Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) was a Northern Italian artist who spent the majority of his time in Rome. At the age of 20, Piranesi worked among famous printmakers in the city, and he established his unique style of etchings. His technique allowed for a deep contrast between light and dark in his prints—reconstructing a powerful image of the scene he depicted. Piranesi specialized in classical antiquities and Renaissance and Baroque structures, visiting these sites firsthand to do his etchings.

The Bowdoin College Museum of Art features a vast collection of his etchings, and the ones of interest to this project include his works of the Roman Colosseum ruins and the Amphitheater of Verona.

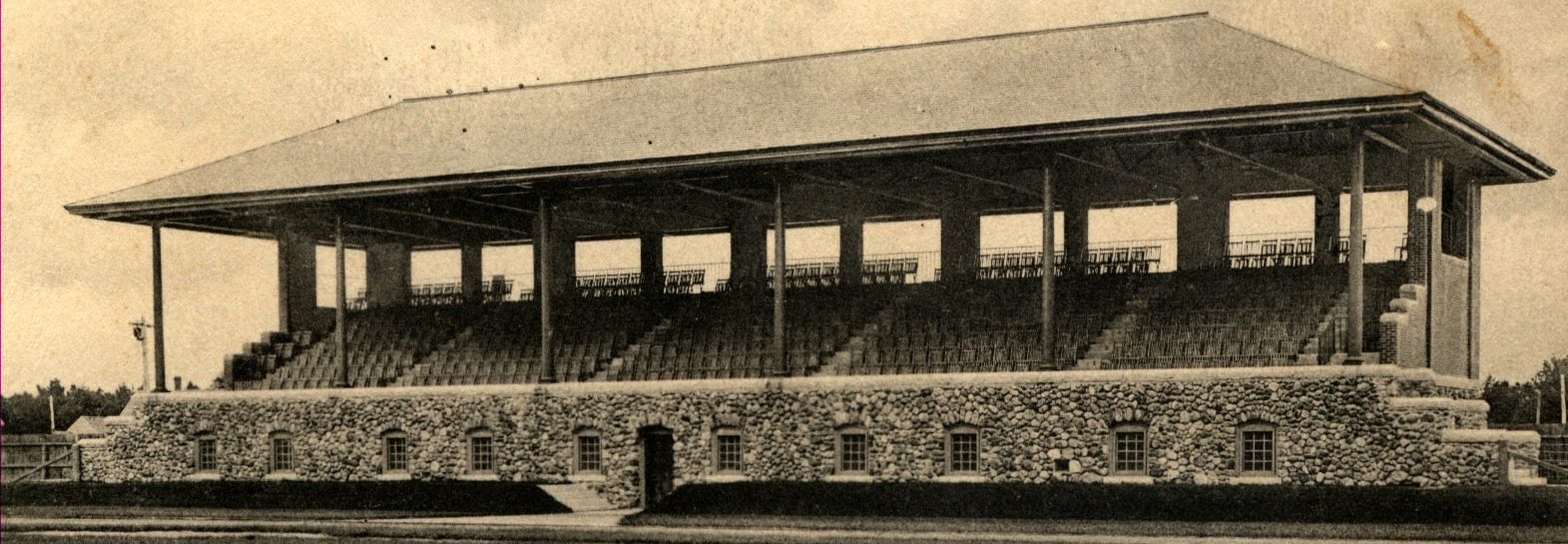

The exterior of the Coliseum, etching and drypoint on paper, 1750-1759. Courtesy Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

Completed in 82 A.D. as a gift to the people of Rome, an emperor of the Flavian dynasty, Vespasian, commissioned the construction of the amphitheater so the citizens could enjoy gladiator events and other forms of entertainment. The Colosseum, unlike many of the other stadiums from its time, was not built into the ground; it was freestanding, making it an imposing structure in the city of Rome. The building itself has distinctive arched entrances and columns of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian order. The Colosseum could house 50,000 spectators, and people were seated based on ranking. To protect spectators from the sun, awnings could unfurl so as to provide shade.

Interior of Colosseum, 1757. Courtesy Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

The Colosseum was used for gladiator and other fights and events for nearly four centuries, but eventually, public interest dissipated and it was abandoned. The building fell into disrepair and ruin after that—in fact, it was even used as a quarry for some other projects in the city. By the 18th century, Popes began to take interest in restoring the structure, but it was not until the late 20th century that serious efforts were made. By then, approximately two-thirds of the original Colosseum had been destroyed from weather and vandalism over the years.

Piranesi’s etchings of the Colosseum offer unique documentation of the structure’s history. He simultaneously captured both the beauty of the structure and its state of ruin. The views of the interior, particularly, reveal how much of the original structure was lost over the centuries of its abandonment. Interestingly, the timing of Piranesi’s prints falls just before the Colosseum became a major tourist destination. His work depicts the building at a time before any major restoration efforts, meaning it memorializes it at a little-seen state.

View of the Colosseum, Interior, 1776. Courtesy Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

The second etching of the interior offers an aerial view, demonstrating Piranesi’s powerful use of perspective. This work, done in 1776, shows the crucifix and stations of the cross Pope Benedict XIV installed in 1743. He captures the Pope’s intention to revive the space between the later period of major restoration and the period in which it was completely abandoned and in ruin.

In addition to Piranesi’s etchings of the Roman Colesseum, the Bowdoin Art Museum also has one of his etchings of the Amphitheater of Verona. Constructed in the first century, this arena held a similar purpose to the Colesseum. Its size is not as grand as the Colesseum, holding approximately 20,000 spectators. However, its condition today is much better off, and it still hosts events.

The Amphitheater holds a vast history of hosting events. When it was first constructed, it held processions, dance and music performances, and blood sports. By the 16th and 17th centuries, it held tournaments and games. Even today, audiences flock from all over the world to watch operas and performances from more contemporary artists such as Adele and Pearl Jam.

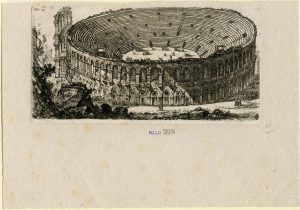

Amphitheater of Verona, 1743 etching. Courtesy Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

Piranesi, similarly to his work with the Colesseum, used a birds-eye-view perspective to capture the grandiose qualities of the arena. His work emphasizes the functionality of the space; by including figures inside and around the structure, he highlights its centrality to Veronese culture. The arena today is seen to be one of the best-preserved monuments and serves as a symbol for ancient nobility.

Piranesi’s minute attention to detail in his etchings of the Colosseum and Amphitheater of Verona demonstrate his intention to commemorate the structures. His etchings provide a depiction of Roman buildings that celebrates architectural achievements. It is as if his own fine work is a tribute to the past work of the Roman Empire. In addition, Piranesi shows the centuries-old value of supporting sporting events and spectating. The pure size of these arenas proves that Romans placed entertainment by sport at the center of their culture—and literally at the center of their cities. Piranesi captures an era in the history of these structures that accentuates their enduring qualities—displaying both their slow decay and their persisting functionality.

Cartwright, Mark. “Roman Verona.” World History Encyclopedia, World History Encyclopedia, 12 May 2021, www.worldhistory.org/Verona/. “Collections.” Collections (Bowdoin College Museum of Art), artmuseum.bowdoin.edu/. “Colosseum.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/topic/Colosseum. “Giovanni Battista Piranesi.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/biography/Giovanni-Battista-Piranesi. History.com Editors. “Colosseum.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/colosseum. Metmuseum.org, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/360270. Wang, Ione. “A Brief History of the Verona Arena.” Culture Trip, The Culture Trip, 3 Aug. 2017, theculturetrip.com/europe/italy/articles/a-brief-history-of-the-verona-arena/.