The “Unsinkable” Ship that Sank

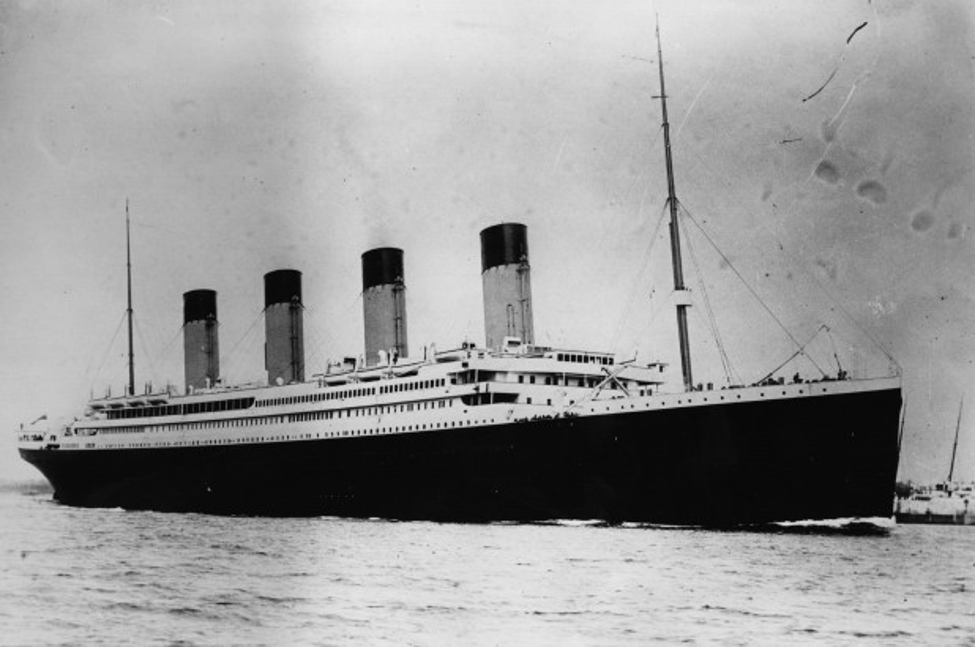

All Her Glory

The Titanic was the largest moving object on earth at the time it set sail on its maiden voyage in April 1912, making it the pride of the White Star Line. Not only was Titanic the largest ship of its time, however it was also the most luxurious and technologically advanced. If it wasn’t completely, “the ‘ship of dreams’ as mentioned in James Cameron’s blockbuster film, RMS Titanic was a mechanical work of maritime art” (Brown, McDonagh & Shultz, 2013, 598). It was a ship that was carefully crafted to accommodate up to 2,500 passengers “in three classes carefully segregated by price, luxury, and social caste,” (O’Neil, 2012, 1). While many people at the time asserted that the ship was “unsinkable” it is believed that the White Star Line never made this claim. Instead, a leading magazine “Shipbuilder” was the one that dubbed the ship, “practically unsinkable” as the ship was comprised of sixteen watertight compartments, and it was designed to stay afloat with four of the sixteen compartments flooded (O’Neil, 2012, 1). It was assumed that there would never be more than four compartments flooded, and therefore the media ran with the idea that the ship was “unsinkable.”

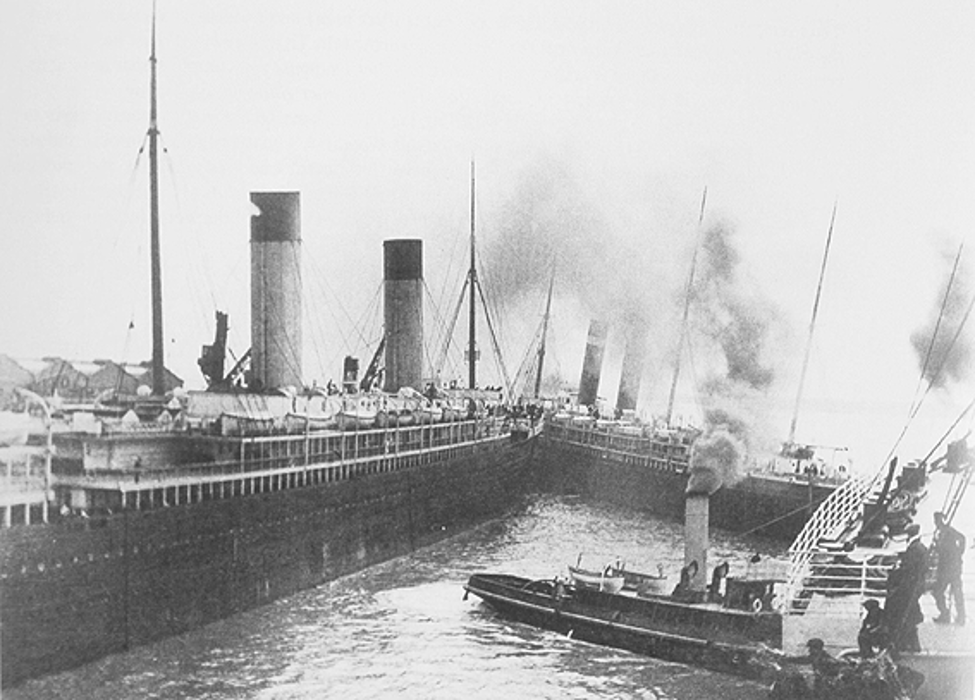

A Bad Omen

The ship left from Southampton, England on April 10, 1912, making two stops in Cherbourg, France and Cobh, Ireland before beginning its voyage to New York on April 11, 1912 with about 2,200 passengers and crew onboard. On April 11, 1912, the New York Times published an article that described an incident that took place as the Titanic left port in Southampton. As the Titanic headed for open seas, near disaster took place when her undertow pulled the S.S. New York from her hawsers and was quickly sucked towards the Titanic, where “for some time a collision looked likely,” (New York Times, 1912). Many deemed this incident a bad omen for what was to unfold on the Titanic just four days later.

Titanic in Distress

Four days into her journey, the Titanic continued at 22 knots which was just below top speed. April 14, 1912 was a particularly calm night, making icebergs incredibly difficult to see because there were no waves breaking on the ice to make it visible. The wireless operators had received at least six telegraph messages throughout the day warning of ice in the area. As the evening wore on, ice warnings continued to come in, however the wireless operators were backed up from passenger messages, and never relayed the later warnings to the bridge. The last ice warning came in at 11:00 pm from the Californian which informed the Titanic it was stopped for the night due to icy conditions, but this too was ignored. Forty minutes later, the lookouts saw an iceberg ahead and alarmed other crew members. First Officer Murdoch called for engine reversal, but it was too late. Thirty-seven seconds later, the Titanic struck the iceberg on its starboard side at 11:40 pm. Within minutes, six of the watertight compartments flooded, making it impossible for the ship to stay afloat. Frigid water began flooding the Titanic’s lower decks (O’Neil, 2012; Tikkanen, 2020).

The Final Hours

After the Titanic struck the iceberg, the ship builder Thomas Andrews estimated about one to two hours before it would sink. Around midnight on April 15, 1912, Captain Smith ordered the first distress calls to be sent, and lifeboats begin launching with women and children ordered to be put in boats first. The Carpathia was the only ship to respond to the distress signals, and it began its 58-mile journey to the Titanic, which would take over three hours to complete. Numerous rockets were fired, but none proved successful. With lifeboats for only 1,178 people, only half of the total passengers and crew on board its maiden voyage would have been accommodated for. Much worse, however, is that several lifeboats were lowered with less than half of their full capacity. Reasons for this ranged from interpretations of the “women and children first” orders given to the officers operating lifeboats, to passengers afraid of overcrowding the boats, to people refusing to board the boats at first because they believed it was impossible for the ship to sink. Around 2:00 am, the last lifeboat was lowered. About 15 minutes later, the final distress signal went out, just before the ship went dark. At 2:20 am, the Titanic reportedly split in two due to tremendous strain on the midsection of the ship. The bow sank first, followed by the stern’s final plunge. Only one lifeboat turned back for survivors who were in the water, with the rest fearing their boats would be swamped by swimmers. The Carpathia arrived at the scene around 4:00 am, where it would bring the mere 700 survivors to New York (O’Neil, 2012; Tikkaken, 2020; Levinson, 2012).

Inequality and Aftermath

The disaster caused a tragic loss of 1,500 passengers and crew members, however survival rates among the those on board shared in a clear pattern. Over half of the first-class passengers survived while only one quarter of third-class passengers and one fifth of crew members lived (O’Neil, 2012). The differences of survival rates along class lines clearly demonstrated the differential effects that the Titanic disaster endured. In the aftermath of its devastation, the Titanic stimulated British and American authorities to pass laws that required that all ships carry enough lifeboats to accommodate everyone onboard, lifeboat drills to be mandated, and lifeboat inspections to be conducted. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea was also created in response to the tragedy, and this conference resulted in international funding and support of the International Ice Patrol, which monitors the location of icebergs that threaten sea traffic (Levinson, 2012, 154).

Significance

The dominant “unsinkable” narrative that circulated both before and after the Titanic disaster made the sinking of Titanic particularly ominous. In a time where human technology was considered to have conquered all, the unwavering faith in technology was shattered when it went disastrously awry on April 15, 1912. This disaster, however, did not bring an end to this hubris belief in human capabilities. The “unthinkable” has continued to play out in modern disasters, as seen with the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster in 1986 where human technology once again failed in an unexpected and tragic catastrophe. In addition to the importance of memorializing those who perished aboard the Titanic, this disaster holds an important place in history that stands as a reminder of the fragility of human lives and human advancements, and therefore it should continue to be studied, discussed and remembered for years to come.