JAHA Mission Statement:

“JAHA is dedicated to preserving and interpreting the nationally significant historic heritage of the Greater Johnstown Area through its museum facilities, historical collections, and education programs. JAHA operates as a clearinghouse and catalyst for revitalization efforts based on cultural tourism and historic preservation.”

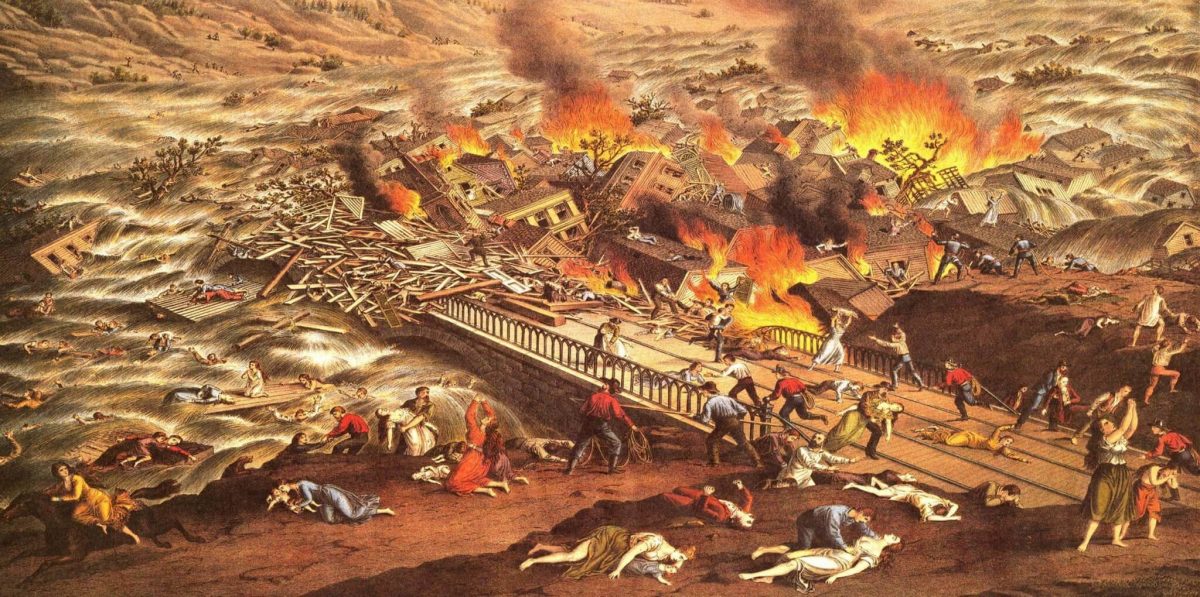

The Johnstown Area Heritage Association, or JAHA, was founded in 1971 to interpret and preserve the memory of the Johnstown Flood. In 1989, JAHA created an 1889 flood-themed visitor experience. They rebuilt buildings that were previously destroyed and created multiple films and documentaries to explain the disaster. In 2009, JAHA even opened a Johnstown’s Children’s Museum and five years later, they created the People’s Natural Gas Park which is used for concerts, weddings, and other events.

The ethics of such an organization are contentious. JAHA is a non-profit organization, so a business is not capitalizing on the disaster. Also in JAHA’s favor is that it is a local organization commemorating its own history. If a larger organization like the Smithsonian was to create a museum exhibit based on the disaster, especially if the exhibit was not located in Johnstown, it would lack the authenticity and intimacy that JAHA is able to achieve. Johnstown residents also might prefer for locals to profit off of the city’s traumatic history rather than a larger, distant organization. JAHA also claims that by creating the attractions, they bring visitors to the area that contribute to the region’s economic development through heritage tourism, therefore enhancing the quality of life of the locals. JAHA takes on more practical projects that extend beyond education as well, even refurbished the Johnstown Train Station in 2017. They are also involved in many historical research projects, allowing for a more accurate account of events to be uncovered. Perhaps JAHA’s most essential offering is that they maintain the archives that document the disaster, ensuring that its memory will not be washed away. All of these services are valuable, but the difficulty for an organization like JAHA is making the distinction between memorializing a disaster and profiting off of one.

The ethics of such an organization are contentious. JAHA is a non-profit organization, so a business is not capitalizing on the disaster. Also in JAHA’s favor is that it is a local organization commemorating its own history. If a larger organization like the Smithsonian was to create a museum exhibit based on the disaster, especially if the exhibit was not located in Johnstown, it would lack the authenticity and intimacy that JAHA is able to achieve. Johnstown residents also might prefer for locals to profit off of the city’s traumatic history rather than a larger, distant organization. JAHA also claims that by creating the attractions, they bring visitors to the area that contribute to the region’s economic development through heritage tourism, therefore enhancing the quality of life of the locals. JAHA takes on more practical projects that extend beyond education as well, even refurbished the Johnstown Train Station in 2017. They are also involved in many historical research projects, allowing for a more accurate account of events to be uncovered. Perhaps JAHA’s most essential offering is that they maintain the archives that document the disaster, ensuring that its memory will not be washed away. All of these services are valuable, but the difficulty for an organization like JAHA is making the distinction between memorializing a disaster and profiting off of one.

In general, disaster tourism induces concern. Many argue that viewing a disaster as a source of entertainment is insensitive to the victims no matter the tragedy. Disaster tourism is especially troublesome if it makes light of the tragedy that it claims to commemorate. Perhaps it is problematic that the JAHA Children’s Museum hosts birthday parties. Is it appropriate for a joyful event to take place at a location that experienced so much destruction and loss? JAHA also hosts multiple annual events that are named for the disaster. Every year, they organize a Flood City Music Festival in the Peoples Natural Gas Park. Originally, this festival was created to commemorate those who died in the flood. Locals came together and played music for the sake of community and healing. The tradition evolved over the years and eventually became more commercialized. Corporate sponsors became involved, artists and attendants came from all over the country, and ticket prices became more and more expensive. Eventually, people came to consider the Flood City Music Festival as a primarily recreational event no longer centered around the remembrance of the Johnstown disaster. Yet, the event still invokes the tragedy in order to entice audiences, even though the festival has little to do with the original disaster anymore. Perhaps even more problematic, JAHA hosts a Path of the Flood Historic Race every year. This event is more explicitly related to the disaster than the music festival, but that does not necessarily make it more respectful. Participants begin at the remains of the South Fork Dam and run the same path that the water traveled to end up in Johnstown. On JAHA’s website, they advertise the race as an “opportunity to ‘be the water’ as you face into the new trail and it’s steep initial eighty-foot ascent – forcing your way up and over the top, breaching the ‘dam’ and allowing your potential to shift into kinetic energy where you will roil and foam along this new 1.75-mile stretch.” Personifying the racers in this way is questionable since it could be considered making light of

the disaster. In 1889, the water that breached the dam was just as dangerous a weapon as any firearm or explosive. Yet, no organization would ever encourage people to imagine themselves as the bomb from the 2013 Boston Marathon or the bullets fired in the Las Vegas shooting. Though the water was not intentionally weaponized in 1889, it was still incredibly destructive and traumatic.

Reflecting on an organization like JAHA raises the question of why certain disasters are considered more serious than others. The Johnstown Flood is one of the deadliest U.S disasters of all time, yet it is still taken relatively lightly. Perhaps enough time has passed since 1889 that people have become desensitized to the flood. It also might be less of a taboo subject since the flood was an unintended accident rather than a preconceived plot. It is clear that in the United States, targeted attacks like terrorism are regarded as especially somber. Maybe Johnstown residents only allow the disaster to be taken lightly since they can profit off of it. There probably is not one right answer, but it is still useful to consider what aspects of a disaster qualify it to merit public sensitivity. JAHA probably has good intentions, or at least began with good intentions, but can it ever be ethical to profit from the spectacle of a disaster?

*all information comes from JAHA website (see bibliography)