A Survivor’s Perspective of Responsibility

Complexity of Blame

There is never any one person or thing to blame in the context of disasters. While some subjects of blame may seem more obvious than others, it is impossible to determine just one factor that is completely responsible for the devastation in a given disaster, particularly because everyone has different ideas who or what is the culprit. The following section investigates the survivor’s perception of blame in the Titanic disaster.

A Survivor’s Account

Lawrence Beesley was a second-class passenger aboard the R.M.S Titanic and published his eye-witness account of its sinking just two months after the disaster in June 1912. His hope in publication was to provide an accurate account of the disaster in the midst of false information spreading through media at the time. He also hoped to bring awareness to the catastrophe in order to spark necessary reforms to prevent disasters like the Titanic in the future. Through his account, he called into question the dominant narratives of responsibility as he attempted to make sense of the complications of blame. In his analysis of blame, Beesley extended his scope of responsibility to include a range of people and entities, demonstrating the many ways he believed blame was shared across a wide sphere.

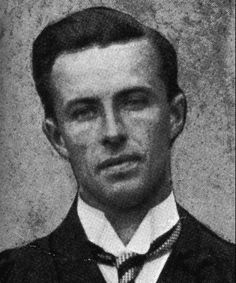

Titanic survivor and author of The Loss of the S.S Titanic It’s Stories and Its Lessons. “Titanic Survivor Lawrence Beesley.” Digital Image. Titanic Universe.

Captain E.J. Smith:

As the Captain of the Titanic, many people point to E.J. Smith has the immediate subject to blame for the 1912 disaster. After all, it is the captain’s duty of the ship to navigate the correct course, set the designated speed, appoint the correct number of lookouts, respond timely to warning calls, and ensure the safety of all passengers and crew members. While Captain Smith certainly held significant responsibility due to his specific duties of overseeing all of the ship’s operations, the assertion of blame in the wake of disaster is never straightforward.

Lawrence Beesley was aware of the complicated and impossible process of assigning blame and therefore he saw several faults in shouldering the fault on Captain Smith entirely. Instead, he claimed, “Every captain who has run full speed through fog and iceberg regions is to blame for the disaster as much as [Smith] is: they got through it and he did not.” (Beesley, 1912, 235-236). While Captain Smith was responsible for the decisions he made when navigating the dangerous conditions on the night of the disaster, Beesley asserted that it could have been any other liner to strike an iceberg as the Titanic did because many other captains would have likely done the same in Smith’s position. With all of the uncertainty and chaos at the time, Beesley questioned the claim that Smith held complete responsibility, instead expanding the scope of blame to others.

Corporations

Beesley explained that blame could easily be stretched to the White Star Line and Harland and Wolff, which were the companies that owned and built the Titanic, respectively. According to Beesley, “The White Star Line has received very rough handling from some of the press, but the greater part of this criticism seems to be unwarranted and to arise from the desire to scapegoat. After all they had made better provision for the passengers the Titanic carried than any other line has done, for they had built what they believed to be a huge lifeboat, unsinkable in all other ordinary conditions” (Beesley, 1912, 240). In this sense, while the ship was an entirely manmade piece of material, the iceberg it struck was a natural force. Beesley saw the companies that others deemed responsible for the disaster as part of an extraordinarily unfortunate event that they were unprepared for. Instead, their preparations protected them against “ordinary” conditions, and unfortunately, there was nothing ordinary about the night the Titanic sank.

To many, the Titanic was thought of as “unsinkable” such that when disaster struck, several passengers chose to stay inside the warm, dry ship rather than making way into cold, dark lifeboats. In his eyewitness accounts, Beesley claimed he observed minimal panic on deck due to the pervasive idea of the “unsinkable ship.” He stated, “while the theory of the unsinkable boat has been destroyed at the same time as the boat itself, we should not forget that it served a useful purpose on deck that night—it eliminated largely the possibility of panic, and those rushes for the boats which might have swamped some of them (Beesley, 1912, 241). Rather than blaming the White Star Line, Harland and Wolff, and the media for this utterly false narrative, Beesley saw it as somewhat of a blessing in disguise rather than a source of blame.

More recent evidence, however, suggests it was unfair to assume the Titanic was practically unsinkable in “ordinary conditions.” A 1998 article in the New York Times discussed research on recovered rivets from the hull of the Titanic which disclosed issues in the quality of the ship’s construction. The structure of the ship was held together with millions of wrought iron rivets to which the article claimed, “The microstructure of the rivets is the most likely candidate for becoming a quantifiable metallurgical factor in the loss of the Titanic.” (Broad, 1998, 5). While investigating the quality of rivets in modern times suggests that Beesley was wrong in his assessment of the “unsinkable” ship, his argument held true based on the knowledge that he and others had at the time.

Public Demand

The context of the Titanic disaster is important because it occurred at a time in which companies were competing to be proud owners of the largest and most luxurious of their time, all of which was driven by public demand, as this was the very context in which Beesley wrote his book. Beesley argued the scope of blame should be expanded to include this public demand and wrote, “What the public demanded the White Star Line supplied, and so both the public and the Line are concerned with the question of indirect responsibility,” (Beesley, 1912, 237). The role of the media is also included in this aspect of blame, as advertisements included promises of making the transatlantic journey in just a few days such that liners had to, “go full speed nearly all the time.” (Beesley, 1912, 236) Beesley went so far as to assert, “all of us who have cried for greater speed must take our share of the responsibility.” (Beesley, 1912, 239). The idea of blaming everyone who wished for faster ships is one that perhaps more is far-fetched, simply because these demands were likely unconscious tradeoffs for safety. This concept of blaming individuals with no direct connection to the disaster itself can be hard to fathom, but valid, nonetheless. Beesley’s assessment of blame in this sense also contributed widely to the sense of shared responsibility for the disaster.

Government(s)

As with every disaster, blame can always be traced back government(s). While the Titanic “complied to the full extent with the British government” (Beesley, 1912, 243) in terms of lifeboat and inspection requirements, there were no speed or communication regulations for dangerous conditions at sea. To this, Beesley proposed, “The regulation of speed in dangerous regions could well be undertaken by some fleet of international police patrol vessels, with power to stop if necessary, any boat found guilty of reckless racing” (Beesley, 1912, 246). Not only did Beesley attempt to extend blame for the disaster across the global stage, however, he also extended the responsibility to international governments in order to prevent future maritime disasters. Along with this, Beesley proposed that blame will continue to be shed on governments in future maritime disasters until precautions are taken in response to the Titanic tragedy. Therefore, his analysis of blame even expanded past the 1912 disaster and looked into the future in hopes of preventing similar catastrophes.