Radiological emergencies carry a plethora of unique problems. Given the general public’s poor understanding of radiation and its risks, the media plays a crucial role in this type of disaster. Robertson and Pengilley emphasize the necessity of effective communication and explain that the media often focuses on the worst possible outcome (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 693). This section contains an analysis of several articles from The Japan Times that were published as the disaster unfolded.

Before examining the primary sources, we must develop an understanding of radiation danger and possible treatments. One notable treatment to radiation contamination is the usage of potassium iodide (KI) pills. In essence, KI pills saturate the thyroid glands with harmless iodine to prevent harmful iodine from collecting. However, it is critical that these pills only be used for severe internal contamination; if taken by someone who is at low or zero risk for radiation exposure, they can have harmful side effects. It is easy to label fearful behavior as irresponsible in retrospect, but an examination of media sources can illuminate the confusion circulating in the days following the disaster. In this analysis, I will use messaging around KI pills as a lens through which to emphasize the uncertainty that was created by conflicting media reports.

March 14th

On March 14th, an article titled “Radiation poses range of health problems” appeared. It discusses how the potential health effects from nuclear power plants range from toxic radiation poisoning in workers to increased cancer rates (Stein 2011). The article, written by Rob Stein of The Washington Post contains conflicting messages that must confuse readers. From a random selection of patients who could have been exposed to high doses of radiation, on March 14, “None had yet shown physical symptoms of radiation poisoning” (Stein 2011). In the same article, it is mentioned that “Japanese officials announced plans to distribute KI pills, which block radioactive iodine from accumulating in the thyroid glands” (Stein 2011). An announcement about the governmental distribution of iodine pills appears in the first paragraph, immediately followed by “Government officials stressed that the amount of radiation that had been released […] appeared to be relatively low” (Stein 2011). As mentioned above, reporting about KI pills in areas with low radiation risk can become a “public health issue” because people may take the pills and experience harmful side effects (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 694). Robertson and Pengilley specifically state that KI pills should not be given to low-risk populations, especially “on a precautionary basis of for phycological reassurance” (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 694). Unclear messaging from the media may exacerbate fear and cause inappropriate usage of KI pills.

March 16th

On March 16th, two more articles appeared. On page 2 of The Japan Times, a Q&A titled “Take proper steps to avoid exposure to fallout” was published by two staff writers, Tomoko Otake and Setsuko Kamiya (Otake and Kamiya 2011). Two of the questions address iodide pills. In response to what to do if you inhale radioactive iodine, Otake and Kamiya write “In a case of internal contamination with radioactive iodine, it is important to take iodine pills that help protect the thyroid gland” (Otake and Kamiya 2011). They do note that the pills are only effective for internal iodine contamination and must be prescribed by a doctor, but there is no discussion of what internal iodine contamination means or who might be susceptible to this (Otake and Kamiya 2011). To a reader with little knowledge about the science of radiation, such wordings and suggestions are likely to instill fear.

In response to whether disinfectants can be substituted for iodine pills, Otake and Kamiya write “Although disinfectants and gargles contain potassium iodine, NIRS warns people not to use them because they are ineffective”, only later stating that “both products contains other ingredients that can harm the body when consumed” (Otake and Kamiya 2011). The article suggests that the primary reason not to consume disinfectants, which often contain toxic ingredients, is because they would not be effective, not because they are toxic. Only at the end of the article is there a discussion of actual radiation exposure in various areas and advice about how to understand and contextualize the numbers. This Q&A does not provide enough scientific information to suggest that people take KI pills; such a statement should only be accompanied with a clear and detailed explanation of appropriate usage.

A second article from March 16th is titled “West Coast facing nuclear cloud?” and indicates how the radiological hysteria spread across the Pacific Ocean to the U.S. (AFP-JIJI 2011). The scientific consensus was that the West Coast was not in danger of receiving significant radioactive material, but this article’s comparison to Chernobyl and how quickly radioactive material spread across the globe then counteracted any realistic presentation of the risk (AFP-JIJI 2011). “While radioactivity could reach the United States from the quake-hit plant, the levels would not be high enough to cause major health problems, said the Nuclear Regulatory Commission […] even Hawaii faces little risk” (AFP-JIJI 2011). Ambiguous language like “it’s quite possible” but probably not harmful will only alarm uneducated readers (AFP-JIJI 2011). It is mentioned that Californian officials are “‘monitoring the situation closely'”, only increasing fear that something terrible could happen (AFP-JIJI 2011). The choice to include such a statement will have no effect other than to alarm Californians about the high stakes of the situation. Could they not have just said “there is very little to no risk posed to the Western US”? Articles like this one not only support people’s fear about the possibility of extreme scenarios, they bring them to the front of the conversation, making way for further discussion.

Fear In California

Robertson and Pengilley discuss how articles like this promote unsafe behavior: “The widespread sale and inappropriate use of potassium iodide in California after the Fukushima incidents highlights the dangers of such reporting (Roberston and Pengilley 2012, 693). In California, a place not in danger of being affected by the nuclear events in Japan, experienced a significant increase in sales of Potassium iodide pills (Myers 2011). Since these pills are available over-the-counter in California, public health officials had to step in because “cases of acute toxicity were being reported by poison centers” (Roberston and Pengilley 2012, 694).

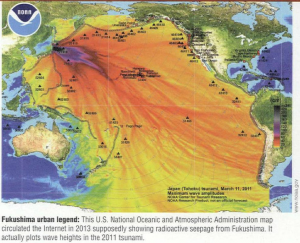

Below is an image that circulated widely during the crisis and was used to show the spread of radioactive material reaching the West Coast of the U.S. (Terrell 2014). In reality, the chart is clearly labeled and measures sea surface height. Thus, it is true that California may have seen an incremental increase in wave amplitudes from the tsunami, but this chart is in no way connected to radiation. Examples like this indicate how important effective communication and control of the media is. It must be mentioned that there were certainly news outlets trying to accurately state the low risk faced by California (see Barboza 2014 or Revkin 2014), but it only takes one alarming report for panic to explode. A simple mention of something can quickly get out of hand and result in widespread fear and panic.