“Can I Make Any Difference?” Gang Affiliation, the School-to-Prison Pipeline, and Implications for Teachers by Kayla Gass and Judson Laughter

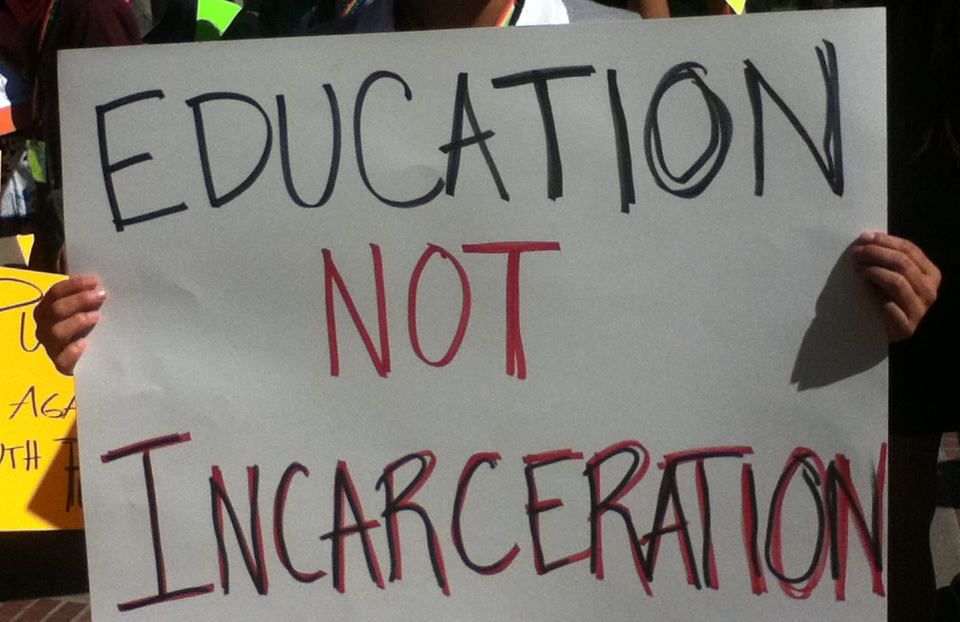

In “‘Can I Make Any Difference?’ Gang Affiliation, the School-to-Prison Pipeline, and Implications for Teachers,” authors Kayla Gass and Judson Laughter talk about the intersections between gang affiliations and correctional facility engagement among urban youth. Both authors endorse an appropriate scholarly remark when they cite, “‘priorities to incarcerate compete against priorities to educate’ (Toldson & Morton, 2011, p. 2)” (Gass and Laughter, 334). Furthermore, they explain how the school-to-prison pipeline has been closely related to gang affiliations since the beginning of the negative institutional trend (Gass and Laughter, 335).

The article focuses on a group study done by some academics, who want to seek remedy for students that seem vulnerable to the gang-affiliated lifestyle. However, the authors note how “only six [of the ten students participated in the questionnaires about their associations with gang and academic lives] with minimal responses. The students were unwilling to participate because they thought the activity was going to be used for “snitching,” or giving the administration or school resource officer information that the students did not want others to know” (Gass and Laughter, 339). So, the student became slightly flawed due to its low number of participants and limited control of settings. So ultimately, Gass and Laughter close their article with the statement, “While there is a need to attack the school-to-prison pipeline as a hegemonic system, there is much that can be done in the classroom by an individual teacher. The school-to-prison pipeline works when students do not see school preparing them for anything but prison” (Gass and Laughter, 343). So, this article becomes very significant when brainstorming possible solutions to this unfortunate pattern in American society.

Why Black Lives (and Minds) Matter: Race, Freedom Schools & the Quest for Educational Equity by Tyrone Howard

In this article, scholar Tyrone Howard explains the significance of not only focusing on the notion of black lives, but rather the additional importance of including a pursuit to the development of black minds. Therefore, he starts off the article with a segment that praises the work done by the movement of Black Lives Matter (BLM). As Howard explains, “Black Lives Matter is used as a backdrop for this work because it is through the spirit of engaging in actions that help to reclaim humanity and dignity for the education of Black children that is critical in today’s given context” (Howard, 102). So, the work of Black Matters Lives, regardless of the area of black life that is being improved, subsequently improves the daily life of black students within the city. The article puts a strong focus on black students because according to Howard, “The level of scrutiny for Black children usually starts early, occurs frequently, and tends to intensify over time” (Howard, 102). Furthermore, “the criminalizing of students in learning spaces was officially sanctioned, and Black children became “public enemy number one” in many schools across the nation.” (Howard, 103); therefore, both putting black students at the “greatest risk of being funneled into the school-to- prison pipeline” and making black students “40 percent of students who received one or more out-of-school suspensions” (Howard, 106). Out of their 18 representation in the national public school population (Howard, 106). Such a trend and target towards black children end up making them “32 percent of children arrested and 40 percent of all children and youth in residential placement in the juvenile justice system” (Howard, 106).

Overall, Howard tries to put together a study that exhibits a program that has proven to fight this effort to send black students to prison through systematic means. He introduces the readers to a program called Freedom Schools which “provide[s] a way of reimagining schools where students are seen through a much more humane prism built on equity, acceptance, and fairness; something many of the students do not experience in their traditional schools” (Howard, 107). He notes how the program has had positive improvement on many areas of black life, far beyond the classroom. The program also attacks the efforts being made to police black children by projecting how policing efforts of black children can lead to “lower educational achievement, higher unemployment, higher alcohol and substance abuse, increased mental health problems, and higher rates of learning disabilities (Aizer & Doyle, 2013)” (Howard, 106). And finally, he concluded his article with the emphasis that “Black minds require care, concern, and proper cultivating from educators at all levels. There needs to be an unapologetic and explicit focus on the most scrutinized and marginalized students in schools. The transformation of learning spaces from criminal focused environments where students’ humanity is affirmed is long overdue for all students in schools” (Howard, 111).