History of the South Fork Dam:

Johnstown, Pennsylvania was once described as the “busiest, richest little community in the world”(PA Inquirer, August 23, 1889). The small industrial city is located in the Great Lakes Region, which became an epicenter for United States manufacturing during the nineteenth century. An extensive canal and dam system was built to match the rapid industrial growth. This included the South Fork Dam, which was built just north of Johnstown in 1852. The dam fell into despair in 1857 and changed ownership multiple times. The owner at the time of the disaster was the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, an organization primarily comprised of wealthy business tycoons. They bought the dam in 1879 and transformed the area into a vacation spot (Coleman 2019). The South Fork Dam represented America’s remarkable manufacturing and technological progress throughout the 1800s, as well as the achievements of the industrial giants who dominated the late nineteenth century.

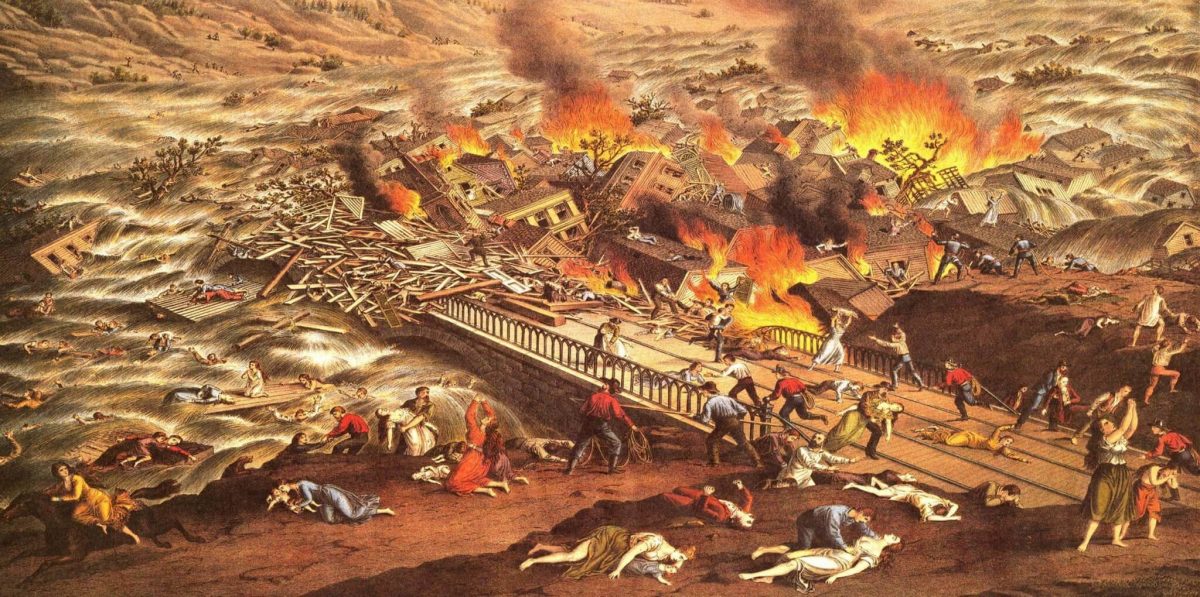

The Day of the Disaster:

At around 4:00 PM on May 31, 1889, this triumphant symbol came tumbling down. Following hours of heavy rainfall, the South Fork Dam failed. The water from the reservoir traveled fourteen miles to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, destroying almost everything in its path (Winklestein 2008). According to the South Fork Fishing Club ground superintendent, “Everything went before it like toys.” Twenty million tons of water rushed towards the city, forming a thirty-five-foot tall wall of water. A telephone operator at the South Fork Tower explained that the wave looked like “a mountain coming.” The wave accumulated so much debris that it seemed like “an avalanche of houses, water, trees, and freight cars” (Coleman 2019). Fires caused by overturned ovens and household appliances ravaged the debris, contributing to the destruction. Hundreds of people were swept away and those who remained had to watch their friends and family perish as they struggled to avoid drowning. Two train cars were even  swept off the tracks, killing everyone inside (Kansas City Times, 1889). Overall, the disaster killed over 2,200 people out of Johnstown’s population of 30,000. Though, it was difficult to determine exactly how many people died since the water carried many of the bodies away. One body was even recovered 100 miles away in Steubenville, Ohio (Coleman 2019). When it occurred, the Johnstown Flood had the highest death toll out of any previous U.S. disaster and is currently one of the top twelve deadliest floods of all time globally.

swept off the tracks, killing everyone inside (Kansas City Times, 1889). Overall, the disaster killed over 2,200 people out of Johnstown’s population of 30,000. Though, it was difficult to determine exactly how many people died since the water carried many of the bodies away. One body was even recovered 100 miles away in Steubenville, Ohio (Coleman 2019). When it occurred, the Johnstown Flood had the highest death toll out of any previous U.S. disaster and is currently one of the top twelve deadliest floods of all time globally.

Aftermath:

Johnstown was left in ruins. Debris and bodies were scattered everywhere, and the majority of the city’s buildings were damaged or destroyed. According to the Kansas City Times, all “but two houses could be seen in the town.” It was impossible to travel anywhere since all of the roads were ruined. This was detrimental to the victims who required immediate medical attention. Thieves took advantage of the vulnerable and the dead, though there was not much left to steal (Kansas City Times, 1889).

The Flood’s Impact:

Regardless of this success, the flood left a permanent impact on the United States’ collective memory. The disaster fascinated and horrified the public since Americans had never witnessed such a destructive and deadly disaster before. The grandiose nature of the disaster provided to be an ideal spectacle for the media to profit off of. For months after the flood, newspapers continued to cover Johnstown’s destruction and recovery (Coleman 2019). In addition, the legal context surrounding the disaster piqued the public’s interest. As discussed in the Avoidance of Blame section, the matter of assigning legal responsibility was contentious and gained a lot of media attention. Perhaps the primary reason why the Johnstown Flood made such a profound impact on the United States was due to the symbolic implications of the disaster. The contrast of such a triumphant symbol causing so much harm proved to be a very intriguing narrative. The public was captivated as an emblem of innovation and industry became the epitome of destruction and devastation.