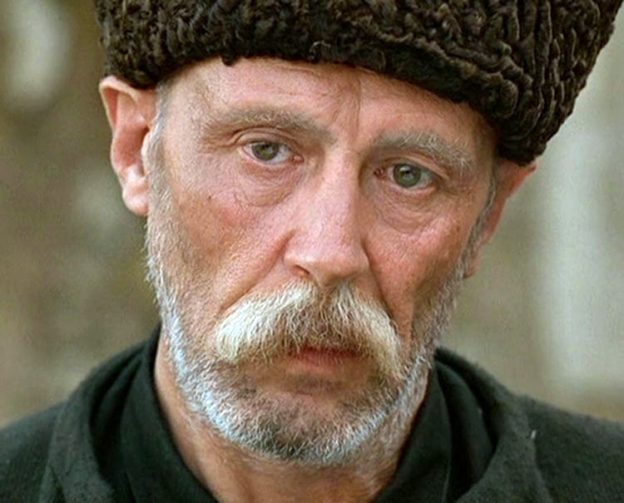

In Maxim Maximych’s retelling of the former lietenant’s story, his explanations of the tense yet intimate relationship between the Chechen people and the travelers/foreigners is mentioned. Specifically, I noticed the relationship between the portrayal of Chechen people in light of Maximych’s retelling of his story of the former lieutenant’s adventures and his interactions with Chechen characters. In the beginning of this text, there was definitely a distant, cold connection highlighted by certain comments about the Chechen people. For instance, the Chechen wedding customs were retold in the perspective of an observer rather than in the perspective of a companion. This distinction shows that the Chechen people, as well as other indigenous groups, are categorized as “other.” This “otherness” is what I found most intriguing about this text. I addition to the cold remarks about the character of Chechen people, they are referred to by different names such as Circassians and Asiatics. This further removes them from familiarity with both the Maximych and the lieutenant.

However, this cold view of the Chechen people is melted away with the introduction of Bela. Bela serves as a breakaway from the “other people” perspective. In light of her beauty, she is adored by Kazbich and other foreigners, most notably Pechorin. Pechorin wins her favor by giving her expensive gifts and respecting her wishes, as well as caring for her. Her death by the hands of Kazbich highlights the emotional attachment that Maximych, the lieutenant, and Pechorin feel after her death. In this way, the observer outlook of the Chechen people is washed away to be replaced by a more emotional and humanistic depiction.