“The disaster could have been prevented––not by a tanker captain and crew who are, in the end, only fallible human beings, buy by an advanced oil transportation system designed to minimized human error.”

– Walter B. Parker, Chairman of the Alaskan Oil Spill Commission (AOSC).

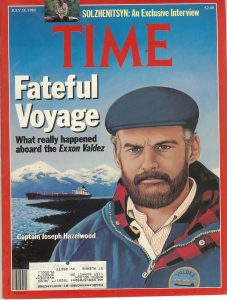

Two days after the grounding of the Exxon Valdez, the National Transportation Safety Board reported that the captain of the Exxon Valdez was legally drunk when he was tested some 10 hours after the incident. Following the news, Exxon immediately fired the captain and the media quickly picked up the story. Over the next couple of weeks, the “drunk captain” story dominated the media’s narrative of culpability.

This section examines the media coverage of the disaster by analyzing two separate newspaper articles: “Valdez Captain Turns Himself In: Bail Set at $500,000 for Charges from Alaska Oil Spill” (Los Angeles Times) and “Taking Risk on Rehabilitation: Tanker Spill Points Up Difficulties in Aiding Troubled Employees” (Washington Post). These two articles display how the media focused on Captain Hazelwood’s intoxication, thereby diverting attention away from the structural issues of the oil transportation system that allowed Hazelwood’s drinking and other human errors to result in an accident. Furthermore, the “drunk captain” narrative is problematic because it deflects blame away from Exxon, Alyeska, and government agencies whose decisions in the years leading up to the disaster contributed to the creation of such structural issues.

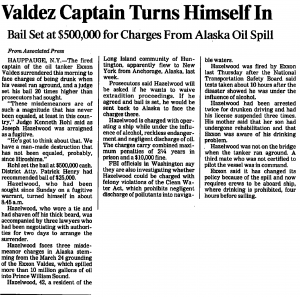

On April 5th, 1989, the Los Angeles Time published an article, “Valdez Captain Turns Himself In: Bailed Set at $500,000 for Charges from Alaskan Oil Spill,” that directly attributed blame on Hazelwood. In the opening lines, the article claims that Hazelwood “surrendered to face charges” for misdemeanors that according to the judge “were of such a magnitude that they have never been equaled, at least in this country.” The article’s usage of the word “surrendered” to described Hazelwood’s decision to turn himself in to face charges implies guilt, wrong doing and does not take into account the fact that Hazelwood denied being impaired during the night of the accident. Furthermore, the comment about Hazelwood’s misdemeanor––operating the ship while under the influence––places the blame of the accident on Hazelwood’s decision to break the law, ignoring the myriad of errors and actors that were also involved in the disaster. For instance, the article does not mention that at the time of the accident the ship was being navigated by a sober third mate and was being tracked by the Coast Guard’s monitoring system––information that was available when the article was published. By not addressing such complexities, the article presents a simplified and inaccurate narrative. This simplification is also seen in at the end of the article, where it states that Exxon in an attempt to mitigate future problems has created a new policy that requires crew members to be “aboard ship, where drinking is prohibited, at least four hour before sailing.”

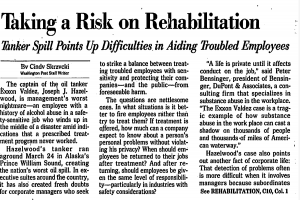

In “Taking a Risk on Rehabilitation,” The Washington Post also presents a “drunken captain” narrative of the disaster, yet in a different manner. Unlike the LA Times’ article which describes the Exxon Valdez accident as man-made and the result of crime, The Washington Post portrays the accident as a “tragic example of how substance abuse can cast a shadow on thousands of miles of American waterways.” According to the article, the Exxon Valdez disaster was the product of overly generous corporate managers who allowed Hazelwood, a man with a history of substance abuse, to return to his position after undergoing rehabilitation. As the article points out, “just because you go in for treatment doesn’t mean you are cured.” Yet, while Hazelwood’s history of substance abused might have been a red flag, the conclusion and narrative that the article provides is misleading and dangerous. Just like the LA Times article, this article kept the public scrutiny away from more important contributing factors, such as the lax maritime transportation system and Exxon’s toxic work environment; by elevating the role that Hazelwood’s drinking a played in the disaster. Furthermore, by labeling the disaster as a tragedy, the article portrayed the accident as inevitable and obscured the fact that the disaster was preventable.

Media coverage has a tremendous power to shape the way the disasters are remembered. This was especially true during the late 80s and 90s, a time period when newspapers and broadcasting news were the main way by which people across the U.S. and the world at large consumed the news. As such, the media coverage of the Exxon Valdez disaster provided the public with a narrative that was simplified and did not fully capture the whole story. While the mainstream media held Exxon and Alyeska responsible for their failed clean-up responses, the media did not do the same when assigning the blame for the grounding. The media’s “drunk captain” narrative, both the crime and tragedy versions, shined the spotlight on Hazelwood and deflected attention away from the structural system of corporate pressure and inadequate oversight that facilitated the human errors that led to Exxon Valdez grounding on the morning of March 24th.

Sources for Images (from the order in which they appear left to right):

-

Image of Captain Hazelwood arrest (getty images). Los Angeles Times (1923-1995); Mar 31, 1989; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Los Angeles Times.

- The Hartford Courant (1923-1995); Mar 31, 1989; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Hartford Courant.

- Times Magazine Cover; July 24th , 1989; Times website.

- Los Angeles Times (1923-1995); Apr 5, 1989; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Los Angeles Time.

- The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Apr 6, 1989;ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- Newsy LLC; Getty Images.