I have always found the 2011 disaster at Fukushima fascinating because people seem to have a poor understanding of the actual fatalities. When I have asked my friends and family how many people died in the Fukushima Nuclear meltdown, their answers generally fall in the thousands or tens of thousands. In reality, there have been no or very few deaths associated with the meltdown, but the tsunami (and earthquake) killed around 20,000 people. For reasons mentioned in the other sections of this website, our historical memory of this event focuses on the nuclear meltdown. This instance of biased remembrance brings up interesting questions about our perceptions of risk. I suspect that the fact that there have been so few large-scale nuclear disasters while tsunamis and earthquakes are more common also plays a role. In this section, I will provide some contextual background on nuclear power and Japan’s nuclear history in order to critically examine ordinary people’s perception of nuclear risk.

Nuclear Power

The nuclear power industry is controversial and has suffered a few major incidents in recent decades. Nuclear power is a contentious energy source for a few reasons, one of the most salient being poor knowledge of radiation. Radiation is a terrifying threat because you can’t see it and few

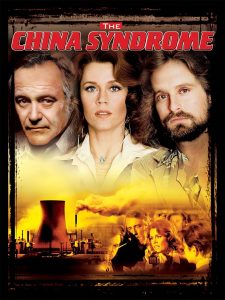

understand it, therefore people are very susceptible to media influence and fear about nuclear power and radiation. An interesting example of this is the movie “The China Syndrome”, which was released in the US twelve days before the Three Mile Island (TMI) disaster occurred (Chernov and Sornette 2016, 31). The movie followed a fictitious accident at a nuclear plant and a subsequent investigation that unveiled numerous cover-ups in the construction and operation of the plant (Chernov and Sornette 2016, 31). When TMI happened, “Many of the 400 reporters […] were under the influence of this movie”, and the movie likely compounded the public’s loss of faith in nuclear power (Chernov and Sornette 2016, 31). The public’s lack of knowledge, which is discussed in the Radiological Response section, causes them to assume the worst.

Japan’s History with Nuclear

Japan has a storied history with nuclear power. After “the destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima by nuclear weapons, the Japanese population vehemently opposed all use of nuclear power in their country” (Chernov and Sornette 2016, 137). As a result, the Japanese government made a habit of downplaying the risk posed by nuclear power, going so far as to claim “‘absolute safeness’” whereby there is “‘no risk that something could go wrong’” (Chernov and Sornette 2016, 137). This is an example of a long history of poor regulation and neglect that I will not analyze on this website.

From the perspective of the Sohyo Union and Japan Socialist Party (JSP), the main factor in Japan’s anti-nuclear sentiment is the connection between nuclear power and nuclear warfare (Suzuki 2016, 605). Rengo, a dominant union in Japan, was strongly pro-nuclear energy in the 2000s (Suzuki 2016, 607); however, following the Fukushima meltdown, they transitioned to a policy classifying nuclear power as safe and useful in the short-term but advocated for Japan phasing out nuclear energy in the long run (Suzuki 2016, 608). Such an approach seems incredibly counter-intuitive to me – fear is often heightened immediately after a disaster, so a policy of temporary closure until we have a more solid understanding of the technology is a more logical approach.

Reactions to 2011

Many reactions to the 2011 disaster are littered with disappointment, implicit in this that someone should have been better. On March 15th, a Japan Times op-ed titled “Nuclear power in Disarray” harshly assigns blame for the Fukushima disaster and calls for “more reliable” safety measures. (The Japan Times 2011). The unnamed author blames the government and power industry, saying that the two have “failed to implement necessary safeguards” (The Japan Times 2011). As a specific example, the author claims that having one back-up diesel generator is not enough, a policy of double-redundancy must be adopted (The Japan Times 2011). If there had indeed been two sets of back-up generators, I wonder if the author would have made the exact same claim, calling for a triple-redundancy system. The op-ed author writes “it is mind-boggling that such flawed policies were in place”, but I find it mind-boggling that the author expects every risk be entirely mitigated (The Japan Times 2011). For example, the seawall around the Fukushima plant was designed to protect against a 5.7m tsunami and simply could not withstand the 15m one that arrived (Chernov and Sornette 2016, 133). While action was taken to prevent some disasters, only certain outcomes were predicted; this is further examined in the Risk Perception section.

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission similarly concluded that the accident “‘could and should have been foreseen and prevented'” (Chernov and Sornette 2016, 135). In contrast, after thorough analysis of different nuclear technologies, Filburn and Bullard claim that “The magnitude of the 2011 Great Japan earthquake and tsunami would likely have overwhelmed any nuclear plant at the Fukushima site, regardless of their underlying design” (Filburn and Bullard 2016, page 119). It is unreasonable to think that humans could have prevented this disaster, and not necessarily fruitful to ponder why we could not. In the same paragraph, Filbrun and Bullard write that “The regulating authority and the utility also had warnings that the tsunami preparations at Fukushima Daiichi were inadequate” (Filburn and Bullard 2016, page 119). This is precisely the fascination of risk; we can simultaneously recognize that there is only so much we can do, yet we never stop believing that we could have and should have done more. These ideas are explored further in the Risk Assessment Section.

According to the author of the Japan Times article mentioned above, the declaration of a state of emergency “[destroys] the credibility of the claim by the government and electric power industry that nuclear power generation is safe” (The Japan Times 2011). But what does “safe” mean? We do unsafe things every day, yet a host of factors addressed in the Radiological Response section explain why nuclear disasters may appear to pose a greater risk (involuntariness, government/corporate involvement, etc.). The context provided in this section is meant to illuminate the inconsistencies and complications in our perception of nuclear risk. In a similar manner, the Risk Assessment Section walks through just how difficult it is to assess risk associated with nuclear power.