Infantile Desire in I Kill Myself

Julian Kawalec’s short story, “I Kill Myself,” written in 1962, is a prime example of New Wave psychological SF. Kawalec’s narrator, an unnamed lab technician working to develop and mass produce the Zeta Bomb— the ultimate weapon of destruction— decides to steal and destroy it instead, hoping to keep the world safe. The narrator grows to covet the Bomb, however, and keeps it for himself. He fantasizes about the Bomb’s power, ultimately proclaiming himself “God.” Central to the story is the narrator’s psychological “u-turn:” his original desire to destroy Zeta transforms into a desire for Zeta. The significance of the narrator’s u-turn can be interpreted as an example of humans’ desire for power and expanded into a metaphor for humans’ inability to control their desire for pleasure-inducing technology, an interpretation crucial to communicate in contemporary times.

The narrator’s psychological u-turn, however, contains more than a conscious reversal of his desires. Rather, as a psychoanalytic interpretation of the text reveals, his u-turn is a consequence of his id (his unconscious wishes), which seizes control of him once he has the Bomb. The narrator’s ego is rendered powerless and its capacity for reality testing reduced to nothing. The narrator’s u-turn reveals that humans’ submission to technology is not merely the bending of our conscious will. On the contrary, it is a result of an internal force often unstoppable when paired with pleasure-inducing technology. This revelation is infinitely more useful to society, for it informs us that in our attempts to stall pleasure-tech, we are up against a formidable opponent.

One’s repressed desires are, under normal circumstances, repressed or transformed by the ego into something consciously palatable. The narrator’s ego in this story, however, cannot prevent his infantile desires, namely those Oedipal and narcissistic in nature, from resurfacing. Faced with this stress, the narrator resorts to the defenses of rationalization and suppression.

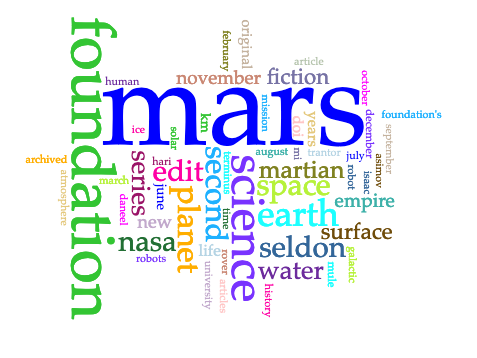

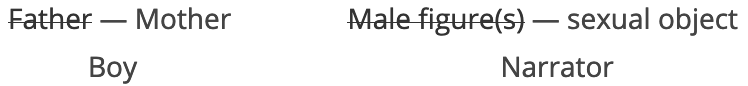

Three oedipal wishes manifest upon the narrator’s possession of Zeta. His wishes parallel the Oedipus Complex in that they involve the narrator’s removal of some sexual object from some male figure(s) while simultaneously causing them pain. This constitutes a triad similar to the Oedipal triad:

In the narrator’s first oedipal wish, he considers revenge against his lab workers, and more importantly, his boss. He imagines “command[ing] them to march to a hollow between hills and leav[ing] them there, and starv[ing] them” (Kawalec 266). This desire for cruel revenge parallels the Boy’s hate towards his Father. Zeta’s status as a sexual object, however, is not immediate; in fact, its sexual connotations grow once it is stolen. Prior to being stolen, Zeta is first described as a “steel child… cold and slippery… monstrous” (Kawalec 260-2). Once stolen, Zeta “reminds [the narrator]… more insistently of its presence,” growing “warmer… [and not] so ugly” as before (Kawalec 264), until it is “warm,” with “smooth metal” (Kawalec 265). Once the narrator decides not to destroy it, he proceeds to “touch Zeta… stroke it.” Zeta is “beautiful… smooth… pleasant”. He “press[es] Zeta to [his] heart… kiss[es] it” (Kawalec 267). Zeta transforms from cold and inanimate to warm and fetishized. The narrator’s desire to kill his senior lab workers and covet Zeta parallel the Boy’s desire to kill his Father and possess his Mother. We can map the Oedipal triad:

Continue reading →