Five Years Later

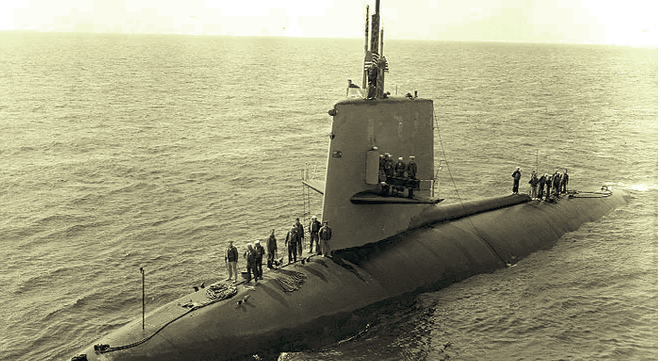

In 1968, a Skipjack-class nuclear submarine, the USS Scorpion (SSN-589), was patrolling for Soviet activity off of the Azores. The Skipjack-class was not quite up to par with the technology in the Thresher-class submarines, but their teardrop hull and speedy, efficient design posed a serious threat to the Soviets.

YouTube: “Uncle Sam proudly welcomes Skipjack!”

Just one year earlier, the non-stop action that was required of the Scorpion had taken a toll on its capabilities, so much so that crew members had begun to refer to their boat the “Scrapiron.” A significant overhaul of its systems and machinery were in rapid need. However, following the tragedy of the USS Thresher, the newly implemented safety protocols required 36 months in vetting, a dramatic increase from the 9 month required prior. As a result, the US Submarine Force Atlantic officers gave orders for the Scorpion to undergo only emergency repairs rather than full revamp.

On May 27th, the officers back in Norfolk would be questioning their decision to cut down on repair time when the USS Scorpion failed to turn up on time back at the Norfolk Navy Yard. Last heard from on May 21st, the boat was long overdue and all calls to the Scorpion’s call sign “Brandywine” went unanswered. Along the 3,300 mile route from Spain to Norfolk, the whereabouts of the Scorpion were unknown. In addition to the tense families eager to reunite from their loved ones aboard, officials were concerned about the status of the Scorpion—particularly because of the nuclear technology on board.

The Navy brought in Dr. John Craven, the chief civilian scientist of special projects, because of his specialty in Bayesian Search Theory, which used math to triangulate lost objects. Craven used the sounds from the hydrophone log from off of the coast of the Canary Islands and Newfoundland and he connected these readouts to find a series of explosions at roughly 11,000 below the surface. This was far lower than the submarine could tolerate, further elevating concern for the sub. On June 5th, the Navy announced that the Scorpion was lost and a search for the wreckage was launched.

The Mizar, the search vessel, conducted a sweep of the ocean floor with cameras in tow at the spot of the first detected explosion, but nothing turned up. Craven and his team had a theory for the new search spot. He noted that the Scorpion was headed in the opposite direction at the time of the explosion. The most probable cause of this direction change was that a torpedo charge had been launched onboard leading the sub to do a 180-degree pivot in an attempt to avoid a collision. This result would lead the Scorpion’s crash location to be east, instead of west, of the crash location. Despite skepticism from officers, a search was conducted to the east of the crash site and the Scorpion’s remnants were found. Once these revenants were found, all 99 members aboard the Scorpion were pronounced deceased.

Despite the extensive investigation, there has still been no conclusion regarding the Scorpion’s fate. This is partly due to contradicting evidence regarding the damage and the Navy’s hesitation towards accepting that their crew may have been killed by their own weapons.

The legacy of the accidents

Since the investigation in 1968, there have been zero accidents aboard nuclear submarines in the Navy. The disaster aboard the USS Thresher and USS Scorpion served as a wake-up call to the consequences of poor safety measures leading Rickover to reevaluate processes in place. The outcome was the Submarine Safety Program, also known as SUBSAFE. This program focuses on the entire lifespan of a submarine, including the design, build, operation, and maintenance. This risk mitigation program has proven so effective that not a single submarine has been lost since implementation.