In a nuclear accident, there are two main categories of health risk. There are the physical dangers (consequences of explosions, radiation poisoning, cancer, etc.), and there are the mental risks that can have tangible physical effects. In this section, I will discuss the psychological effects of a disaster like Fukushima and discuss critical aspects of an effective response effort.

Addressing a Population

Robertson and Pengilley categorize people involved in a radiological emergency into three groups: those who are severely affected by radiation (need protection, medical help, etc.), those who received measurable doses of radiation but are not vulnerable to short/medium-term health problems, and those who received no radiation exposure form the emergency but are psychologically affected by their perceptions of risk (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 690). The first group is often dealt with by medical professionals and scientists; the second and third groups must be carefully managed by public health agencies to avoid unnecessary anxiety and widespread panic (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 690). Following Chernobyl, studies have indicated increases in suicides and abortions, emphasizing the lasting impact that nuclear accidents can cause (Stein 2011). Chernobyl is known to have spurred increases in cancer, yet the World Health Organization (WHO) has shown that, even then, “mental health was the most serious public health problem” (Yoshida et al. 2016). While not spectacular and physical, mental and emotional effects cause measurable harm.

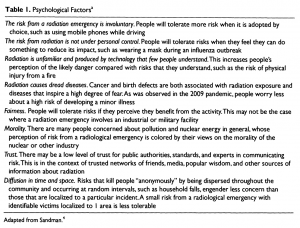

Psychological Factors

Since it is possible to precisely measure radiation in small amounts, most of what public health officials must deal with in low-risk populations is psychological effects (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 691). Table 1 lists relatable reasons why radiological emergencies cause significant psychological damage. Robertson and Pengilley clearly explain how response to fear is a major player in situations like this: “[people] believe that their actions are the way to control a threat to their safety” (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 691). The general population has an incredibly poor understanding of radiation and the risk it poses; this makes effective communication by public health officials critical (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 693). Fear of involuntary risk, the very first entry in Table 1, is a logical and human response to lack of control. For example, people choose to drive which allows them to feel control over the risk, yet driving is one of the most dangerous things Americans do. When risk is involuntary, as it is in a radiological emergency, people are much less tolerant of government disorganization and inaction.

Evacuations

Uninformed decisions that result from unnecessary anxiety, often in the context of self-evacuation, can be deadly. Evacuations are meant to decrease overall risk, but if poorly executed, they can only exacerbate a disaster. For example, after 9/11, thousands are lives are thought to have been lost by peoples’ choice to travel by road instead of by air (Roberston and Pengilley 2012, 690). In radiological emergencies, public perception of radiation risk may be much higher than the actual risk of an evacuation (Roberston and Pengilley 2012, 695); thus it is critical to accurately portray risks and manage a population in the event that an evacuation is possible. After Fukushima, public health agencies were able to prevent an unnecessary mass self-evacuation of Tokyo by providing citizens with clear information about how to best protect themselves (Roberston and Pengilley 2012, 695).

Risk Communication

Robertson and Pengilley also offer specific advice in their calls for effective communication. Pregnant women must be directly addressed because of perceptions of infant risk – although there was unlikely cause for concern in Fukushima, clear data must be provided because pregnant women are likely to be concerned (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 693). Food and water risk communication is especially important and must be addressed frequently. If there are low levels of contamination in food and water, it can be useful to say someone needs to eat a certain amount of a normal food to get the same dose to contextualize the risk (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 693-4).

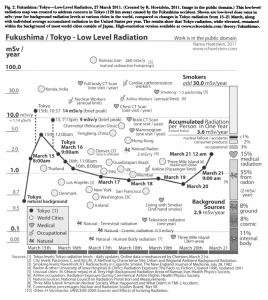

The general public struggles to understand mathematical abstractions or units of radiation measurements, so it is helpful to compare a dose to everyday activities (Robertson and Pengilley 2012, 693). Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. Rama Hoetzlein attempted to contextualize radiation risk surrounding the Fukushima disaster in a digestible way and produced the figure below (Hoetzlein 2012, 116). While the image offers useful comparisons to show that Tokyo did not experience alarming radiation levels, it is still incredibly complicated and difficult to read. It is possible to pick out useful benchmarks, like the fact that residents of Denver, CO experience higher radiation every day than residents of Tokyo on most days around the accident, but reading a chart like this requires a basic scientific understanding that should not be assumed.

Resolutions

In response to the problems with risk communication, Gariel et al. call for a “‘practical radiological protection culture'”, defined as the “knowledge and skills that enable affected populations to make choices and to behave wisely in situations involving exposure to ionizing radiation” (Gariel, Rollinger, and Schneider 2018, 256-7). Such a culture allows people to interpret various types and levels of exposure in a productive way (Gariel, Rollinger, and Schneider 2018, 258). Gariel et al. discuss post-Fukushima recovery and the role of both the public and the experts. Japanese experts largely recognized the importance of dialogue with affected people to restore trust and provide information; however, “although radiation protection is necessary, it cannot rule people’s lives” (Gariel, Rollinger, and Schneider 2018, 256-7). A balance must be struck between living life and mitigating all risk, and the ultimate goal should be for people to be able to make their own risk management decisions. The culture that Gariel et al. call for is one in which people “build their own benchmarks against radioactivity” (Gariel, Rollinger, and Schneider 2018, 258). As mentioned above, the public’s poor understanding of radiation means that developing ways to contextualize radiation risk is critical.

Many factors must be considered in a radiological emergency. The effects from the spectacle must be immediately addressed, but the psychological harm and risks are not to be ignored and must be combatted with effective communication. Accessible information from experts and important actors must come frequently. Furthermore, people need to feel like they have agency and some degree of control. Numerous studies have showed quantifiable psychological harm caused by Fukushima; thus, the mental and emotional risks must be incorporated into any effective radiological response.