The major aspects of memorialization presented in this project—renovation, documentation, preservation, and restoration—highlight the distinctive yet subtle ways in which human culture celebrates athletics. Often, when people think of memorials or commemorative sites they imagine a plaque or piece of writing that briefly outlines the history of a certain place. Athletic facility memorialization exists in a less traditional way. The buildings stand for themselves, and remnants of their past history hide in the layers of their structure.

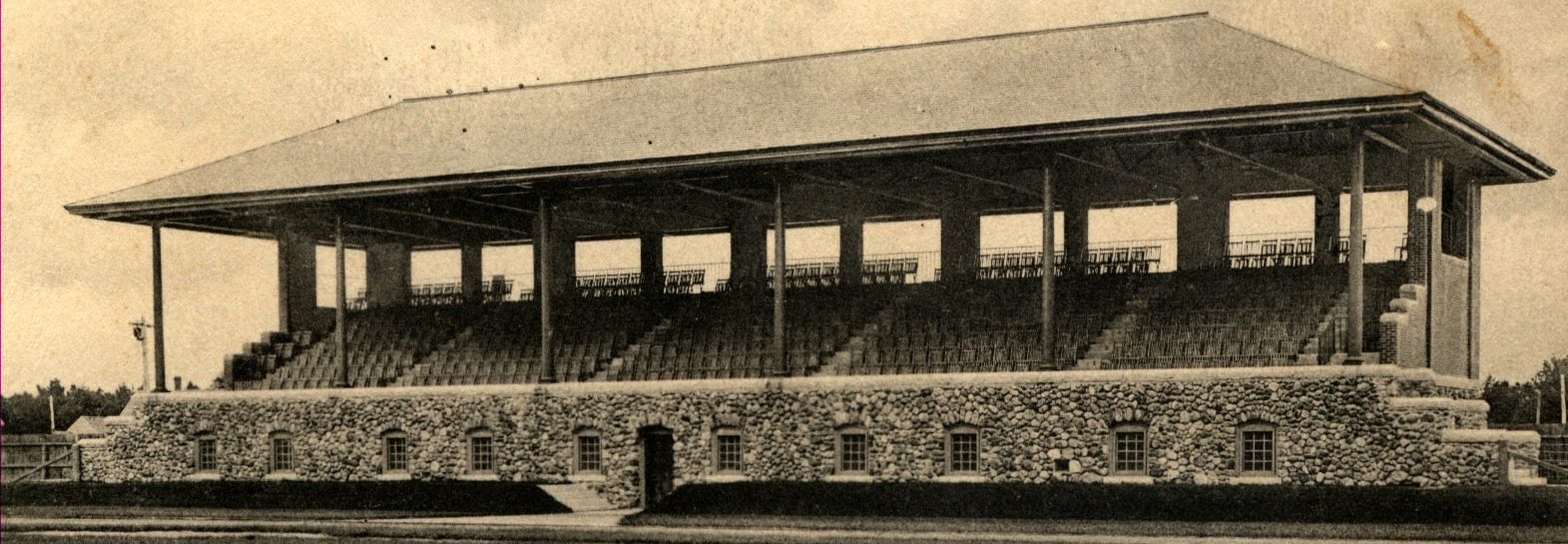

The renovations of Bowdoin College’s athletic facilities introduce perhaps the most subtle forms of remembrance. As the College grew and the need for athletic sites mounted and changed, the school creatively adapted to the construction process. Instead of merely tearing down and rebuilding facilities—which has become common at most schools—Bowdoin found new purposes for the past buildings. The Sargent Gym became a heating plant, the Hyde Athletic Cage was renovated to become Smith Student Union, and Curtis Pool was turned into a recital hall. In a similar vein, Hubbard Grandstand is on the registry of historic places, and the College has prioritized maintaining that space despite the growing student body. None of these locations have any sort of plaque or official mark that serves as a memorial to the building’s past use. Instead, the act of repurposing them in and of itself serves as the memorial. The building’s original shape serves as a reminder of their past, and other remnants are also visible, such as the painted markings of the track distances in Smith Union. Bowdoin’s memorialization is subtle, and perhaps that makes the new spaces more genuine.

Piranesi’s prints, too, act as a subtle form of remembrance. While it is difficult to know the artist’s intention for documenting them, it is likely that he saw them as a great model to test his skills. His etchings are much more than just an image of a scene—they serve as a historical record for the Colosseum and Amphitheater during the era in which he depicted them. His work also further emphasizes our culture’s celebration of athletics as a community event. The grandiose nature of the sites places athletics as the focal point of city life. By having these sites documented in a different era, we have access to a more vast time period to place them in our memory.

Similar to the Roman Colosseum, the ancient site of Olympia is one of the most visited ruins in the world. Human fascination with ruins introduces an interesting form of memorialization. By preserving a site in its state of ruin, it captures a place after its prime. In some ways, ruins are more fascinating than ancient sites that are in use, as their state of decay reminds us of the vast amount of time that exists between their past and our present. The rudimentary characteristics of Olympia remind us of how drastically athletic facilities have evolved over time.

In a similar vein to the Amphitheater of Verona, the Panathenaic Stadium is one of the oldest sites that are still in use. These places hold a certain cultural power, as attending an event in them connects a spectator to centuries and millennia of athletic history. By restoring these sites to ensure their functionality, we commemorate their past by welcoming it into our present. This project demonstrates that memorials do not always take a traditional form. Commemoration can exist through the repurposing, documentation, or preservation of a space. In some ways, these forms of remembering are more powerful because we can experience them and their functionality as opposed to merely reading or hearing about them. The physicality and grandiose nature of athletic facilities provide a powerful form of commemoration. These places feel as much a part of our present as they do of our past.