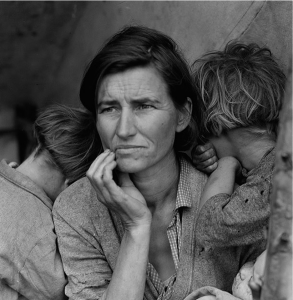

Photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein have captured the despair and hopelessness people felt during the Dust Bowl, and while they illustrated the physiological and psychological impact of the Dust Bowl, people had little understanding of the scientific impact of physical and mental toll on American households at this time. Furthermore, understanding the context of the Dust Bowl highlights that while consumer and investor confidence decreased in cities, the confidence and self-reliance of farmers shifted (PBS, 29:10).

Physical Health

Physically, the Dust Bowl inflicted pain in the lungs. Victims suffered from dust pneumonia in the lungs, “a respiratory illness” that fills the alveoli with dust (Williford). People were scared of breathing because the air itself could kill them (PBS, 14:45). Dorothy Kleffman, who was a child in Texas County, Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl, remembers that she “couldn’t see [her] hand in front [of her] face” (PBS, 23:10). When the dust storms blew, parents put “tea towels and flower sacks” over their children’s faces to protect them from the dust. To children, the severity of these storms felt the same if they had taken a handful of dirt and stuffed it in their mouth, and both children and their parents had to wash their mouth every time they arrived home because of the amount of dirt on their face from walking outside (PBS, 24:18).

Another medical consequence of the Dust Bowl was the electrical current in the air. Clarence Beck from Cimarron County, Oklahoma remembers “electricity jumping out six inches” and the car having a powerful charge. Because of the strong kinetic energy in the air, anyone who drove a car had to bring a chain and drag it behind the car to ground out the electrical current. If not, the radio would go out. Others remember their hair becoming wiry.

The physical fear of breathing in dust and getting electrocuted by the static electricity in the air altered people’s mental awareness of their surroundings as well.

Mental Health

A study included in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health explains the reasons behind the emotional toll on rural farmers’ mental health due to roles they played in society, broadly and at home.

Farmers are optimistic gamblers so when they become discouraged and give up, the Dust Bowl situation intensity becomes clear (PBS, 27:18). This phenomenon was exacerbated by societal pressures that men felt in the early 20th century to put food on their family’s table. Holly Vins, a faculty member at Emory University’s Department of Environmental Health, and her co-researchers found that “masculine hegemony dictates that men be emotionally tough, stoic in the face of adversity, and the breadwinners of the family” (Vins et al., 10). The “rural stoicism” and “culture of self-reliance” combined with male feelings of pride motivated farmers to reap plentiful harvests. However, when “drought directly impacts the employment and economic success of agricultural communities,” rural male farmers, who were normally self-reliant, were unable to provide for their families and felt helpless (Vins et al., 10) (PBS, 4:44).

The same goes for women, particularly mothers. Vins and her colleagues found that women experience “heightened vulnerability due to their roles as caregivers and household managers” (Vins et al., 10). In the PBS special event with Ken Burns, even the “most vigilant mothers could not keep dirt out of houses” (PBS, 4:46). The daily “stresses associated with those responsibilities [of caregiving and house-managing]” compounded with their inability to meet their family’s needs due to the amount of dust and dirt infecting their children’s lungs emotionally wrecked them (Vins et al., 10).

Seasonal Depression

The American Psychiatric Association published a section on Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), commonly known as seasonal depression, and it is clear that people who endured life during the Dust Bowl suffered from this disorder without realizing it at the time (Torres). It was not that they were ignorant to it, but that mental health was not commonly discussed in the early 20th century. In fact, in rural areas, there was an even greater stigma surrounding mental health discussions (Vins et al. 10). Dr. Felix Torres, the physician who reviewed the section writes:

SAD has been linked to a biochemical imbalance in the brain prompted by shorter daylight hours and less sunlight in winter. As seasons change, people experience a shift in their biological internal clock or circadian rhythm that can cause them to be out of step with their daily schedule. SAD is more common in people living far from the equator where there are fewer daylight hours in the winter.

While I was unable to find research connecting the Dust Bowl to SAD, the Dust Bowl case certainly qualifies for inducing seasonal depression in people who lived in the Great Plains due to the eight years of severely decreased sunlight. Shirley Forester McKenzie from Texas County, Oklahoma recalls the dark, black, and scary sky (PBS, 20:46). The dust clouds would engulf and “erase the sun midday” (PBS, 5:30). Pauline Durrett Robertson from Potter County, Texas reminisces about the wind and dirt that had different colors depending on where they came from; the dust would be sandier at lower elevations and could take paint off of cars like sandpaper (PBS, 21:05). Even more terrifying were the black blizzards, fine particles that rose 8000 feet with gale forces ranging 40-60 mph. Stretching 100 miles wide and one mile high, these storms looked like a mountain range, but they moved, further generating uncertainty and fear (PBS, 22:38).

The best example that connects the Dust Bowl to seasonal affective disorder are the events that took place on Palm Sunday in April 1935, later named Black Sunday. That morning, people woke up, could see the sky outside, and opened their windows for rare fresh air. They thought they had survived the four years of drought and expected rainfall that day. Since it was Palm Sunday and a nice day, families arranged picnics with neighbors and extended family. However, in the middle of the day, they realized that what looked like rain clouds were actually dust clouds. The dark storm caught people outside of their homes and trapped them in cars and under picnic blankets. When families were able to return home, they had to shovel the dust from their doorsteps and inside their homes because it had been the worst storm they had seen yet, and it had caught them when they let their guard down. When the weather was nice, families’ moods were bright and lighthearted; however, when the sky turned dark against them, they became grim and unhappy.

Artists such as Woody Guthrie sing about the Dust Bowl Blues, but there is little scientific knowledge or research about mental health in the 1930s and the PTSD effects that children of the Dust Bowl still feel decades later (Williford).