Although Western powers were able to secure enormous concessions from the Qing emperor during the latter part of the 19th century, there was no doubt among the Chinese people in the preceding years that absolute authority rested with the imperial state. For much of the Qing dynasty, power rested in the hands of an emperor, not an empress. His clothing, the dragon robe, was replete with cultural symbols that signified his absolute sovereignty over the state. However, power shifted from men to women during the reign of the Tongzhi and Guangxu emperors because both of them ascended while still children. Real authority rested with their mother and aunt respectively: Empress Dowager Cixi. This paper will compare the robes of earlier emperors and empresses with the qipao worn by Cixi to reveal how cultural symbols reserved for the male emperors came to be incorporated in Cixi’s robes.

Emperor’s Dragon Robe

Artist/maker unknown, Daoguang Period (1821-1850), c. 1840, reproduced from ArtStor.

This first image is a picture of the emperor’s dragon robes. When comparing them with the empress’s dragon robes below, one can immediately note the color difference. Culturally, yellow is associated with the earth and symbolizes the center of everything. It is fitting, therefore, that the male emperor of China be clad predominately in yellow. His dragon in the center of his chest is one of nine that harken back to the Huangdi Emperor, also known as the Yellow Emperor, who brought order to China through literacy. While the individual characters may say longevity or judgment, together they refer to the imperial literary tradition of enlightened rule inherited from Huangdi. The prominent number of clouds, as well as the sun, stars and moon symbolize his connection to the heavens as the Son of Heaven, tianzi.

Women’s dragon robe.

Artist/maker unknown, Qianlong Period (1736-1795), c. 1740, reproduced from ArtStor.

In contrast to the emperor’s dragon robe seen above, the female dragon robe makes limited use of imperial symbology. Most prominent is the limited use of the color yellow, which underscores that it was a color out of reach of even the most powerful woman in China. Furthermore, her dragons are brown rather than yellow. This underscores that men, not women, were the only ones who could claim affiliation with the great Huangdi. She has far fewer clouds on her robes than a male emperor, which signifies her distance from the heavens as only men can hold the Mandate of Heaven. Lastly, her robes lack the writing seen on the emperor’s robes. Recalling that this writing had three connotations – judgment, longevity and enlightenment – their total absence suggests imperial disregard for those three virtues even for an empress.

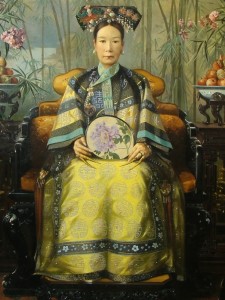

Oil painting of Empress Dowager Cixi by Hubert Vos, 1906.

As this painting of Empress Dowager Cixi by Hubert Vos in 1906 demonstrates, Cixi’s robe is a dramatic departure from those of preceding centuries, which symbolizes her transcending traditional gender norms. It is important to note that Hubert Vos was tasked with making official portraits of Cixi, one of which still hangs in the palace. Therefore, his paintings are intended to be faithful portrayals of her likeness. It is also worth emphasizing why it is more appropriate to refer to her garment as a qipao rather than a dragon robe: there is not a dragon on it. Furthermore, it lacks the many of the traditional symbols – clouds, stars, mountains, sacrificial cups, among others – that characterized centuries of imperial robes. Wearing a qipao in this style rather than the dragon robes appropriate to an empress during the Qianlong era symbolized her autonomy over her clothing and China by extension.

Nevertheless, Cixi did clearly appropriate elements of the male dragon robe for her qipao to underscore her authority. The most striking comparison with the dragon robe worn by most empresses is the enormous use of yellow in her qipao. Her symbolically appropriating the color of earth, over which a man normally reigned, illustrates her supremacy over the state. Furthermore, her robe prominently features characters symbolizing longevity. As illustrated in the previous dragon robes, writing – which connoted judgment, longevity and enlightenment – was reserved exclusively for men. By incorporating them on her robe, she stakes claim on those three connotations as though to say that her reign is one characterized by enlightenment, justice and stability. However, the sheer number of the symbols of longevity on every portion of her robe symbolizes her desire to reign as long as possible to ensure a stable, prosperous China.

Her renewing the traditional qipao rather than the dragon robe might also have historical significance when one considers the events during her reign. During this time, the dynasty was forced to make more and more concessions to foreign powers at gunpoint. They introduced opium to the population, which crippled their ability to resist. These foreigners secured extraterritoriality, allowing them to evade imperial justice for their crimes. In these times of weakness for the Chinese state, wearing a cheongsam might have been Cixi’s longing for the era where Manchu women were the foreigners who were conquering a weak Chinese empire rather than being the ones conquered by foreigners.

nice work, the claim is well supported.