What happens to a symbol when it is forcefully detached from its original meaning? Does it float off into semiotic oblivion, subordinated to whatever new context it has been placed in? Does it retain any of its previous separate power?

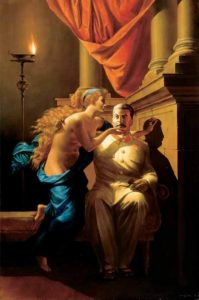

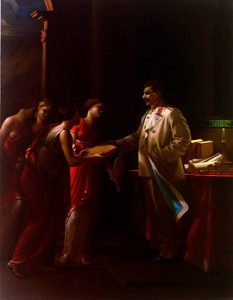

Komar and Melamid’s work is interesting on a few levels. The socio-political satire is, of course, biting and inventive: The Origin of Socialist Realism depicts Stalin, statuesque and incongruous in a poorly-lit semi-classical setting, visited by the Muse. Stalin and the Muses shows Stalin accepting a book from the Muses, radiating a dark light, in front of his desk (yet is it ‘his’? Once more, he is a statue). In Lenin Lived, Lives, and Will Live, the revolutionary may as well be some slain Danaan, weeped for by a shrouded women. These statements are clever, but do they move?

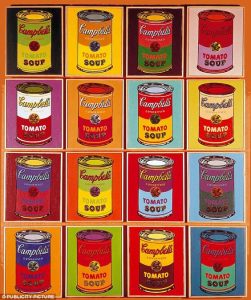

SOTS Art provides an interesting counterpart to Western pop art: the ubiquitous images of consumerism replaced with the ubiquitous images of totalitarianism. The Campbell’s Soup Can, however, is really only interesting because it has been placed into the new context (Warhol’s pop art). There it is!, we say- the things we buy, speaking back to us in technicolor.

A dictator speaks back a little louder. But does he always say the same thing? When Stalin is collaged into one of Komar and Melamid’s works, is he still ‘Stalin’? After we appreciate the parody, the ‘artistic statement,’ the polemic on socialist realism, does his image still conjure terror, awe, love, confusion? (I speak here about a Russian audience-the image of the dictator, any dictator, conjures up for most American students only a sort of amused, negative-reverent ‘oh yes, him.’ How many of us have seen this blog? http://kimjongillookingatthings.tumblr.com/)

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes wrote that

“When we define the Photograph as a motionless image, this does not mean only that the figures it represents do not move; it means that they do not (i)emerge(i), do not (i)leave(i): they are anesthetized and fastened down, like butterflies.”

These images of Stalin (and Lenin) are not photographs, but they are ‘photographic’- they pin down the ‘man’ (made larger than life) in time and space. Work like Komar and Melamid’s unfastens the image from propagandic contexts, but, to me, it seems that Stalin doesn’t really stop being Stalin, that is to say, the parody might be, inadvertently, a parody of itself too. The Archetypal Dictator is made ridiculous, yet he is still present, a ‘Big Other’ poked at but looking back mutely, fixedly. In her work Second-Hand Time, Svetlana Alekseevich interviews a young man who tells an archetypal story about Stalin: at his dacha, a portrait of him hung. Stalin would point to the picture, addressing his children: “That is Stalin.” Then to himself – “This is not Stalin.” We must ask ourselves: are the re-contextualized figures in Komar and Melamid’s “Nostalgic Socialist Realism” still ‘themselves’?