The Great Chicago Fire of 1871

Origin

On the evening of October 8, 1871, a fire broke out on the O’Leary property on the southwest side of Chicago. There is a legend that a cow in the O’Leary’s barn kicked over a lantern, causing the fire that destroyed a good portion of downtown Chicago, however, the actual cause of the fire is still unknown and will likely remain that way.

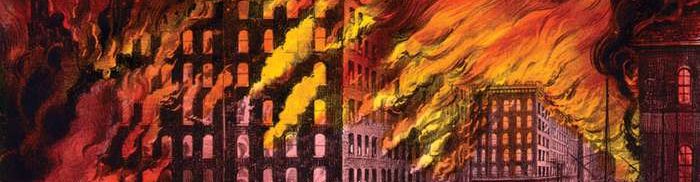

Prior to the commencement of the fire, Chicago had been experiencing a major drought, only receiving ¼ of the rain it usually does in the months of July through October. Additionally, the structures in the city were primarily wooden, from the buildings to the sidewalks, and essentially served as kindling for the fire. The dry environment combined with the strong winds in Chicago allowed for the fire to spread rapidly throughout the city, growing out of control as it destroyed building after building as it moved northeast toward the city center. The day prior to the Great Chicago Fire, there had been another major fire that left firefighting equipment damaged and firefighters exhausted, potentially slowing the response rate when the fire broke out the following day. The fire burned all throughout the night and the next day, finally coming to an end on the morning of October 10th with the assistance of rainfall and a section of unbuilt lots on the North Side of Chicago (Britannica 2020).

Destruction

Wooden structures in the city were simply kindling for the great fire as it spread rapidly throughout Chicago toward the city center & business district which was eventually left in ruins

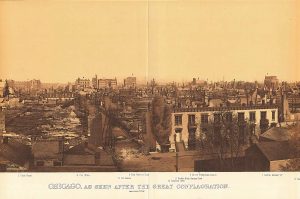

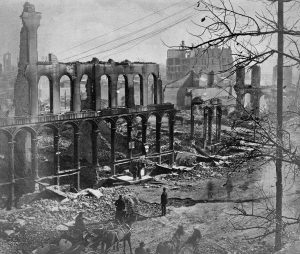

In the end, 17,000 structures had been destroyed, 300 people had died, and 100,000 people, one third of Chicago’s population at the time, had been left homeless. The result was utter chaos in the streets. An outbreak of looting and lawlessness led a group of elite business leaders in the city to persuade Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan and five companies of infantry to take control of law enforcement in the city, enacting a period of Martial Law on October 11th, the day after the fire had finally ceased. The troops attempted to restore foundations of social stability, patrolled Chicago’s central business district, and in their minds, the most important job of all, protecting wealthy neighborhoods and safeguarding valuable property. The city’s business elites felt a sense of responsibility to take control and adopt leadership roles in the aftermath of the fire as they believed the city’s politicians were far too “corrupt” and “incompetent” to restore stability in the city (Adler 1997, p. 254). However, this was a major point of contention among Chicagoans at the time due to the fact that many of the policies that the wealthy elites were implementing were not neutral and reflected only the particular visions and opinions of the wealthiest, upper-class Chicagoans. In the minds of the elite, these policies were fair, nonpartisan, and would benefit the general public, when in reality, they simply “safeguarded private property, celebrated self-reliance, and shored the city’s class structure” (Adler 1997, p. 253) in their elite crusade.

17,000 structures burned to the ground

Competing Visions of Civic Order

These competing visions of civic order were the root cause of a series of public-policy debates in the years following the Great Chicago Fire. This struggle and contention to reconstruct civic order in the aftermath provides a glimpse into the status of class relations at the time of the fire (Adler 1997, p. 257).