunting and availability of the bowhead whale more difficult and dangerous. Nuiqsut residents recall their elders speaking about a time when warming and thus hardship would follow

(Struzik, 2016). In the 1980s indigenous communities mention sea ice 3-5 feet thick in March but now open water of very thin ice (Struzik, 2016).

Policy Initiatives

What policies or initiatives are being engaged with to ensure food security?

- Working towards ensuring food security, is the cooperation between SeaShare, a non-profit organization that facilitates donations of seafood to feed the hungry, and Alaskan seafood

and freight companies as well as the U.S. Coast Guard (Hill, 2015). In 2015, these groups coordinated a donation of 21,000 pounds of halibut to villages in western Alaska. This was able to get food to communities during a time that hunting is become more and more dangerous and unreliable. This, however, is not a good solution but certainly a valuable system to have in place. The bringing of food up to these communities is only a bandaide (Hill, 2015).

and freight companies as well as the U.S. Coast Guard (Hill, 2015). In 2015, these groups coordinated a donation of 21,000 pounds of halibut to villages in western Alaska. This was able to get food to communities during a time that hunting is become more and more dangerous and unreliable. This, however, is not a good solution but certainly a valuable system to have in place. The bringing of food up to these communities is only a bandaide (Hill, 2015). - The next policy is also to the end of food security and begins to get at the wound rather than just cover it like SeaShare. That is, that as of 2018 the initiative states, “status quo catch

limits would be renewed automatically” (IWC, 2018). This means that these aboriginal subsistence whalers no longer need to wait and hope that the IWC approves their whaling quotas, fearing if they will face harsher food insecurity and cultural degradation. However, due to challenges with quotas in the IWC as well as fears of politicization of the IWC the Alaskan Congressional Delegation brought forth the “Whaling Convention Amendments Act of 2018.” This amendment ensures and protect the rights of Alaskan aboriginal subsistence whalers. This ensures that Alaskan Native communities which rely on whales for food security and cultural richness are safeguarded in case of a shift in the IWC’s bowhead whale quota system, thus ensuring food security and their way of life (Alaskan Congressional Delegation, 2018).

limits would be renewed automatically” (IWC, 2018). This means that these aboriginal subsistence whalers no longer need to wait and hope that the IWC approves their whaling quotas, fearing if they will face harsher food insecurity and cultural degradation. However, due to challenges with quotas in the IWC as well as fears of politicization of the IWC the Alaskan Congressional Delegation brought forth the “Whaling Convention Amendments Act of 2018.” This amendment ensures and protect the rights of Alaskan aboriginal subsistence whalers. This ensures that Alaskan Native communities which rely on whales for food security and cultural richness are safeguarded in case of a shift in the IWC’s bowhead whale quota system, thus ensuring food security and their way of life (Alaskan Congressional Delegation, 2018). - This initiative really begins to address food security more directly. This is an initiative with Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission and the Weapons Improvement Plan (IWC, 2021; AEWC, 2021.).

This initiative aims to improve the harvest efficiency, this is a rate for the number of whales attempted vs the number actually caught. Improving the rate of successful hunts is vital as sightings of whales become more scarce. This initiative aims to do this by providing these hunters with penthrite a more power explosive than the black powder previously used (IWC, 2021; AEWC, 2021). This would reduce the number of whales that are struck and lost, kill the whales faster reducing their suffering, and increase the safety of hunters as the whale dies more quickly meaning they are in less danger from the thrashing dying whale in their skin-covered umiaqs or aluminum boats (IWC, 2021).

This initiative aims to improve the harvest efficiency, this is a rate for the number of whales attempted vs the number actually caught. Improving the rate of successful hunts is vital as sightings of whales become more scarce. This initiative aims to do this by providing these hunters with penthrite a more power explosive than the black powder previously used (IWC, 2021; AEWC, 2021). This would reduce the number of whales that are struck and lost, kill the whales faster reducing their suffering, and increase the safety of hunters as the whale dies more quickly meaning they are in less danger from the thrashing dying whale in their skin-covered umiaqs or aluminum boats (IWC, 2021).

Recommendations

I offer two policy recommendations that aim to aid indigenous hunters ability to catch the food themselves despite changing conditions. Based on my research I believe the following may be helpful:

- Further investment in this AEWC and Weapons Improvement Plan is vital.

Harvest efficiency rates will become more and more important to providing nutritionally and culturally to

Harvest efficiency rates will become more and more important to providing nutritionally and culturally to

these communities as whaling becomes more difficult. Therefore, I suggest bolstering this program. Increased funding, providing more communities with more access to these penthrite explosives, as well as educating these communities on their use and benefits to hunter’s safety and efficiency rates in catches. (IWC, 2021; AEWC, 2021) - Further, I recommend that funds be allocated from the state or federal government for larger and more sturdy boats to be made available to these communities. I stress made

available not forced upon them. Communities still used traditional skin-covered umiaqs and that is their right. However, I believe that offering larger boats to these communities will allow hunters to follow the whales further offshore despite less sea ice. Hopefully, allowing the continued reliance of whale for nutritional value and cultural cohesion (IWC, 2021; IWC, 2018; Struzik, 2016).

available not forced upon them. Communities still used traditional skin-covered umiaqs and that is their right. However, I believe that offering larger boats to these communities will allow hunters to follow the whales further offshore despite less sea ice. Hopefully, allowing the continued reliance of whale for nutritional value and cultural cohesion (IWC, 2021; IWC, 2018; Struzik, 2016).

[ensemblevideo version=”5.6.0″ content_type=”video” id=”015fe9da-39c7-4f30-aeb7-e566216b29df” width=”848″ height=”480″ displaytitle=”true” autoplay=”false” showcaptions=”false” hidecontrols=”true” displaysharing=”false” displaycaptionsearch=”true” displayattachments=”true” audiopreviewimage=”true” isaudio=”false” displaylinks=”true” displaymetadata=”false” displaydateproduced=”true” displayembedcode=”false” displaydownloadicon=”false” displayviewersreport=”false” embedasthumbnail=”false” displayaxdxs=”false” embedtype=”responsive” forceembedtype=”false” name=”Climate Change on Aboriginal Whaling” description=”Max Muradian”]