Disparate Impacts of the Fire

In continuing with the theme of class relations in Chicago during the late 19th century, it’s fascinating to look at the differential effects that the fire had on different populations throughout the city. Both spectacle and slow disasters have proved to have disparate impacts depending largely on socioeconomic status, race, gender, and a handful of other factors. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 proves to be no different in the impact that it had on particularly lower-class citizens.

Elite Crusade

As mentioned in the “Narrative” section, elite Chicagoans felt that they were in charge of the public good in the aftermath of the fire, implementing a number of policies that, again, they felt would benefit the most citizens. However, one of these policies was particularly detrimental to the lower-class Chicagoans, effectively forcing many of them out of the city. Given the sizable destruction of the fire, they felt the best way to prevent another fire of its size was to ban wooden construction in the city. Banning wooden structures meant that anyone looking to build would need to use fireproof materials that were much more expensive than wood. For obvious reasons, working-class residents and immigrants were not in favor of these construction policies. They were unable to afford the fireproof materials that were now required, such as brick, stone, marble, and limestone (Schons 2011). Thousands of citizens, along with small businesses, were forced out of the city due to their inability to afford the materials they would need to rebuild their properties or insure their properties, another requirement set in place in the aftermath of the fire. Wealthier citizens whose homes were destroyed (much fewer than the working-class) had little issue with paying extra to rebuild their property with fireproof materials and purchase fire insurance. Thus, while many working-class citizens and immigrants were forced out of the city in the months following the fire, wealthier Chicagoans had the funds to rebuild their homes and remain in the city.

Wealth Disparities

As noted in the section titled “The Great Rebuilding”, the implementation of certain policies, specifically the enforcement of stricter fire codes surrounding construction of homes and businesses, had a significant impact on lower-class Chicagoans. Additionally, at the time of the fire, cheap transportation to the outskirts of the city made middle-class dispersal easier, however, downtown Chicago was very congested, and the majority of the residents were lower-class citizens who couldn’t afford to live in the outskirts of the city.

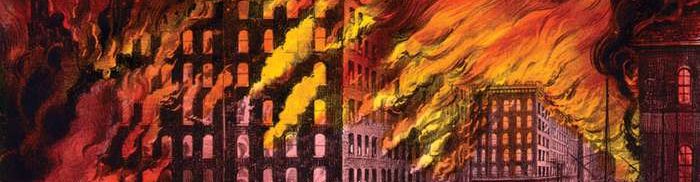

A stampede of Chicagoans running from the flames

Thus, the nature of the residential areas throughout Chicago and the nearby suburbs was largely dependent on income. The “cheap” price of transportation to outside the city was a price that was feasible for middle- to upper-class citizens who lived in the suburbs and often traveled into the city for work or entertainment (Britannica 2020). Nonetheless, the price was not necessarily “cheap” for all classes, thus, citizens who weren’t as wealthy, along with many immigrants who came to Chicago for work, could only afford to live in the substandard housing downtown. As the fire burned in early October of 1871, it spread rapidly, reaching downtown Chicago with relative ease and destroying large portions of the “slums”, where working-class citizens and immigrants were living.

Wealth disparities in Chicago at the time of the fire were the major source of the differential effects that the disaster had across populations.