As outrage grew following the tragedy at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, the city struggled on where to place blame. While many simply saw the incident as accidental–a brutal, yet completely random, disaster–others blamed the oppressive Triangle factory owners, as well as the overall norm of worker suppression that was characteristic of sweatshops at the turn of the twentieth century. As the days passed and tensions only continued to grow, a criminal trial commenced. Analyzing the transcript of the trial of Max Blanck and Isaac Harris provides not only insight into who was to blame, or not to blame, but it also showcases many of the biases and misconceptions that were laid bare following the disaster at Triangle.

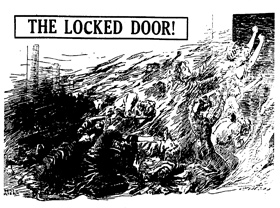

The New York City District Attorney filed seven counts of indictment about Harris and Blanck, one of which was the first degree manslaughter of Triangle worker, Margaret Schwartz. The thirteen week trial centered upon the locked Washington Street Door; according to prosecuting attorney Charles S. Bostwick, since the door was illegally locked during working hours, Harris and Blanck therefore caused the death of Schwartz during the fire.

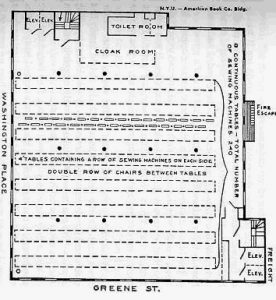

In his opening statement before a jury of twelve men, Bostwick carefully laid out the charges against Harris and Blanck. To begin, Bostwick thought it wise to “stop for a moment” and provide the jury with a sense of the floor plan (Transcript, 5). Bostwick claimed that, “beside the mere words ‘Green Street’ and ‘Washington Place,’” having some “definite and fixed notion as to the location” was necessary so “that we may understand each other” (Transcript, 5). Bostwick utilized the courtroom itself as visual aid, providing a holistic layout of the ninth floor of Triangle for the jury.

After grounding the jury within the physical space, Bostwick set the scene of the fire, specifically when the textile workers, including Margaret Schwartz, ran to the locked Washington Place Door: “it is for her death that these defendants are now on trial. Gentleman of the jury, that door was locked. Those who ran to that door cried out ‘That door is locked. My God, we are lost.’ They were lost. That locked door barred their escape” (Transcript, 10). Bostwick ended his opening statement laying out the legal precedent for the charges brought against Blanck and Harris: a locked door during factory hours was a misdemeanor, and if a death results from a misdemeanor it is deemed manslaughter. Despite the straightforward reasoning, Bostwick’s case fell completely on whether or not the Triangle Factory owners knew that the Washington Place Door was locked at the specific moment of the deadly fire. It is on this point that, despite over the one hundred witnesses and thirteen weeks of trial, the prosecution was unsuccessful. While the case of proving that the two defendants knew of a locked door at a specific was already a difficult case to prove, it was not made easier by the work of defense attorney, Max D. Steur–a Jewish immigrant and once garment sweatshop worker turned successful, cutthroat defense lawyer (Cornell University–ILR School).

Bias in the Trial

Throughout his often brutal cross-examinations, Steur undermined the words of the surviving Triangle workers, relying on all the biases that made this demographic vulnerable to the oppression of the Triangle sweatshop in the first place. Their age, gender, status as immigrants, and language abilities were all flaunted throughout the trial, as Steur effectively cast reasonable doubt upon the words of the young women in the eyes of the all-male jury.

Steur’s cross-examinations played on the bias of the stereotypical sweatshop worker at the turn of the twentieth century; his questions were littered with references to, at least what Steur saw, their lack of understanding–“Do I make myself clear to you?”, “Do you understand me entirely?” (Transcript, 373). The defense attorney constantly repeated himself and asked the witnesses to go over details, again and again, highlighting their accents and potential inability to understand the defense attorney, who tried his hardest to talk around them and confuse them.

The biases against women, specifically young immigrant women, played a very important part in the defense’s case, especially in the face of an all-male jury. Throughout the trial, Steur cast doubt on the women’s ability to correctly open the door, implying that even if it had been unlocked, they may potentially have not been able to open it anyway. He asked eighteen year old Ida Nelson if she was even aware of what a [door] handle was to which she responded, succinctly: “I know” (Transcript 392). In his cross-examination of Ethel Monick, who had worked at Triangle for three months at the time of the fire, Steur placed more trust in a man attempting to open the door than any of the women working on the ninth floor: “Tell me then, did a man run over there and bang on the door and pull at the door and try to open it, did you see them?” (Transcript, 526). To interrupt the sexist line of questioning, Bostwick went as far as asking witness Ethel Monick to step down and show the court how she was capable of opening the court door, in an attempt to let the record show that the “witness took hold of the handle of the door, and in the presence of the Judge and jury tried to push and pull the door after turning the handle” (Transcript 486). Steur’s attempts to undermine the young women’s abilities continued throughout the trial.

Similarly, Steur worked hard to strike any emotion that the women expressed on the stand from the record, attempting to eliminate any empathy that the jury may have felt upon hearing their experiences. However, Steur did point out, multiple times, the panic that the women on the ninth floor of Triangle experienced during the traumatic fire, coloring it as a reaction that clouded their judgement and sent them into hysterics. In his opening statement, Steur stated that, even though “the door was wide open” (engulfed in flames, though he left this out), a policeman “saw two girls in the excited condition that were attempting to leave the building by jumping out the window” (Famous Trials). He continued, pointing additionally to the ‘excitement’ of the women as the reason they could not calm down and open the door correctly, therefore saving their own lives (Transcript, 526).

Judge’s Remarks and Trial Outcome

Before the jury deliberated, the Judge of the criminal trial left them with advice, which conceivably swayed the jury toward a verdict of non-guilty. His exact words were reported in the Literary Digest’s article “146, Nobody Guilty,” which was published the following day:

“Because they are charged with a felony, I charge you that before you find these defendants guilty of manslaughter in the first degree, you must find this door was locked. If it was locked and locked with the knowledge of the defendants, you must also find beyond a reasonable doubt that such locking caused the death of Margaret Schwartz. If these men were charged with a misdemeanor I might charge you that they need have no knowledge that the door was locked, but I think that in this case it is proper for me to charge that they must have personal knowledge of the fact that it was locked” (Cornell University — ILR School).

The specificity of the judge’s remarks sparked outrage. Jurors, such as Victor Steinman, admitted to being swayed by his words: “because the judge had charge us that we could not find them guilty unless we believe that they knew the door was locked then, I did not not know what to do” (Cornell University — ILR School). The jury absolved the Triangle owners of all charges. Harris and Blanck recovered $64,925 in insurance, ultimately clearly a profit of $445 per worker killed in their factory’s fire (McEvoy, 641).