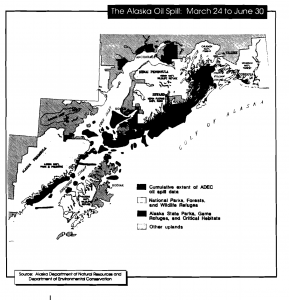

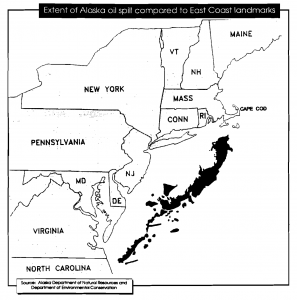

The consequences that the different communities and individuals faced in the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez disaster were not uniform. While the oil spill caused long-term social, psychological and cultural hardship for many individuals, for others it brought economic fortune and social mobility. This section examines the differential effects of the Exxon Valdez disaster by examining its impact on three distinct coastal communities: Valdez, Cordova, and Port Graham. The long-term impact that the disaster had on these communities illustrates how the spill disproportionally harmed native and fishing communities, like Port Graham and Cordova, respectively. These communities were especially vulnerable to the effects of the oil spill because of their reliance on the renewable resources of the land––resources on which their communities’ cultural, social, economic existence dependent upon.

Valdez: Home of the Spillioners

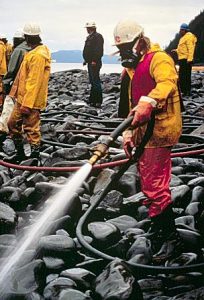

At the time of the disaster, Valdez was home to the Valdez oil terminal, the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company (the largest employer at the time), the regional airport, and the regional Coast Guard station. Given that Valdez was the most developed area in the region, it became the epicenter of the cleanup response efforts in the aftermath of the disaster. As a result of this, in the months following the disaster Valdez experienced an influx of specialists, bureaucrats, biologists, media reporters and out-of-town regional cleanup workers which led the town population to increased five-fold. While this population influx placed a strain on the town’s public resources, it also provided financial opportunities. For many of the local residents, the clean-up effort brought an influx of money that supercharged the local economy and lead to the rise of the so called “spillioners” ––local residents who financially profited from the oil spill clean-up efforts. For instance, during this time period, hotel, motel, and camper park owners doubled their rates, and remained full despite being in the off-season. Restaurant and shop owners also benefited from the increased demand. Yet, within the town of Valdez, not all locals benefited from the surge of people. As the Valdez mayor concluded “if you were on a fixed income in the city of Valdez, all of the suddenly you couldn’t afford to live” (ASOC, 82). Furthermore, during this period, the town crime rate spiked 300 percent and access to health care services became more challenging. At the aggregate level, the town of Valdez, which prior to the disaster had profited from the oil transportation business, thrived in the aftermath of the oil spill.

“Hey Bobby! What are you doin’ here? I thought you’d be up in Prince William getting fat on an oil spill contract?”

“Nah, I am a fisherman, not an oil company jockey.”

“I’m with you Bobby, I don’t think I can take their dirty money.”

-Conversation between two fisherman in Cordova. May 1989 (Day, 275).

Cordova: The Fishing Village

Cordova is a small fishing town about 45 miles north of Valdez. While the oil from the spill never reached Cordova’s shores, the spill had a dramatic long-term impact on Cordova and its community of fishermen/women. By harming the Sound’s fisheries and marine ecosystem in both the short and long-term, the spill destroyed the livelihood of this fishing community. In addition to causing economic problems, the decline of the salmon and herring fisheries caused the Cordovan community chronic stress. In the long-term, as fisherman lost their ability to fish and make a living off their boats, they often lost their sense of purpose and struggled with depression. According to a sociological study, in the aftermath of the Exxon spill the rates of “alcohol, drugs and spousal abuse, suicide and other related problems” among Cordovans drastically increased (Haycox, 229). Furthermore, the clean-up effort also increased animosity in Cordova between community members who choose to work for the Exxon cleanup effort and those who refused to on ideological grounds. It is estimated that around 60 percent of town residents in Cordova became advisors to the Exxon clean-up effort and were handsomely rewarded. This division harmed the social cohesion of the community which prior to the disaster had been extremely close nit causing further stress among the community members.

“Our elders feel helpless. They cannot work on cleanup. They cannot do all the activities of gathering food and preparing for winter. And most of all, they cannot teach the young ones the Native way. How will the children learn the values and the ways if the water is dead? If the water is dead, maybe we are dead––our heritage, our tradition, our ways of life and living and relating to nature and to each other.”

-Port Graham Chief Water Meganak Sr. (SPILL: The wreck of Exxon Valdez, 89).

Port Graham: A Native Village

Port Graham is a small native village that relies on traditional foods from the sea and is about 150 miles away from Valdez. The Exxon oil spill disproportionally harmed the Port Graham community, whose lack of infrastructure and reliance on renewable resources from the land made it vulnerable. Unlike Valdez and to a lesser extend Cordova, Port Graham is a town that is hard to access––it can only be accessed by a seven-hour boat ride. As a result of this, Exxon did not start the cleanup process in Port Graham until late March when much of the oil had already been absorbed into the ecosystem and contaminated the food chain. This was problematic because the native village was fully dependent on the fish and wild animals that inhabited this ecosystem. Given their lack of other food sources, the community members of Port Graham continued to consume seafood and other foods that were contaminated. This caused many villagers long-term health problems, such as lung cancer and internal organ failure. The Exxon spill also harmed the social fabric of the Port Graham community, where prior to the disaster subsistence hunting, gathering, and fishing were “cooperative family activities, during which young people [learned] the skills and values needed to survive” (Raloff, 2). By taking those away, the spill hindered the ability to pass down their culture and heritage to the younger generations (Raloff, 1). Furthermore, native communities often feel deeply connected to the land they inhabit, seeing it as an extension of their bodies and soul––making the damage profoundly personal.