“We walk the shores, woods, wetlands, caves, mountains where we can see or hear fowl, animal, or fish life, with insects and plant life and thus begin our talks and stories with those around us to pass on our language, knowledge and world view as an eco-centric people”

Katherine Sorbey – Mi’Kmaq, Canada

“We need perspectives from multiple scientific disciplines, but we need perspectives from Indigenous elders and the knowledge that they’ve acquired. I think if we don’t do that, we are doing a disservice to the science and understanding the changes in the Arctic.”

NSF Arctic science program director Colleen Strawhacker

Our world is turning to the North more than ever for answers, information, and solutions to climate change. Arctic imagery is becoming synonymous with the fight for environmental protection and climate action. People feel an emotional attachment to the arctic’s wild landscape and a desperation to save it. But when the NGOs and scientific institutions suddenly decide they must now know all things “Arctic”, they often forget there is already an established database of ecological knowledge within Indigenous culture.

Traditional ecological knowledge is not understood well in mainstream Western society; the most common stereotype is the belief that this knowledge system is outdated, inaccurate, inflexible, and not useful on a global scale. This could not be farther from the truth. In actuality, Indigenous culture holds some the most reliable ecological knowledge on the planet. Their methodology for examining their physical surroundings has truly been “peer reviewed” over generations and generations. But as we have seen in the case studies of whaling and sealing, these misconceptions have had disastrous effects on indigenous economies, livelihoods, and physical and emotional health. Thankfully, the path towards inter-knowledge understanding and collaborative research is beginning. There are new research models that spur community involvement and indigenous leadership. But in the Arctic, any decision to collaborate with indigenous peoples is generally at the discretion of the scientist or participating institution. We need policies within the international community to foster this type of collaborative research and respect of indigenous knowledge sources.

If you have not done so yet, please check out the case study pages for more specific information relating these traditional hunting communities!

Current Collaboration Efforts

One of the most successful collaboration models between indigenous peoples and western science is facilitating community-based monitoring research projects. Traditional hunters observe and monitor the ecology and climate around them everyday. Their access and understanding of the region is unparalleled. Although there is little policy demanding Indigenous collaboration in Arctic science, many researchers and community members are already expanding models of collaboration. The image below depicts a project at the Nunavik Research Center in Quebec, Canada.

Nunavik Indigenous elder maps Arctic char populations

This Indigenous led research center has a traditional ecological knowledge database that stretches back to the 20th century. Detailed interviews with hunters who travel through the region on ice have created more than 86,000 geographically-referenced data entries on plant and animal species, travel routes, ecology, and ice information. Community based monitory is not just small scale science. Adam Lewis, the engineer behind the center’s remote satellite monitoring describes the successful structure of the Arctic Char monitoring program:

“This project is quite unique in that we will use the traditional ecological knowledge to cross-check our scientific observations and measurements. The project is distinct in that usually when traditional ecological knowledge is used in conjunction with scientific data, the “science” forms the main basis of the observations, while TEK is used merely as an extra reference. In our project, however, we’re doing the reverse. “

In another example, the Smithsonian Arctic Studies center invites seal hunters to contribute to their documentation of sea ice knowledge. The Sea Ice Knowledge and Use project Nunavik Research Center records ice and ice use data from indigenous communities along the Bering Strait. Igor Krupnik, the curator of the Arctic Studies center describes on facet of indigenous culture preservation in the project:

“You could say that we are documenting “endangered knowledge about shrinking ice.” In some places we do not know which is going to last longer: the sea ice in its present condition or the knowledge about the sea ice that in many places is becoming endangered because of the economic changes or language transition”

Meanwhile in Finland, the Skolt Sami people of Finland collaborated in a federal study on the declining population of Atlantic salmon. The study is part of an ongoing project between the Sami people and Finish government called the Snowchange Cooperative. The study’s focus on salmon populations as an indicator of environmental change created an enormously successful publication in Science the following year.

From the project the Sami people are adapting fishing techniques and targeted species to help steward a stronger population of young salmon. It is clear from these collaborations that the benefits from knowledge sharing are bilateral and strong. To explore these phenomenal collaborations, and even more please check out the How to Get Involved in Arctic Policy Page!

Utilizing Institutions to Promote Collaboration: A Need for Policies of Inclusion

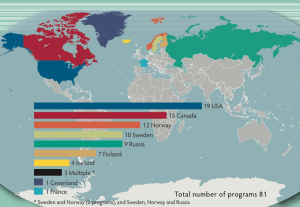

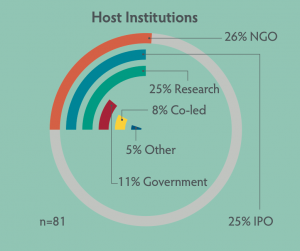

There are certainly beautiful and robust examples of collaborative knowledge production between Western scientists and Indigenous peoples. But are these examples indicative of a large regional shift towards indigenous inclusion? A review of programs incorporating community based monitoring systems in the Arctic generated the following data:

A clear pattern emerges: community based monitoring is centralized in North America and in projects led by non-governmental organizations and international policy organizations.

The International Arctic Science Committee is a non-governmental organization that facilitates and oversees collaborative international research efforts in the region. The institution consists of working groups that monitor the Arctic’s cryosphere (ice), atmosphere, marine environment, terrestrial environment and social research. Their office has issued a commitment to the preservation and inclusion of traditional ecological knowledge, but not one of the scientist representatives to each working group claims works with indigenous knowledge in the scientific realm this is a far cry from their office’s declaration on knowledge co production.

Our policy recommendation for the IASC is to create a permanent working group on the intersection of institutional science and traditional ecological knowledge. Additionally, their role as a facilitator of all international research projects can positively impact hundreds of projects. The creation of trainings and standards for indigenous collaboration, as well as community based monitoring, would empower many developing scientists to explore community based monitoring in their own research.

The Arctic Council‘s role in ecological research through the Assessment and Monitoring Program is another critical access point to the international environmental arena that can be used to raise indigenous voices. My policy recommendation to the Arctic Council is to use this program’s existing structure to monitor the inclusion of indigenous voices in Arctic research. The council should begin by creating a community based monitoring projects with the research institutions involved in the assessment program.

[ensemblevideo version=”5.6.0″ content_type=”video” id=”5c7f18a0-c134-4060-89b9-829b1499175c” width=”640″ height=”360″ displaytitle=”true” autoplay=”false” showcaptions=”false” hidecontrols=”true” displaysharing=”false” displaycaptionsearch=”true” displayattachments=”true” audiopreviewimage=”true” isaudio=”false” displaylinks=”true” displaymetadata=”false” displaydateproduced=”true” displayembedcode=”false” displaydownloadicon=”false” displayviewersreport=”false” embedasthumbnail=”false” displayaxdxs=”false” embedtype=”responsive” forceembedtype=”false” name=”Ind. Knowledge Video for Website”]