The Arctic is home to over 40 different Indigenous groups, each with its own culture and traditions. In the remote regions of the Arctic, hunting is not only a tradition but a necessity. Arctic animals provide essential food and crafting materials in a region where food is scarce and expensive to transport.

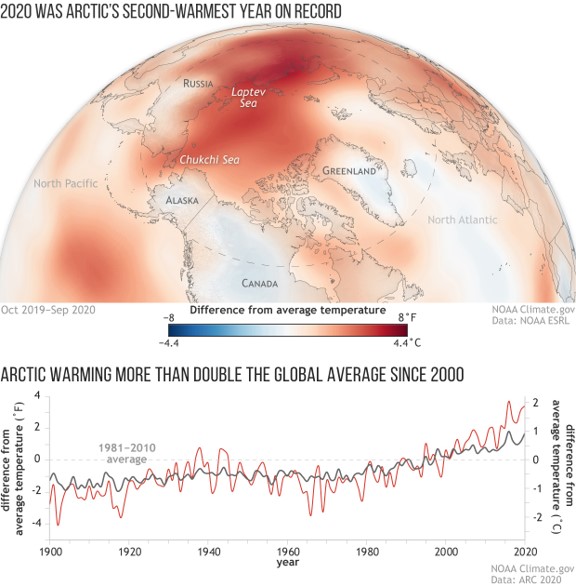

The Arctic is both the fastest warming region in the world and one of the regions with the most food insecurity. These two challenges have made hunting complicated, yet essential. Indigenous groups have had to adapt to environmental, cultural, and technological changes to their traditional hunting practices.

Traditional hunting has undergone many changes in the last century alone, as Indigenous hunters have incorporated new technology and methods into their hunts. Melting ice and warming seas threaten important animal populations and force migrations away from Indigenous communities. This website seeks to illuminate the underlying connections between seemingly unrelated challenges Indigenous groups are facing regarding the complex dynamic between hunting and climate change. Understanding these complex issues allows for a more robust dialogue around the most important reactive measures and policy initiatives to maintain what is left of the Arctic and support the most vulnerable indigenous groups and their traditional cultures.

Current Challenges: Four Case Studies

We studied three examples of traditional hunting practices, identifying the challenges and adaptations Indigenous communities are facing. We also explored how Indigenous knowledge can be incorporated into Arctic ecology. Our research revealed four case studies of how Indigenous communities are adapting to a variety of global changes and what we can do to help them.

Sealing

Inuit communities in Canada have hunted seals for centuries. Yet international condemnation of what is seen by outsiders as a “barbaric” practice has seriously damaged Indigenous economies and communities. The case of sealing in Canada raises a number of important questions: How does international policy affect Indigenous communities? How are Indigenous peoples maintaining their culture despite backlash to some of their practices? How do we strengthen Indigenous economies threatened by the collapse of the seal trade?

Caribou Hunting

Caribou populations in the Arctic are facing some of the challenges climate change has brought to the region. The warming climate has increased mosquito populations, which can seriously harm and harass caribou. Climate change has also led to trophic mismatch for caribou, meaning their food sources are emerging earlier in the season, becoming inaccessible to migrating caribou and their young. Because of these challenges, caribou populations in the Arctic are decreasing. Indigenous peoples rely on caribou as a source of food and materials, and their disappearance would be devastating for the Indigenous cultures in which they hold traditional significance. How can we save caribou populations in the face of a warming climate? How can we include Indigenous knowledge in further research?

Whaling

Whales are another important aspect of cultural heritage and a resource for Indigenous food security in the Arctic. Unfortunately, whale populations are also facing the consequences of climate change, as their populations have decreased and their migration patterns have changed. These changes pose a number of questions: How can Indigenous whaling remain sustainable and efficient while still addressing the food insecurity in Indigenous communities? How can national and international legislation protect vulnerable animal populations? How can technology increase the efficiency of Indigenous whaling?

Using Indigenous Knowledge in Arctic Ecology

Indigenous knowledge is often dismissed as outdated or unscientific, but that could not be further from the truth. Indigenous communities have observed and engaged with their surrounding environments for hundreds of years, passing knowledge and history down from generation to generation. International institutions like the Arctic Council have begun to acknowledge the value of Indigenous knowledge, encouraging collaboration between scientists and Indigenous peoples. However, there is plenty of progress to be made in fully incorporating and working with Indigenous people in research on Arctic ecosystems. Our case study explores the following questions: What does collaboration with Indigenous peoples look like in the research field? How can international institutions encourage the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in international research? How can the general public engage in and learn about Indigenous knowledge?

- Cross-Case Study Analysis:

- These four views of challenges in Indigenous communities all have several common threads: climate change and the lack of indigenous representation and knowledge including in decision making processes. Climate change has affected the caribou population and the safety of whale hunting, requiring decisions to be made on the international level about how to best address the problems. Indigenous groups span country borders, requiring a broad conversation that includes many international actors and can easily overshadow th

A Canadian Inuit community poses wearing seal products.

e voices of the indigenous groups in the center of the issues. This begs for more direct indigenous representation and a stronger connection between traditional knowledge and western science. Additionally, as new technologies enter the Arctic, discussions about modernization and the best ways to integrate indigenous cultures and modern technology regarding climate change adaption or life more generally are crucial. The Arctic is modernizing and indigenous voices are necessary to make sure the changes do not compromise cultural practices or heritage. These are complex issues, asking questions such as: how do we best integrate modern technology into whaling practices to reduce the new dangers presented by climate change while increasing the effectiveness of current practices? Or how do we support caribou populations in the face of trophic mismatch? Or will the seal industry rebound after the sealing bans, and how do we support communities detrimentally affected by the collapse of the industry? These require us as citizens to think about who makes the policies impacting Arctic communities, and how our politicians impact the international discussions. They require us to incorporate traditional knowledge into decision making practices and give platforms to the marginalized voices. While these case studies are complex and unique, together they help frame the necessary discussions relating indigenous communities and climate change in the wake of the world’s current climate crisis.

Climate Change as a Threat:

Unfortunately, negative changes as a result of the warming temperatures are apparent in indigenous hunting practices. The warming Arctic continues to melt permafrost and sea ice, forcing indigenous communities to abandon their traditional hunting practices, face increased danger, or lose relationships with species integral to their economies or survival such as seals or caribou. Unfortunately, as dialogues around ways to adapt to climate change continue to increase through organizations such as the Arctic Council, indigenous voices are continually underrepresented. Traditional knowledge is seen as outdated, especially when climate change discussions are dominated by research conducted through western science. Organizations continue to discuss the fast-paced changes related to climate change without strong indigenous inclusion, despite the fact that the indigenous communities are on the frontlines of the negative impacts, especially relating to their hunting and economic activities through practices such as sealing. Climate change not only poses a physical threat to the safety and livelihoods of indigenous communities and their relationships to the flora and fauna of the region, but also the inclusion of indigenous voices. New climate research is dominated by data acquired by western scientists, adding additional emphasis on the marginalization of traditional knowledge. How can indigenous issues be resolved with inclusion of the indigenous voices themselves? How can we work together to incorporate indigenous knowledge and experiences into international discussions, to better strengthen our responses to warming temperatures?

What can we do?

Learn more about policies in action on our policy specific page, but know that these challenges are resolvable with persistent, inclusive dialogues. The Arctic Council currently includes indigenous groups as “Permanent Participants,” however this role is limited and does not give these groups the ability to vote on important decisions. Additionally, there are many small projects working to increase indigenous representation and understand the impacts of climate change on hunting, whaling, and sealing. Check out our other resource pages for specific ways to get involved, websites to go to for more information, and more details on our policy recommendation and current Arctic efforts!

Glossary/Important Terms:

The Arctic: The region typically defined by the area north of the 66 degree latitude line. Scholars also use treeline to help identify what constitutes the Arctic region. States with Arctic territory are the United States, Canada, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Russia, and Sweden.

Traditional Knowledge: Traditional knowledge is knowledge gained through lived experiences and passed down from generation to generation. In the Arctic, traditional knowledge is connected to the indigenous groups who have lived in the region for many years.

Western Science: The knowledge system based around the scientific method and hypotheses/data collection. In contrast to traditional knowledge, this knowledge is acquired through testing, analysis, and reasoning rather than lived experiences. In the Arctic there is many times a conflict or disconnect between the traditional knowledge and western science when making decisions.

Inuit: An indigenous group in the Arctic residing mostly in northern Canada and Greenland.

Indigenous: The native peoples to a specific place or region. Examples of indigenous groups in the Arctic are the Saami, Inuit, and Yupik, among many others.

Permanent Participant: The status given to indigenous peoples’ organizations in the Arctic Council. They have the ability to weigh in and influence decision making but cannot vote in the voting process.

Arctic Council: Founded by the Ottawa Declaration in 1996, the Arctic Council is a peaceful, international organization led by the A8, or 8 Arctic States, that oversees Arctic affairs and cooperation in the region. Including the A8, Permanent Participants, working groups, and observers, the council conducts research, hosts discussions, writes policy, and votes on important issues relating to the Arctic and indigenous groups who live there.