Differential Effects of the Disaster

Differential effects are present in every disaster, and the Titanic was not exempt from its own share of disproportionate burdens placed on certain groups of individuals. Socioeconomic status, for example, plays a key role in the outcome of several disasters, including in the Titanic. Whether it be that those with more socioeconomic power can afford to build their homes on more stable land to protect against earthquakes, or that they can afford to escape a flood zone in the wake of a tsunami or hurricane, or the fact that they simply have access to better care and priority in rebuilding processes, it is no secret that class has clear implications in times of crisis. Since everyone onboard the Titanic was physically in the same location, the nature of differential effects was different than other disasters where certain people are able to escape the catastrophe. This is not to say, however, that differential effects did not exist, but rather that they prevailed in terms of chances of survival, access to information and lifeboats, and even in the collection of bodies in the aftermath. This had implications most obviously in survival rates, but also in terms of social norms and movements in the Titanic’s wake.

Likelihoods of Survival

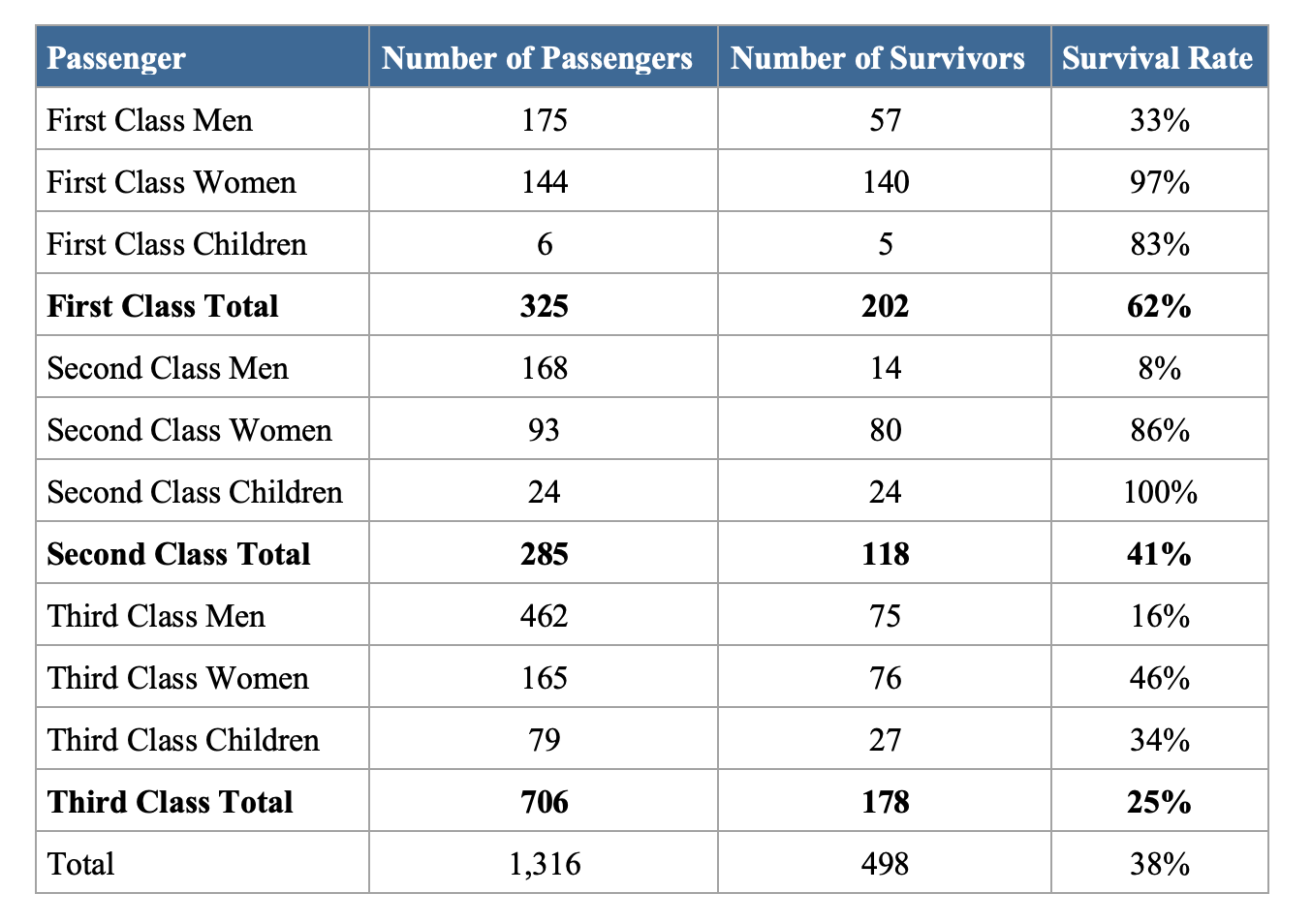

There is no doubt that class, gender, and age played a huge role in passengers’ likelihood of survival. Table 1 illustrates the survival rates from the Titanic disaster as a function of class and gender/age. First class passengers had the highest survival rate at 62 percent, followed by second class at 41 percent, and third class at 25 percent. Women and children survived at rates of about 75 percent and 50 percent respectively, while only 20 percent of men survived (Takis, 1999). The role of class such that first-class passengers had the best chance of survival, followed by second- and third-class passengers was not necessarily surprising.

Table 1. Likelihood of survival based on class and gender. Raw data from Takis, Sandra L. “Titanic: A Statistical Exploration,” 1999.

Information and Lifeboat Access

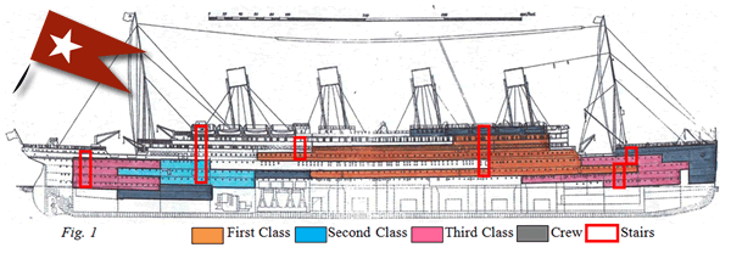

Socioeconomic status on the Titanic created critical boundaries between first-, second-, and third-class passengers. In terms of the physical space that was occupied by each class of passengers, first- and second- class cabins were much closer to the boat deck (where the lifeboats were located) than third class passengers (see Figure 1) (Frey, 2011, 2015). First- and second-class cabins were primarily separated by purely social barriers whereas physical gates separated the third-class quarters from other areas of the ship (Levinson, 2012, 151). This of course, made accessing lifeboats much easier for first- and second-class passengers, as time is of the essence on a sinking ship. However, access to lifeboats was not the only type of access that favored upper classes. Access to information was widely dispersed, but information access tended to be separated along class lines. Since lifeboats were in close proximity to upper-class cabins, these passengers were better able to see firsthand the severity of the situation. Those in first class also were advantaged in the sense that they had more connections to crew members (many of whom congregated for an elegant dinner amongst first-class elites and top crew members just a few hours prior to the collision) and they were able to gain access to information through these connections (Frey, 2011, 215).

Figure 1. Cabin locations and access to lifeboats based on class. Woolley, Joe. “Class segregation on board RMS Titanic.” Digital Image. Encyclopedia Titanica.

Pervasiveness of Inequality

Differential effects on the Titanic did not cease to exist after her final plunge. After the ship sank, the Mackay-Bennett sailed around the scene, to pick up floating corpses. The bodies of first-class passengers that were recovered were placed in coffins on the main deck, while the bodies of second- and third-class passengers were put on ice in the hold in sewn-up canvas bags (Levinson, 2012, 151). This is similar to the aftermath of many disasters, in which effects of socioeconomic status persist even after the loss of life, which is not to say it makes it any easier to comprehend.

Social Norms and Movements

Rather than spatial location and access to information, the differential outcomes in terms of gender and age could be widely attributed to the social norms that were strictly followed on the night of the Titanic disaster, all the way through its very last moments. In situations of life and death, a widespread social norm is that the safety of women and children should be prioritized (Frey, 2011, 216). On the Titanic, Captain E.J Smith gave specific “women and children first” orders to the first and second officers (each of whom was responsible for filling lifeboats). Officer Lightoller, on the port side of the ship, took this order to mean women and children only, resulting in lifeboats being lowered prior to reaching full capacity. On the starboard side of the ship, Officer Murdoch interpreted the orders as they were stated, meaning that men were offered seats on lifeboats so long as there were no women and children waiting to board (Levinson, 2012, 149). In either case, established social norms that defined women and children as vulnerable, weak, and in need of protection were honored by most men even when faced with imminent death. Thus, the pervasiveness of these norms was a driving factor behind the disproportionate number of deaths suffered across age and gender. As a consequence of how social norms played out in disasters such as the Titanic, fighting for women’s rights during the suffrage movement was even more difficult. As women fought for independence and voting rights, their voices seemed less legitimate when most women accepted the “women and children first” rule without question when onboard the Titanic (Levinson, 2012, 149).

In Conclusion

The sinking of the Titanic was similar to many disasters in the sense that certain groups were disproportionately burdened with the tragedy. A striking and direct link between class and gender to the likelihood of survival in the Titanic disaster, however, was fundamental to the outcome of the event, so much so that people’s lives quite literally depended on these two characteristics. Several factors and decisions accounted for these differential effects including unequal access to information, social norms, as well as the division of cabin locations along class lines. While “differential effects” in the case of the Titanic really just came down to who was given the choice of survival or not, they did go on to have consequences in later movements, such as in the United States’ and Britain’s women’s suffrage movements less than a decade later.