The Difficulties and Dangers of Communication in Crisis

Introduction:

Communication in any disaster is difficult for myriad reasons, and often it can be the key difference between life and death. Particularly in 1912, with radio communication only in its formative years, it is no wonder that communication was a key hardship in the events that unfolded the night of the Titanic’s sinking and in the days following the tragedy. Not only was the communication—or lack thereof—on the Titanic difficult due to temporal and technological constraints, however it also proved to be extremely dangerous as demonstrated by the tremendous loss of life.

Difficulties of Communication

Communication has transformed entirely from the wireless telegraph system that was used aboard the Titanic to the insurmountable types of instant communication we use today, making communication more than a century ago extraordinarily more difficult than its modern form. Published newspaper articles on April 15, 1912 (the day that Titanic sank) demonstrate the extent of communication difficulties of the time period clearly. Several newspapers published false headlines that claimed that all passengers were saved, and the Titanic was being pulled to shore, most likely due to the garbled telegraph messages of the time (Levinson, 2012, 145). One of these articles, entitled “All People on the Steamship Titanic Are Safe” published the claim that the passengers were “being transferred to the steamer Tarpathia.” (Evening News, 1912, 1). While this claim likely originated from a garbled telegraph (given the actual steamer that rescued survivors was the Carpathia), others could not be attributed to simply distorted signals. Another article published on April 15, 1912 from the Kansas City Star entitled, “Safe Off Titanic” described a completely fictitious outcome of events. This paper stated that the Titanic’s watertight compartments held after the collision, “However, the fight was too much for the proud ship and Captain Smith reluctantly permitted the Virginian to pass him a hawser and help his water heavy craft toward shore.” The article described further that three other ships arrived to help the distressed Titanic, however, “their aid was not needed. The passengers were transferred safely on a calm sea.” (Kansas City Star, 1912, 1). Clearly communication at the time that the Titanic sank was difficult due to the technological constraints of the telegraph. The signal was easily distorted and at times was difficult to understand. However, communication was evidently difficult beyond just the technological limitations of the time. In times of disaster especially, lines of communication are not always clear, and there is often not enough time to relay transparent messages and confirm sources. In this case, completely false narratives emerged in newspapers all over the globe on April 15, 1912, which spread false hope to many that their loved ones would return home from the Titanic’s maiden journey.

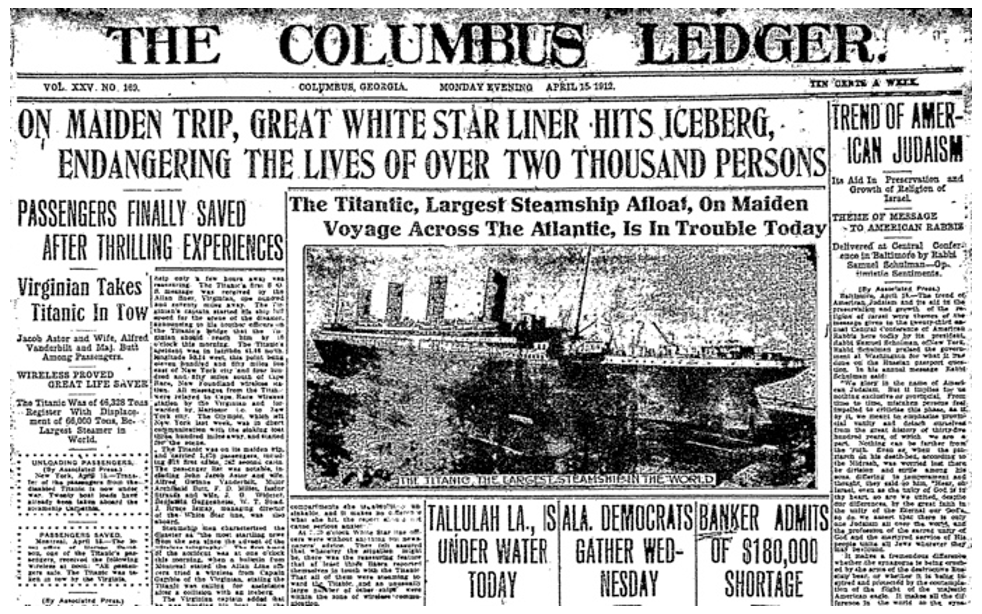

The Columbus Ledger Headline. April 15, 1912. Notice “Wireless proved great life saver” on left column.

Dangers of Miscommunication

Not only is communication difficult, but miscommunication can be extremely dangerous, and this was certainly the case in the Titanic disaster. Communication on board the ship itself was just as complicated as telegraph messages sent to media sources, however it proved much more dangerous than any misreporting in news outlets. The wireless operators on board the Titanic were responsible for relaying messages to the Captain and officers on the bridge, “But their chief devotion was to their employer, Marconi International Marine Communication Company Limited, an outfit that made most of its profits from sending Marconigram messages of the ‘Having a wonderful time, wish you were here’ variety,” (Levinson, 2012, 152). This contributed to at least four warnings of ice from ships in the area between 9 am and 1:45 pm not being properly transferred to the officers navigating the Titanic. At around midday on April 14th, the wireless stopped working which took nearly seven hours to be fixed. Once it was finally working again, the system was backed up and the operators were overwhelmed with passenger messages. Therefore, ice warnings in the evening and into the later hours of the night were also not transferred to the bridge as they should have been (Levinson, 2012). A particularly important message that had been missed was from the Mesaba, which warned of a dangerous ice field in the Titanic’s surrounding area. “Had Captain Smith known of that warning, which contained a detailed reading of the dangerous ice conditions in the area surrounding the Titanic, he might have considered changing course or reducing speed.” (Levinson, 2012, 152). Another warning which came in one hour before the Titanic’s deadly ice collision from the Californian was once again not communicated properly to Captain Smith, “which was most unfortunate because if heeded it could have prevented the Titanic’s sinking,” (Levinson, 2012, 152). The idea that something as simple as relaying messages could have saved the lives of nearly 1,500 people is bleak and troubling, however miscommunication is perilous in any disastrous situation.

Dangers and Difficulties

Communication demonstrated its both difficult and dangerous qualities on the Titanic when it came to lifeboat protocols especially. Upon the command to begin lowering lifeboats, Captain E.J Smith gave specific “women and children first” orders to each of the officers that were responsible for filling lifeboats. Officer Lightoller, on the port side of the ship, took this order to mean women and children only, resulting in lifeboats being lowered prior to reaching full capacity. On the starboard side of the ship, Officer Murdoch interpreted the orders as they were stated, meaning that men were offered seats on lifeboats so long as there were no women and children waiting to board (Levinson, 2012, 149). Since the order from Captain Smith had multiple interpretations, this led to the launch of several lifeboats that were only partially filled. Although the lifeboats had the capacity to accommodate upwards of 1,100 people, only 700 actually survived. While the 400 people who perished due to partially filled lifeboats may not be fully attributed to misinterpretations of orders, perhaps more clear communication could have saved many. There was, however, tremendous stress and pressing time constraints in the ship’s final hours that made communication difficult. While both officers took different approaches to interpreting orders, they were likely each doing what they felt was most appropriate at the time. The difficulties of interpreting and acting on information effectively, however, is never simple in times of crisis and therefore proves extremely dangerous.