Kar Wai Wang’s 2000 film In the Mood for Love vividly captures not only a romance between two neighbors who find their spouses in an adulterous relationship, but also the sartorial choices that show Hong Kong in the 1960s caught between East and West.

To make reference to the broader historical framework, Hong Kong developed separately from the rest of China owing to its special relationship with the British who acquired a 99 year lease on the island. While China was in the midsts of communism and famine, Hong Kong stood as a beacon of capitalism and entrepreneurship in the East. Many Western companies set up offices in Hong Kong to have a stake in Asia, but one mediated by a familiar power: the British. The introduction of Western businesses and Western business techniques gave rise to domestic companies owned by citizens of Hong Kong who have made the city a global economic powerhouse with a commanding role in the finance industry.

Despite this Western flair, Hong Kong never completed shed its China roots and this is evident in the 2000 film In the Mood for Love as evidenced in the above scene where Mrs. Chan is saying goodbye to her boss who is leaving to have dinner with his wife. The boss is depicted in a Western style suit with distinctly modern influences. His suit is excellently tailored, perfectly terminating at his shoulders. The sleeves are precisely long enough to reveal the edge of his light blue shirt with French cuffs and the subtle, yet sophisticated cufflinks. His tie features a modern paisley pattern that terminates exactly above his belt buckle that widens ever so slightly as it moves from top to bottom.

In contrast, one of the few shots where Mr. Chow is fully visible reveals a distinctly different character. His tie, unlike Mrs. Chan’s boss visibly clashes with his shirt. Furthermore, it is far wider at the bottom than at the top. Such is a fashion style commonly associated with a tacky used car salesman. Finally, he is tied it inappropriately such that it falls when standing where his zipper begins rather than where ending above his belt buckle as shown by Mrs. Chan’s boss.

What this suggests is an incomplete adoption of Western fashion trends that unfolds along class lines. Her boss, the owner of a successful import/export business whose business spans across the globe likely has both the exposure to Westerners through business meetings and the financial resources to appropriately wear Western clothing. Mr. Chow, a low level functionary at a print company, likely has little exposure to such people and his needing to rent a room speaks to lacking much disposable income. What matters for Mr. Chow, who is an archetypal common white collar male in 1960s Hong Kong, is the appearance of being Western rather than complete adoption of their sartorial forms.

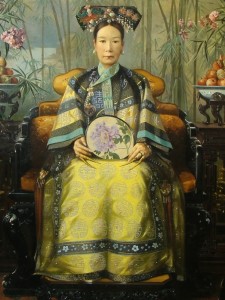

Both Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan’s boss’s clothing choices stand in stark contrast to hers. She is seen wearing a high collared Qipao that evokes images of Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s. Unlike them, however, her clothing features very rich and vibrant colors of purple and yellow in complex flowing patterns. Such complex patterning is made possible by dyes and techniques of modern clothing manufacturing. Furthermore, it is sleeveless. The lack of sleeves, vibrant colors speak to a marked departure from early Qipao styles dominated by floral images, the color red and short sleeves. She is also seen later carrying a western style not unlike those you would see sold today in Western department stores and boutiques.

The juxtaposition of these three characters reveal is the complex identity of Hong Kong during the 1960s as it straddled East and West culturally, independent of China. The highest members of society, symbolized by Mrs. Chan’s boss, had the cultural knowledge and financial resources to perfectly mimic Western fashion styles. When juxtaposed with the lowly Mr. Chow who poorly pulls off a Western look, it is clear that the aspiration of Chinese men as they became more successful was to look more perfectly Western in their clothing choices. Mrs. Chan stands in contrast throughout the filming by always wearing Qipaos rather than Western dresses. Although they are clearly influenced by Western designs by abandoning the design elements of the 1920s and 1930s, women nevertheless attempted to preserve the traditional clothing style. Thus, it can be seen that modernity as imagined by women in the 1960s consisted of subsuming Western materials, patterns and manufacturing techniques within the traditional qipao style.