While we can learn important lessons regarding nuclear proliferation, it is often difficult to make broader parallels to non-state actors due to the changing structure of war and international security. History often provides a good set of guidelines through which we can conduct policy regarding nuclear technology due to past experiences like the Cold War, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Damascus Incident. Governments and groups like the U.N. and NATO can learn a great deal from past experiences as long as they are able to relate these events to modern-day social and diplomatic contexts.

However, difficulty arises when comparing modern-day issues such as those involving non-state actors to historic contexts where these problems were not as prevalent. Evolving military tactics and substantial technological growth have resulted in four clearly-defined generations of warfare. The newest generation of warfare, or 4G warfare, consists of non-state actors utilizing guerilla tactics. These actors operate differently from conventional government structures, and in ways previously unseen in historical examples. While lessons learned throughout history might not clearly relate to new terrorist or insurgent groups, one can still examine broader structures like coercion and just war theory to better understand non-state actors.

While nuclear warfare is still a fairly new issue in international security, it relies on critical assumptions about how the discourse surrounding the subject is conducted, and how those involved are expected to act. This is because although generations of warfare have changed drastically, the first three still revolved around state actors with well-established militaries and clearly-defined procedures. This new, fourth-generation warfare, defies previous norms as it “uses all available networks… to convince the enemy’s political decision-makers that their strategic goals are either unachievable or too costly for the perceived benefit” (Hammes). Instead of state actors battling other state actors, non-state actors like insurgent or terrorist groups operate in large, complex networks to achieve their individual goals. Because it defies all previous notions of global conflict, it is often extremely difficult to connect past lessons to current struggles.

Non-state actors place increased importance on denying information about themselves to their opponent, which further disadvantages governments who seek to identify chains of command and members of these groups (Griffith). Parallels drawn between historical issues and modern-day nuclear proliferation are reliant on access to information. The deliberate restriction of information by non-state actors and the lack of previous knowledge surrounding these groups hinder most ties between previous generations of war and challenges of the 21st century (Hoffman).

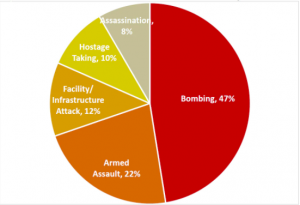

The use of force by non-state actors challenges historic combat strategy and further restricts parallels from being drawn between the past and present. While state actors utilize large military budgets for weapons, surveillance, and soldiers, terrorist and insurgent groups are limited in their resources. As a result, we see the indirect use of force and strategic use of violence in order to send a message and achieve their goals.

Some scholars believe that past nuclear strategy is not applicable to modern nuclear proliferation, mainly in North Korea and Iran. They argue that these states are unpredictable, and therefore would not follow the same logic as past nuclear states. In the case of North Korea, the racial theory of threat perception may help rationalize the security implications of racial prejudices. In international politics, “unit similarity decreases threat perception and facilitates discord” (Búzás, 576). Conversely, when identities are seen as divisive, cooperation can become undermined and the perception of threat is amplified.

In the case of Iran, Lewis claims that the concept of mutually assured destruction (MAD) would not apply to Iran because of what he describes as an “apocalyptic worldview of Iran’s present ruler” (Lewis). However, the historical record illustrates that this claim has little to no legitimacy (Waltz). Additionally, Kroening argues that a nuclear-armed Iran would be emboldened to “close the Strait of Hormuz, conduct massive and sustained attacks on Gulf states and U.S. troops or ships, or launch terrorist attacks in the United States itself (Kroenig, 83). Also, there are growing concerns that due to Iran’s ties with various terrorist organizations, they may directly or indirectly provide nuclear arms to non-state actors.

There is no doubt that nuclear-armed terrorists would present a major security threat, however, we do not think this would be likely. First, Iran would logistically not be able to transfer nuclear arms to terrorists as “U.S. surveillance capabilities would pose a serious obstacle” and the U.S. would likely be able to quickly “identify the source of fissile material” (Waltz, 4). Moreover, no state would logically provide weapons as powerful as nuclear arms to a third party, as it would risk its own destruction. Graham explains, “it is incredibly unlikely that any state, regardless of its ideological inclinations, would knowingly allow nuclear weapons to fall into the hands of actors it did not directly control, simply out of fear that the weapons might then be used against it” (Graham, 59). Therefore, the argument that past scholarship on deterrence does not apply to Iran is unfounded.