The Great Depression, Great Recession, and current pandemic’s effects on the economy presented different obstacles for the American people, yet one common theme prevailed: they brought to light and intensified existing structural inefficiencies. The Great Depression and Great Recession have striking similarities in terms of cyclical booms followed by a bust while the pandemic shows us how human action can complicate a natural event.

The Great Depression (1929-1941) and the Dust Bowl (1931-1939)

After WWI, countries returned to the international gold standard and US share prices skyrocketed in a rapidly expanding economy. The Roaring Twenties brought speculation and overleveraged investments, and the Federal Reserve worried that a booming economy would increase inflation as well as enhance financial speculation. The Fed sold almost ¾ of their treasury holdings and increased the discount rate from 3.5%-5% causing the money/gold ratio, the money supply, to decline in the United States (Bernanke 9-10).

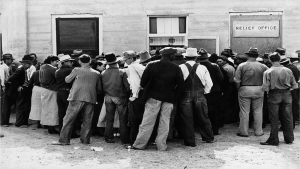

The stock market crashed on Tuesday, October 29, 1929, but the Fed exacerbated the crisis by continuing to conduct contractionary monetary policy, refusing to act as a lender of last resort, and watching mass insolvency spread. While the Fed had good intentions of preserving consumer confidence, as a 16 year-old institution in 1929, it lacked the structure, communication, and resources to understand that monetary policies and interest rates were linked to each other. Since exchange rates were fixed to the gold standard, other countries induced contractionary policies to keep interest rates parallel, causing a global crisis. The Austrian Kreditanstalt failure sparked banking panics and business failures but when they occurred, the Fed was unable to act as a lender of last resort due to the removal of clearinghouses in 1913, resulting in a choke of credit flow (Bernanke, 11). Further, as nominal income decreased, debt deflation caused mass insolvencies, amplifying fears of consumers and investors; these events all led to a continued decrease in output (Bernanke, viii and 6). These financial hardships were compounded by droughts in the Great Plains which further decreased output and increased unemployment. Aggregate demand decreased but wages were sticky so unemployment increased.

ysr< y* so usr< u*

where:

ysr = output during Great Depression & Dust Bowl

y* = potential output

usr= unemployment during Great Depression & Dust Bowl

u* = unemployment during Great Depression/Dust Bowl

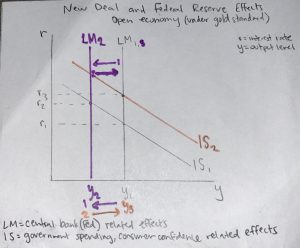

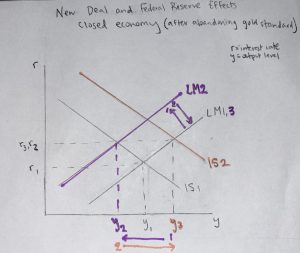

Delayed Corrective Actions by Government and Federal Reserve

In 1934, the Fed increased the nominal price of gold to expand the money supply. The institution finally realized the gold standard should be abandoned and the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 ended the use of gold as the currency in the United States (Bernanke, vii). Also, the Fed used open market check writing to buy government securities and cut discount rates to increase the flow of credit. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal included numerous banking reforms, conservation programs, and farmer protection laws to rectify an unorganized banking system, rehabilitate ruined land, and decrease unemployment. The Glass-Steagall Act controlled speculation and separated commercial and investment banks from each other, preventing banks from investing depositors’ money. The creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insured deposits which calmed consumers. While the Securities Act of 1933 added disclosure and auditing authority, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) creation was one of the most important legislative outcomes because of the supervision and investigative power it now had over the financial system. Another important law was the Banking Act of 1935 which reorganized the Federal Reserve system, uniting the branches together (“Timeline: The Dust Bowl”). The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) allowed the federal government to buy a surplus of cattle and slaughter them to create artificial scarcity to drive prices up. Other acts mentioned in “A Series of (Un)fortunate Events” include: CCC, WPA, FSRC, and DRS.

Infrastructure projects created jobs for workers and an increase in money supply led to inflation. Bank runs ended as credibility of banks increased due to deposit insurance. Under military Keynesianism, WWII military spending boosted economic growth and brought the United States closer to full employment by 1941 (“Timeline: The Dust Bowl”).

Long Term Lessons

It would be remiss to not identify and celebrate the lessons and benefits of disasters. The Great Depression raised questions of big government intervening into private life. Many believed the New Deal was an example of government overreach. However, it is important to note that it was expansionary fiscal policy through the New Deal that began to combat the effects of the Depression, not monetary policy, and ultimately the combination with WWII that brought the U.S. out of the recession. The large amount of government spending concerned some as well because of the increasing U.S. government deficit. Others argued that the government inadequately responded to the disaster because it took Congress until 1935 to declare soil erosion “a national menace” (“Timeline: The Dust Bowl”). However, even today, climate change is still not formally recognized by the current U.S. administration, and so there are lessons from the Dust Bowl that should be taken more seriously.

The Great Recession (2007-2009)

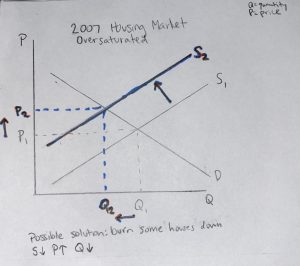

80 years later, the financial system had weakened again; there were too many complexities in the system and not enough transparency between banks and the government (Geithner, 3). Similar to the Roaring 20s, in the decade prior to the Great Recession, everyone, including credit raters and traders, was making money off of packaging assets in nuanced ways, and the average American was living their dream: buying a big house. Here, identifying blame may seem more clear since the Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 did not contain an unavoidable drought. While this may be true, there were many groups involved that make it difficult to point a villain out. Few people realized nor cared about the consequences because no one thought that housing prices would fall. The Gramm-Leach Bliley Act repealed the Glass Steagall Act in 1999, allowing commercial banks and investment banks to combine again, enabling them to invest depositors’ money in unregulated derivatives. The subprime mortgage market targeted less creditworthy borrowers at artificially low rates. Moreover, insurers such as AIG were betting on the U.S. housing market, inflating its bubble (Geithner, 4-5). Frannie Mae and Freddie Mac, housing giants that backed mortgages, were unable to meet payments when the housing market bubble burst in late 2007, so bank runs ensued (Geithner, 4).

Trial and Error Actions by Government and Federal Reserve

Ben Bernanke and Hank Paulson’s staff thought the bust would be contained to the housing sector but failed to understand how complex the system was. When the housing crisis spread to the financial sector, the Federal Reserve assisted J.P. Morgan’s purchase of a sinking Bear Stearns by buying the toxic assets off their balance sheet, but shortly thereafter they allowed Lehman Brothers to fail due to moral hazard fundamentalists’ push for less government intervention in remedying financial crises. Investors and consumers, confused by the switch, lost confidence in the system and reacted in fear that the government would continue to allow banks to fail (Geithner, 6). Since the market was oversaturated with homes, at one point, there was even talk about burning houses down to bring the prices up, similar to killing cattle during the Great Depression.

Eventual Coordinated Actions

The FDIC, established in 1933 as part of the Banking Act of 1933, guaranteed deposits again calming consumers (Geithner, 226). In an effort to increase the money supply, the Fed bought government bonds and mortgage-backed securities off the open market through multiple rounds of quantitative easing and announced interest rates near zero. However, the pivotal action was the introduction and use of Stress Tests (Geithner, 238). After searching major financial firms’ books, regulators calculate how much additional capital they would need to survive a catastrophic crash; firms then required to raise enough capital to fill the gap but if not able to raise enough from private investors, the government would forcibly inject the missing capital but remain a minority and silent stakeholder. The cash for capital injections came from the TARP stimulus package worth $700 billion (Geithner, 224).

Long Term Lessons

Ben Bernanke at the helm was instrumental to the understanding that swift but cautious coordinated action between the Fed and federal government was paramount, using lessons learned from the Great Depression. Tim Geithner’s leadership and creativity led to the Stress Test, and the financial system ended up repaying the TARP assistance back to taxpayers which turned a profit, surprisingly. The alternative was to directly purchase toxic assets which the TARP money would not have been able to fully remedy due to the excessive amount of collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and credit default swaps (CDS) in the subprime mortgage market (Geithner, 230). Also, banking regulations became more strict: the derivative market now had margin requirements as well as stronger capital and liquidity requirements, the shadow banking system was cut in half, and there was a push for less dependence on runnable short-term funding. The Consumer Spending Protection Bureau emerged as well. For the next decade, the financial system would remain healthy and strong due to these reforms.

COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on U.S. Economy

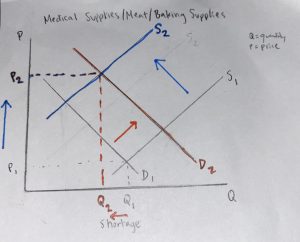

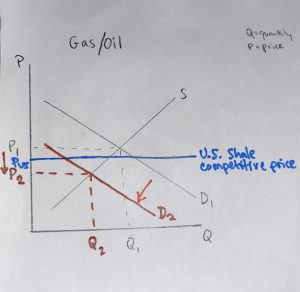

With the virus forcing closures of almost every industry in March 2020, the supply of goods such as meat and baking supplies decreased. This supply cut and an increased demand for home cooking and baking caused price increases. At the same time, necessary medical supply shortages incentivized companies to think outside the box in terms of production. Online giants such as Amazon and Target profited off of the pandemic and have seen incredible revenue streams this year. With online purchases dominating as the main form of consumption, the Federal Reserve announced a coin shortage. Furthermore, the oil feud between OPEC countries and a decreased demand in gas due to cancelled flights and work-from-home policies pushed oil prices down. The U.S. shale industry could not compete with these artificially low prices and has suffered along with the rest of the world, especially those who have lost loved ones. However, despite these closures greatly affecting the economy, Americans refuse to quarantine fully and correctly which exacerbates the deterioration of the health of people and the economy in the long run.

Unprecedented and Swift Government Actions

Congress passed the two largest stimulus packages in American history during the pandemic. The CARES Act provided direct cash payments to eligible American households, allotted cash to businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and increased benefits to the unemployed. It also sent targeted aid to the airline industry which suffered major losses last spring. The second package, a $900 billion pandemic relief bill, extended some of the relief measures from the CARES Act as well as carved some support out for the traditional entertainment industry, which is in danger of extinction as home entertainment alternatives become more popular (Lobosco & Luhby).

When the Fed unprecedentedly announced low interest rates over the weekend in March and declared that those rates would remain near zero for several years, they hoped to reassure investors and consumers that the government would not let another recession occur. While they were correct in reassuring the American public, it was the reforms that came out of the Great Depression and Great Recession that kept financial institutions from worrying about runs on banks. However, when interest rates and the yield on Treasury bonds decreased, investors flocked to the stock market, a more attractive and lucrative option to invest their money. Along with the stock market bounce-back, households took advantage of low rates and increased borrowing during this time. The Federal Reserve also expanded quantitative easing measures seen in the 2007-2009 crisis to purchase corporate bonds (ETFs) as well as the existing practice of buying government bonds. In addition, they set up the Main Street Lending Facility where companies that are too large to qualify for PPP grant money can apply for loans; these loans have more lenient terms and the Fed takes on 95% of the risk, backed by the U.S. Treasury (“Main Street Lending Facility”).

Anticipated Consequences

The bottom line is that the Fed is acting as the lender of last resort. Even though these actions lead some people to believe that it is only creating an inflated stock market that is over-speculative while further increasing the already large government deficit, instilling confidence in the system is key during a financial crisis. Unemployment was at an all-time high in March and April but has begun to decrease as phased reopenings occurred over the summer and fall. It is important to note that the government’s efforts are short-term bandages for an economy suffering from closures in all sectors and will remain that way until the virus no longer spreads at the rate it does now; the long term solution is to vaccinate as many people as possible and remain at home until then.