In 1977 with the completion of the trans-Alaska pipeline and the Valdez tanker terminal, a new system of oil transportation that promised to quench America’s appetite for fossil fuels and mitigate its reliance on Middle Eastern resources had been established. During its initial 12 years, the system was a huge success as tankers safely transited the Prince William Sound more than 8,700 times and transported around 2 million barrels of oil from the Alaskan pipeline into the American markets every day. Yet, despite its successful track record, the Valdez transportation system was permeated by lax governmental oversight and corporate disregard for safety protocols.

March 24th, 1989: The Grounding of the Exxon Valdez

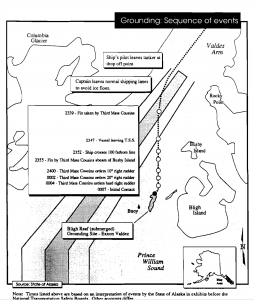

Around 9 pm on March 23rd, 1989, the Exxon Valdez, carrying over 53 million gallons of North Slope crude oil, left the Alyeska pipeline and began its journey towards Long Beach, California. As the boat had made its way through the Valdez Narrow at 11:30 pm, Captain Hazelwood, the person in command of the tanker, increased the speed of the boat and informed the Vessel Traffic Center that “we’ll probably divert from the TTS [traffic separation scheme] and end up in the inbound traffic lane.” As it was later learned, Hazelwood’s decision to deviate from the inbound navigation lane was done in order to avoid hitting small icebergs from the nearby glacier––icebergs which tankers can push through safely if they reduce their speed.

At midnight, the mate spotted waring lights from Blight Beef and attempted to re-steer the ship to avoid the shallows, but it was too late. Seven minutes later, at 00:07, the Exxon Valdez made contact with Blight Reef. Hazelwood, who at this point had been called back to the bridge, radioed the traffic center at Valdez: “We are fetched up, ah, hard aground…evidently leaking some oil.”

First-Response: The Clean-Up Fiasco

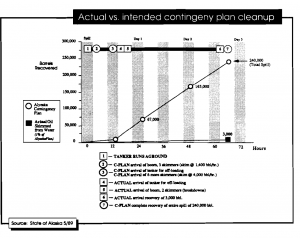

Within twenty minutes of Hazelwood’s communication, the Alyeska Piper Service Company––the corporation in charge of the initial clean-up response––was notified of the accident. Even though Alyeska’s contingency plan had estimated that it would take them around five hours to respond to an oil spill in the region, on the night of the disaster it took them over 14 hours. The delayed response time of the Alyeska was the result of a lack of preparation. Most of the Alyeska’s clean-up material was either missing or covered in several feet of snow, their 126-foot flat-deck trailer designed to move equipment during spill disasters was out of service and unloaded, and none of the employees working at the time were qualified to operate the forklifts required to move the equipment around. Alyeska’s clean-up response was a total failure.

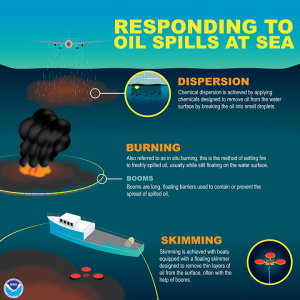

In an attempt to mitigate the impacts of the oil spill, Exxon quickly hired a private company to supply clean-up labor and material equipment. Despite their best efforts, Exxon was unable to collect the necessary oil containment equipment fast enough to stem the dispersion of the oil and engage in situ burning (see image). The initial attempt to contain the oil spill and prevent it from spreading across theGulf of Alaska had failed––the oil spill, which had spread thousands of miles, was now everywhere. Over the next couple of months, Exxon hired cleanup workers and local volunteers who skimmed oil from the water’s surface, washed oiled beaches with water hoses and cleaned animals trapped in oil. Yet, despite spending $2 billion on cleanup costs, Exxon’s efforts only removed around 3% of the total oil spilled and were deemed ineffective.

Aftermath: The Devastation of the Local Communities

In the aftermath of the disaster, the local communities of the Alaskan Gulf were devastated. As the oil spill spread and reached the shores, the land and waters by which these communities lived and relied on became toxic dumps. Furthermore, the influx of people that came to the area during the clean-up effort––reporters, out-of-state clean-up workers, and Exxon personnel––further exacerbated the hardship of the disaster. While the effects of the oil spill affected communities differently, Alaskans from all walks of life experienced economic loss, psychological trauma, and dislocation as result of the disaster.