Following the disaster on March 25, 1911 was an outpour of support that surrounded the surviving girls and the victims’ families from all over the city, the nation, and even around the world. Within twenty-four hours of the disaster, over 200,000 New Yorkers traveled to view the caskets of the victims and pay homage to those killed.

Within the immediate aftermath of the fire, two class-based organizations appeared, looking to address what they viewed as the most important issues following the Triangle factory disaster. Working class labor unions, as seen with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), provided aid for workers and their families, yet also hoped to push the public to see the Triangle fire as a disaster that could be avoided should labor reform be enacted swiftly. On the other hand, the Organization of NY (COS) and the Red Cross, which consisted of mainly middle class membership, hoped to provide aid for victims and affected communities, yet did not view the fire as anything short of a natural disaster, therefore refusing to acknowledge the rampant problem of unsafe labor conditions in early 20th century. These relief efforts, though seemingly hoping for the same thing, showcase the ways in which “class, cultural, and political boundaries” were exacerbated within the Triangle fire aftermath and response (Todd, 65). In fact, they exemplify the two plausible, yet contradictory, ways of observing disasters: the union organizations saw the fire as an instance of slow violence that would only happen again if those to blame were not held responsible and stopped, while COS and the Red Cross saw the tragedy at Triangle as a one off, spectacle disaster, that did not warrant any further action beyond charity for the victims.

Organizations such as COS and the Red Cross, whose membership consisted entirely of middle class white women, were horrified at the disaster at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Immediately they began to gather funds from New York City’s large charities and businesses, such as The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, to aid the victims of this “natural disaster” (Greenwald, 69). They reached out to powerful organizations, as well as politicians: Mayor Gaynor, for example, pleaded for donations on behalf of the organization in all major papers in the city. The Red Cross Committee consisted of a small crew of workers, most of whom were members of The New York Society for Improving the Condition of the Poor. Together, the organization illustrated perfectly the way in which they pushed for charity on behalf of the ‘poor’ spectacle disaster victims and their struggling families, yet did nothing else to improve the situation of vulnerable working class communities all over the city and country.

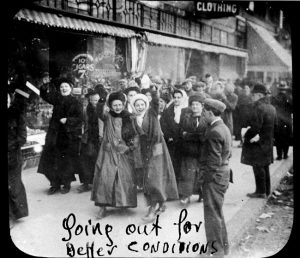

On the other hand, union groups, such as ILGWU, had had their sights on the unionization of The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory long before the disaster. In 1909, 20,000 shirtwaist makers in New York City walked out of 500 different factories, taking part in a major strike organized by ILGWU that was aptly named the Uprising of 20,000. The strikers demanded a pay increase, reasonable hours and extra pay for overtime; they also called for updated safety measures, including unlocked doors during factory hours, as well as adequate fire escapes (Dreier, 31). Several months into the strikes, many of the smaller sized shirtwaist factories conceded to the demands. However, Harris and Blanck–also known as the “shirtwaist kings”–were adamantly anti-union and capable of withstanding the calls for labor reform by their employees, instead relying on police and legal disputes to break up the strikes (Dreier, 31). Therefore, the Triangle workers returned to the sweatshop after the Uprising of 20,000, unsuccessful in their requests for safer, more humane working conditions.

ILGWU had worked with the Triangle workers during the Uprising of 20,000; many of the members of ILGWU had also been victims to unjust working conditions in garment factories, as well. So, when they were not only unable to unionize the young immigrant workers at Triangle in 1909, but also had to watch as so many of them perished two years later due to unsafe working conditions, ILGWU immediately sprung into action. Following the fire, The Relief Fund Committee–originating from the Ladies Waist and DressMakers’ Union, a local section of the ILGWU–began spreading the news of the disaster, buying articles in labor and left-winged newspapers, and fostering just outrage throughout the city (Greenwald, 67). Their goals were two-fold: aid the families and victims with money raised from “unions, various socialist and reform-minded groups, philanthropists, theater groups and reform organizations,” and build a “new world order” that furthered issues of social justice, as well as labor reform to prevent such a disaster from happening in the future (Greenwald, 68-69). ILGWU, which consisted of working-class garment workers themselves, was far more cognizant on the overall issues that caused the Triangle Fire and comparable industrial disasters; where COS and the Red Cross saw it as an accident, a slip of a cigarette onto some flammable fabric, ILGWU saw it as malicious on the end of business owners, as well as a lack of political intervention.

Workers of this era were apprehensive of charity, which was often construed as a handout, so reactions from the surviving Triangle victims toward the unions were far more positive than the middle-class charitable organizations, for they had a say in building the working-class labor movement that the unions fostered. In the words of Rose Schneiderman, an immigrant factory worker and leader of the Uprising of 20,000: “I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement” (Greenwald, 74). In other words, reformers–such as COS and the Red Cross–would simply hand out one-time donations, and maybe slightly alter laws, while maintaining the oppressive, structural oppression that lay beneath them. An entire overhaul of the industrialized labor system was needed to make a difference, and this came from working-class pushes for unionization.

Even though the two organizations, at least on the surface level, both wanted relief for Triangle victims and their families, they differed greatly when it came to what exactly they were providing relief for, a one-off incident or a long series of injustices and slow violence. Tensions between these two distinct camps of relief provision rose to a premium at a cross-class meeting, which took place in the week following the fire at the Metropolitan Opera House as an “attempt to find common ground in relief” (Todd, 66). Little compromise was possible, as all middle-class attempts at reform did not include labor unions. Ultimately, Rose Schneiderman, a labor unionist herself, intervened with a memorable quote that illustrates how the unions saw themselves and their causes in comparison to middle-class, less-revolutionary organizations:

“I would be a traitor to those poor burned bodies if I were to come here to talk good fellowship. . . . We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers and brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable, the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us….I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled” (Todd, 66).