Between the years of 1959 and 1962, an estimated 36 million Chinese citizens died of.1Yang Jisheng, Tombstone (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2012), 12. Tens of thousands of people ate anything that resembled food: raw seeds, tree bark, and even dirt. And thousands of others resorted to cannibalism, eating the remains of fellow villagers and even family members.2Jisheng, Tombstone, 14. Much—if not all—of this tragedy can be attributed to Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Great Leap Forward. The Great Leap Forward was a concerted effort to catapult China into the global, industrialized world in just a few years by using millions of Chinese hands to produce massive qualities of steel rather than purchasing heavy machinery.3Britannica, “Great Leap Forward” (website), accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Leap-Forward. Alongside the increased demands for steel, however, the CCP needed to provide food for all of its citizens. This became an increasingly difficult task as the government forced stricter communalization laws. Exacerbated—but not caused—by natural disaster, the Great Chinese Famine can be attributed to a few primary institutional causes: radical grain targets and procurement; authoritarian control over food stores; and ineffective farming strategies.

At the start of the Great Leap Forward, the Chinese Communist Party seized all private property and abolished all private food production; as a replacement, the CCP established People’s Communes in all rural regions that facilitated both the production and distribution of grain. This abolition was done without much foresight, however, as around that time about 80% of all grain was produced by private farms, and the newly instituted communes planted less grain than those farms previously had.4Vaclav Smil, “China’s Great Famine: 40 Years Later” (web page), BMJ : British Medical Journal, accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1127087/. To compound the public seizure of land and means of production, the government also took control of all grain storage and enforced that policy “with virulent anti-hiding campaigns.”5Xin Meng et al., “The Institutional Causes of China’s Great Famine, 1959-1961,” The Review of Economic Studies 82, no. 4 (2015): 1572, accessed December 20, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43869477.

Food and grain in rural areas were distributed through communal kitchens, the final cog in the CCP’s agricultural machine. Each kitchen was tied to a specific People’s Commune, and the government banned peasants from moving to other parts of the country. Thus, agriculturalists were only able to “eat from the amount distributed to their collective. When that food was insufficient, famine occurred.”6Xin Meng et al., “The Institutional Causes,” 15. The CCP’s seizure of every element of China’s agricultural machine meant that, upon failure to sustain the entire country, the Chinese people had no other safety nets onto which they could fall; if the government failed to feed each and every peasant, they had no choice but to starve. And that is exactly what happened to an estimated 46 million people in the three-year period starting in 1959.

The most substantial institutional cause of the Great Chinese Famine was the occurrence of the radical grain target setting. Much of the agriculture harvested in rural regions of China was procured by the CCP for myriad uses that included food for those in cities and for steelworkers and as a form of payment to foreign governments. In and of itself, the procurement of grain for these purposes is not a harmful act; an effective communist society would successfully distribute food to all citizens, not just those who farmed it themselves. However, the targets Chairman Mao set were extreme and often left rural Chinese communities with little to no grain for themselves after procurement.7Chang Liu and Li-An Zhou, “Radical Target Setting and China’s Great Famine:” 2, accessed December 20, 2020, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3075015. Most quotas were set on the eve of the Great Chinese Famine, and even though grain production varied widely over the subsequent three years, the quotas remained the same.8Liu and Zhou, “Radical Target Setting,” 3. The Great Chinese Famine was effectively a function of the CCP’s failure to equitably handle the distribution of grain.

Across China, millions of citizens began dying as a result of these quotas and a few other notable institutional causes: the CCP’s adherence to faulty biological theories, natural disaster, and grain export. Strict adherence to faulty biological theories such as “close planting” decreased grain output.9Sam Kean, “The Soviet Era’s Deadliest Scientist Is Regaining Popularity in Russia,” The Atlantic, accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/12/trofim-lysenko-soviet-union-russia/548786/. In addition, the CCP exported grain internationally to both pay off its debts and bolster public image.10Liu and Zhou, “Radical Target Setting,” 5. Finally, there was a drought in China between 1960 and 1961, which extensive research suggests only exacerbated the famine. However, to this day, the CCP denies any fault for the famine and attributes all deaths to the drought.11Smil, “China’s Great Famine.”

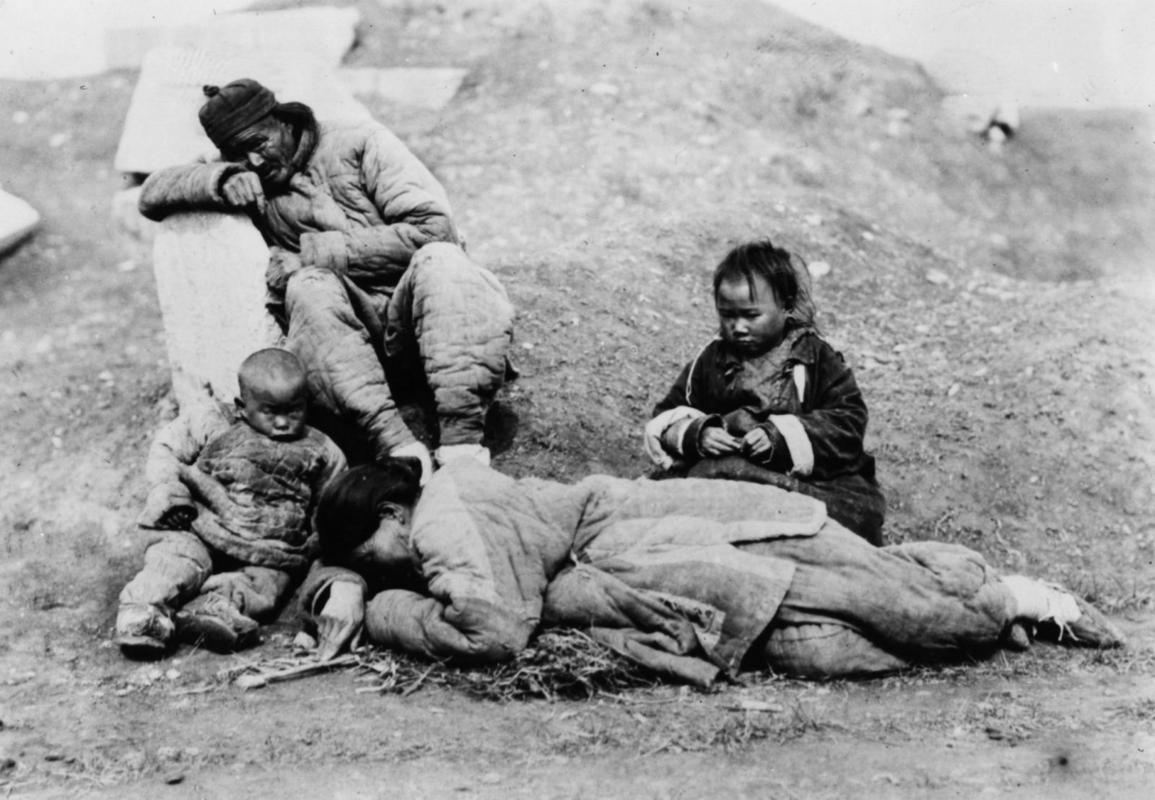

While the institutional causes of the Great Chinese Famine are critically important to understand how it began and played out, the suffering that Chinese citizens themselves experienced is not to be overlooked. As famine swept across the country, peasants found themselves adversely affected and largely helpless. The vast majority of deaths occurred within a six-month period in 1960, and “in some regions, nearly every family experienced at least one death from starvation, and some families were completely wiped out. Entire villages were left without a single inhabitant.”12 Jisheng, Tombstone, 13. No individuals were left untouched by the wrath of the Great Chinese Famine.

When grain stores in communes ran dry, peasants found themselves with no recourse to obtain food to eat and a government that did not care enough to feed them. As a last resort, villagers turned to wild herbs, stripped the bark from trees, and ate bird droppings, vermin, and cotton to fill their stomachs with anything they could.13Jisheng, Tombstone, 14. Once those resources had been exhausted, thousands of Chinese people turned to human flesh: “Cannibalism was no longer exceptional […] during the Great Famine, some families resorted to eating their own children.”14Jisheng, Tombstone, 14. As millions of people died of starvation across China, their bodies began to pile up; some villages transported them by truckload to mass graves, others did not have the energy to bury their dead properly so limbs stuck out from the ground, and others simply left their deceased on the side of the road or in homes where “rats gnawed at their noses and eyes.”15Jisheng, Tombstone, 13. Although the human mind cannot comprehend the amount of loss suffered by the Chinese people between the years of 1959 and 1961, understanding the gruesome conditions that Mao’s regime forced upon its citizens is essential to examining the horror of the Great Chinese Famine.

Image 1,16“Great Chinese Famine,” Wikipedia, accessed December 20, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Chinese_Famine#/media/File:People’s_commune_canteen.jpg. Image 2.17Grace Barnott, “The Story of the Worst Famine in History – ‘The Great Chinese Famine,’” Guestlist, accessed December 20, 2020, https://guestlist.net/article/92223/the-story-of-the-worst-famine-in-history-the-great-chinese-famine.