Introduction

The evolving history of Bowdoin’s architecture and buildings in regards to athletics introduces a unique aspect of memorialization and memory. Over the past 150 years, as the student body has grown and societal attention to athletics has mounted, the College has uniquely adapted—creatively building, renovating, and remodeling facilities on campus to meet the needs of the students and athletic department.

Old Sargent Gym and Heating Plant

While athletics are clearly a prominent aspect of the American college experience today, Patricia Anderson describes in her book, The Architecture of Bowdoin College, that it was not always the case. During the early 19th century at Bowdoin and other colleges across America, “physical endeavors were considered ungentlemanly and antithetical to academic pursuits” (Anderson 85). In fact, up until 1820, when a system of German gymnastics was implemented, most colleges had passed a prohibition of athletics. Anderson describes that the integration was slow: in the 1850s, “athletics” was mainly focused on outdoor activities such as gardening and gymnastics. As larger universities, such as Harvard and Princeton, began to establish programs, “physical education, physical culture, and hygiene entered the college curriculum, became requirements, and received credit toward the degree” (Anderson 85). It was not until the 1870s and 1880s, Anderson explains, that explicit gymnasiums were ever built.

Sargent Gym, heliotype architectural plan, Rotch and Tilden Architects, 1886. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

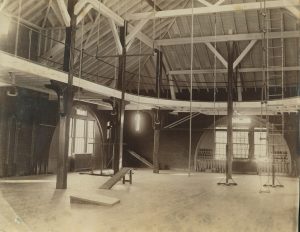

By 1872, physical training became mandatory for Bowdoin students, and the unfinished Memorial Hall started to be used as a gymnasium in 1873. Once the building was completed, the gymnasium was moved to a space in Winthrop Hall. It was clear that, despite what little existed of the athletic department, a new building was necessary. An alumnus, Dudley Sargent, was supportive of the endeavor and promised to provide the new space with a gymnastic apparatus. The building was completed in November 1886 at the cost of $11,789.08 (Anderson 86). While there was excitement on campus about the new building, Anderson writes: “In the hierarchy of college buildings, a gymnasium does not occupy a position consonant with the importance to undergraduate life” (86). The building stood behind the main college row facing west and was designed by architects Rotch and Tilden of Boston, and their institutional designs were known to be done with stone or brick— “appropriately more compact, broad, and earthbound” (87). Merely ten years after its construction, it became clear that not only was the student body size increasing, but the college required a central heating plant. A small addition was added to the building, as was a smokestack, but the upper floor was still used as a gymnasium.

Exterior of Old Sargent Gymnasium looking East, 1886. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

Interior of Old Sargent Gymnasium with athletic equipment, 1886. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

Eventually, the College needed to build yet another, even bigger gymnasium separate from the heating plant building. When the new gymnasium was finally complete, questions arose about how the spare space in the heating plant should be used. According to an article from the Bowdoin Orient from January 7, 1913, the Y.M.C.A. proposed that the old gymnasium be used for the Brunswick Boys’ Club. This proposal was temporarily passed, and they organized and held classes every afternoon from 4:30 to 5:30 p.m. The College saw this as an opportunity to give back to the community, as the town of Brunswick did not have a building big enough for their group meetings. The club did not meet there for very long, though, as Anderson writes in her book that in 1915, the old Sargent gymnasium was converted into a student union; but by 1920, the building was fully taken over and used as a heating plant, and it remains to this day.

Heating Plant. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

Part of what is fascinating about the transformation of the first Sargent Gym into its current use as a heating plant is that relatively few people on campus seem to be aware of its history. This provides an interesting perspective when it comes to memorialization and lack thereof. There are no plaques on the building now even hinting at its use as a gymnasium, or briefly as a student union, in the past. Instead of outwardly memorializing the space superficially, Bowdoin has merely found another use for it. This, in some ways, is a form of subtle, productive commemoration—appreciating a site not by preserving it but by utilizing it. The building today, while slightly different, still maintains the original form that Rotch and Tilden designed. After a fire upstairs, the windows and roof had to be replaced, and, of course, a smokestack has been added for the heating plant. All and all, though, a sliver of Bowdoin’s athletic history has been subtly maintained. Despite its relatively old age, the building has not been torn down, and the little-known memory of the first Sargent Gymnasium quietly lives on.

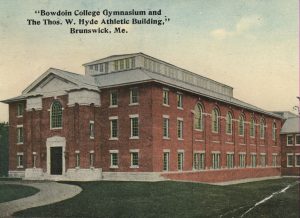

Hyde Athletic Building, Sargent Gym, and Smith Student Union

Planning for a new gymnasium to replace the heating plant took nearly a decade. The new plans departed from the style of the first Sargent Gymnasium “and used instead classical details derived from Renaissance and Georgian repertoires” (Anderson 90). Generous donors, such as John Sedgwick Hyde and George Sullivan Bowdoin, gave money towards the new gymnasium, and the undergraduate and medical students contributed more than $9000. The building was ultimately finished in 1913 under the architectural firm Allen and Collens, and they were known to be one of the only groups able to integrate so many historical styles into the design. Anderson writes on the design:

Postcard of the exterior of Hyde Athletic Building, 1913.Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

“Perhaps the best element of the design is in the monumental entrance pavilion. The central projecting bay comprises a frieze and a triangular pediment supported by brick pilasters and framing an arched window over a classically inspired door. Inscribed within the pediment is the Bowdoin sun. While the door is reminiscent of the Greek Revival, the window above is Federal” (90-91).

Interior of Hyde Athletic Building/Sargent Gymnasium with students practicing fencing. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

The new building took the name of Sargent Gymnasium and General Thomas Worcester Hyde Athletic Building. The new structure had two sections: a gym and an athletic building with an elevated indoor track and the main ground floor which would be used for baseball and field sports. On January 7, 1913, the Bowdoin Orient wrote that: “The General Thomas Worcester Hyde Athletic Building is the largest structure in New England devoted exclusively to athletics.” The students were extremely proud of the new building and were excited that spring sports could get a headstart on training by using the indoor venue. The athletic facility was used for many years, and additions were added over time: Curtis Pool was built next door in 1927, and Morrell Gym was added later in 1965.

Colored postcard of the Hyde Athletic Building interior. There is a Bowdoin banner on the far wall, and students in the foreground are preparing for a track event. Bystanders are in front of the bleachers and on the bleachers, 1917. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

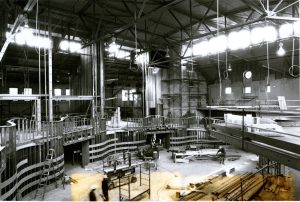

Approximately eighty years after it was built, the growing student body again outgrew Hyde Athletic Building. In 1993, the decision was made to convert the previous Hyde Cage into the David Saul Smith Union. The building offered a much bigger space than the previous Moulton Union, and so construction began that year. The firm in charge of the project, Barba and Wheelock Architects, wrote in their summary of the project:

Groundbreaking ceremony for the renovation of Hyde Cage athletic facility into David Saul Smith Union, 1993.Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

“The new design preserves all the original features that define the architectural enclosure: perimeter brick walls, regularly-spaced, paired windows, a clerestory monitor and exposed metal trusses – yet introduces new spaces for activities around a center gathering space that also serves as performance space. The central space is surrounded by a spiral ramp that engages the entire space. The Campus Center includes public gathering areas such as a café, pub, game room, mailroom, campus services and college store” (Barba and Wheelock).

The architects and college continued the theme of preserving the building’s original structure, as they did with the original Sargent Gymnasium. The idea of reusing materials and spaces appears to be a common thread throughout the Bowdoin community; the December 3, 1993, issue of the Bowdoin Orient stated that:

“As construction of the David Saul Smith Union continues, there have been numerous requests by faculty and staff for the surplus wood being removed from the old Hyde Cage running track. Unfortunately, none of this wood can be made available to the public. Some of the wood will be reused in the project, and some will be used elsewhere by Physical Plant” (Orient, VOL. CXXIV, December 3, 1993, No. 11, pg 5).

Renovation of the indoor athletic facility, Hyde Cage, into the David Saul Smith Union, 1994. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

Renovation of the indoor athletic facility, Hyde Cage, into the David Saul Smith Union, 1994. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

This demonstrates the collective attitude of letting no materials go to waste. By converting the Hyde Cage into Smith Union, the College continues to let the memory of the previous athletic facility persist. Similar to the Heating Plant, the building’s past is not blatantly apparent. Yet, its subtlety is what makes its form of commemoration remarkable. When standing in certain spots in Smith Union, its vastness strikes you as unique, and that is in large because of its athletic history. On one wall on the ground floor, a marker for the 800 meters on the track remains painted on the wall. The structure continues to be appreciated as it lives out its construction’s initial intention: to be a functional space for Bowdoin College students. By standing in David Saul Smith Union, one is struck by a connection to a deeper history. Knowing that Bowdoin students participated in athletics on the same floor and under the same roof a hundred years prior, the renovation of Hyde Athletic Cage offers an intimate closeness and sense of community to anyone who enters its doors.

The Completed David Saul Smith Union, 1995. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

- One of the few reminders left in Smith Union of the building’s history as the indoor track. Courtesy Professor Jennifer Clarke Kosak.

- Mark for the start of the relay on a Smith Union wall. Courtesy Professor Jennifer Clarke Kosak.

- Partially covered up by what is now a staircase: start of the 200 on the previous Hyde Cage track. Courtesy Professor Jennifer Clarke Kosak.

Curtis Pool and Studzinski Recital Hall

By the 1920s, Bowdoin’s desire to build a swimming pool was mounting, and with the help of a generous donation from Cyrus Curtis, its construction commenced in April 1927. It was decided by the architects and Athletic Committee that the building would be attached to Sargent Gymnasium. Patricia Anderson writes:

Curtis Pool, circa 1928. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

“Unlike the Sargent Gymnasium and Hyde Athletic Building, the Curtis Pool structure is not pretentious. McKim, Mead and White designed a graceful rather than monumental entranceway […] The Curtis Pool building is gracious; its ample and well-proportioned fenestration conveys a lightness appropriate for swimming” (Anderson 99).

When, yet again, Bowdoin’s size outgrew the pool by the early 2000s, the College built a new facility on the other side of campus that would be big enough, the Leroy Greason Pool. In keeping with the theme, the previous structure which housed Curtis Pool was not torn down; it was instead renovated and repurposed as another space for student use. Central to the main campus, Curtis Pool was renovated into a new 286 seat recital hall that was completed in May 2007. Its construction cost $15 million, and it is now known as Studzinski Recital Hall.

Renovation of Curtis Pool into Recital Hall. Courtesy William Rawn Associates.

The architect’s review of the renovation echoes the sentiments expressed about converting Hyde Cage to Smith Union:

“Transforming the Curtis Pool brings new life to this long dormant campus landmark, and perhaps more significantly, it preserves Bowdoin’s extraordinary collection of McKim, Mead and White Buildings (over a dozen buildings). The decision to reuse the existing structure rather than constructing a new building on the periphery of campus provides a prominent central location for the Recital Hall, appropriate to its role in uniting Bowdoin’s campus community” (William Rawn Associates).

When standing at the top row of seats in the new hall, you can get the chills when imagining the building’s past. The pool’s imprint almost haunts the recital hall like a ghost—the knowledge of its previous use permeates the beauty and tranquility of the new space. Yet again, the renovation of the building allows participation into a collective memory of Bowdoin, particularly in regards to college athletics.

Studzinski Recital Hall. Courtesy William Rawn Associates.

Hubbard Grandstand and Whittier Field

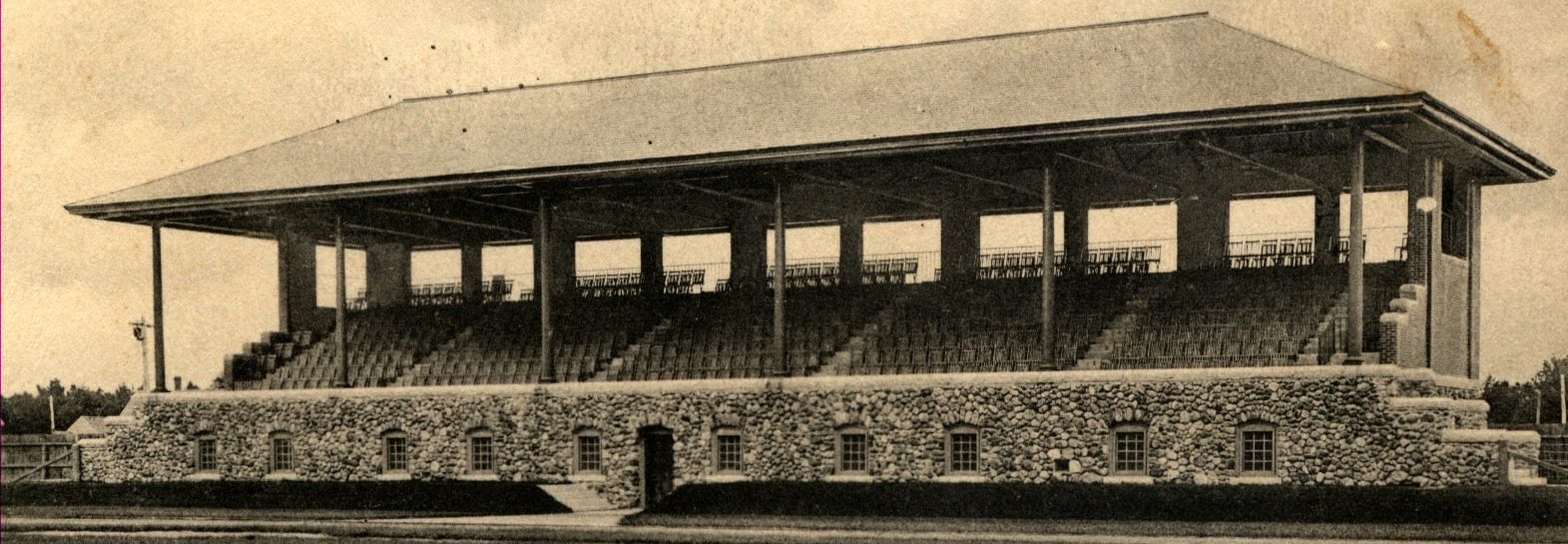

South view of Hubbard Grandstand. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

By the early 1890s, it was clear that the College required a proper playing field and track. Anderson sites a brochure entitled The Proposed Athletic Field at Bowdoin College, which highlighted the dangerous conditions of the original field and called for donations for the making of a quarter-mile track, baseball and football fields, and a grandstand with dressing rooms for players. The area was engineered by John Emerson Burbank, a Bowdoin graduate, and William Muir Jr. was the contractor (Anderson 183). Anderson writes that: “Across the country at this time, competitive sports had developed to the point where grandstands and stadiums were needed for spectators” (183). The field was completed in 1896 and named after Frank Nathaniel Whittier, the director of athletics.

View of Hubbard Grandstand (dedicated 1904), in front of Whittier Field, to the east of campus. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

In 1902, an alumnus from the class of 1857, General Thomas H. Hubbard, gave a generous gift to fund a grandstand that would have locker rooms and showers. Henry Vaughan, who was the architect of both Hubbard Hall and Searles Science Building, took on this project, although he departed from the Gothic themes of the other two buildings, “he turned to something more pastoral,” Anderson writes, “related to large summer cottages and Steven’s Shingle style, although the grandstand is made of stone and brick” (184).

In General Hubbard’s 1904 dedication of the grandstand, he began:

“Today we give this structure to Bowdoin College and dedicate it to the use of athletes and the lovers of athletics. Let us at the same time dedicate it to the declaration, ‘Fair play, and let the best man win’” (184).

Exterior view of Hubbard Grandstand and Whittier Fields, showing a baseball game against U-Maine, 1905. Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

These very words Hubbard used in his dedication are carved on the granite plinth that lies at the front of the grandstand. Today, Hubbard’s message and grandstand still face the field, serving as a connection to Bowdoin’s past athletic history. In 2017, the historic Whittier Field Athletic Complex was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The worn stone seats of the grandstand are a reminder of the longstanding tradition of supporting and spectating Bowdoin athletics.

Over the years, modifications have been made to the field and grandstand: artificial turf and a larger track were installed, more bleachers have been added on the opposite side of the field, and the press box was modified after a small fire, but the heart of the building remains the same.

Whittier Field and Hubbard Grandstand. Courtesy Bowdoin Athletics.

Stone engraving on the Hubbard Grandstand. Courtesy Professor Jennifer Clarke Kozak.

Works Cited

Anderson, Patricia McGraw, "The Architecture of Bowdoin College" (1988). Bowdoin Histories. 3.https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/bowdoin-histories/3 “Bowdoin College: Recital Hall Renovations: William Rawn Associates.” Bowdoin College | Recital Hall Renovations | William Rawn Associates, rawnarch.com/bowdoin_renovatio. https://rawnarch.com/bowdoin_renovations “Bowdoin College - Smith Union.” Barba Wheelock Architects, 30 Mar. 2018, www.barbawheelock.com/portfolio-posts/bowdoin-college-smith-union/. http://www.barbawheelock.com/portfolio-posts/bowdoin-college-smith-union/ George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine. The Bowdoin Orient, "Bowdoin Orient v.42, no.1-30 (1912-1913)" (1913). The Bowdoin Orient 1910-1919. 4. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/bowdoinorient-1910s/4 The Bowdoin Orient, "Bowdoin Orient v.124, no.1-23 (1993-1994)" (1994). The Bowdoin Orient 1990-1999. 6. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/bowdoinorient-1990s/6