The line between a natural and anthropocentric disaster is often blurry and muddied by political motives. In the case of famine, that distinction becomes even more ambiguous, as the root cause of famine is lack of food, which itself is a natural substance. However, the nuance in that point runs extremely deep; why a lack of food arose can be the result of drought or floods, but most modern societies have massive food stores to prevent such instances from occurring. Amartya Sen, an economist and philosopher, argues that no famine has ever occurred in a democracy: “The direct penalties of a famine are borne by one group of people and political decisions are taken by another. The rulers never starve. But when a government is accountable to the local populace it too has good reasons to do its best to eradicate famines. Democracy, via electoral politics, passes on the price of famines to the rulers as well.”1Vaclav Smil, “China’s Great Famine: 40 Years Later” (web page), BMJ : British Medical Journal, accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1127087/. During the Great Leap Forward, China was controlled by a totalitarian, authoritarian regime. There were no avenues for the masses to have their voices heard and no repercussions for Mao’s actions.

To this day, however, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propagates the idea that the Great Chinese Famine was a result of natural disaster rather than intentional mismanagement of food stores and grain distribution. Chinese textbooks refer to the years of the famine as “three Years of Natural Disaster.”2Helen Gao, “After 50 Years of Silence, China Slowly Confronts the ‘Great Leap Forward,’” The Atlantic, accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/05/after-50-years-of-silence-china-slowly-confronts-the-great-leap-forward/257797/. This calculated political move aligns with the CCP’s history of silence on Mao’s regime: “Even today, Mao is an untouchable icon. As the founding father of Red China, he holds the nation together and gives legitimacy to the current authorities. So as not to damage his image, the Chinese Communist Party has maintained a deafening silence on [the Great Chinese Famine] for 50 years.”31:13-1:33, Mao’s Great Famine, directed by Patrick Cobuat and Philippe Grangereau, (2011; New York: Filmakers Library), Youtube Video, accessed December 20, 2020, https://youtu.be/FcvAz9t3kDw. The CCP’s description of the famine as a natural disaster is essential to maintaining the legitimacy of its authority and rule. The truth of the matter, however, is starkly different.

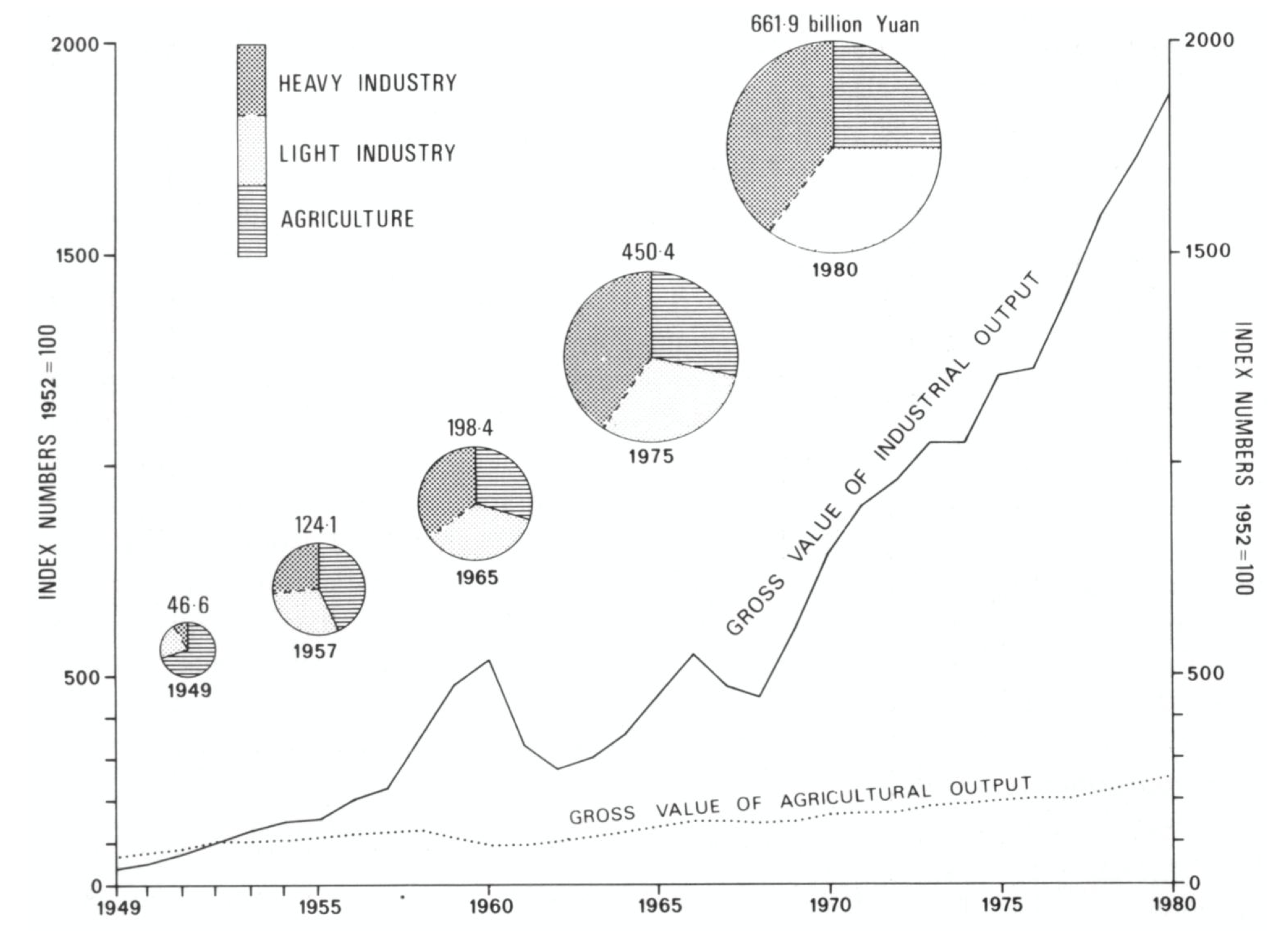

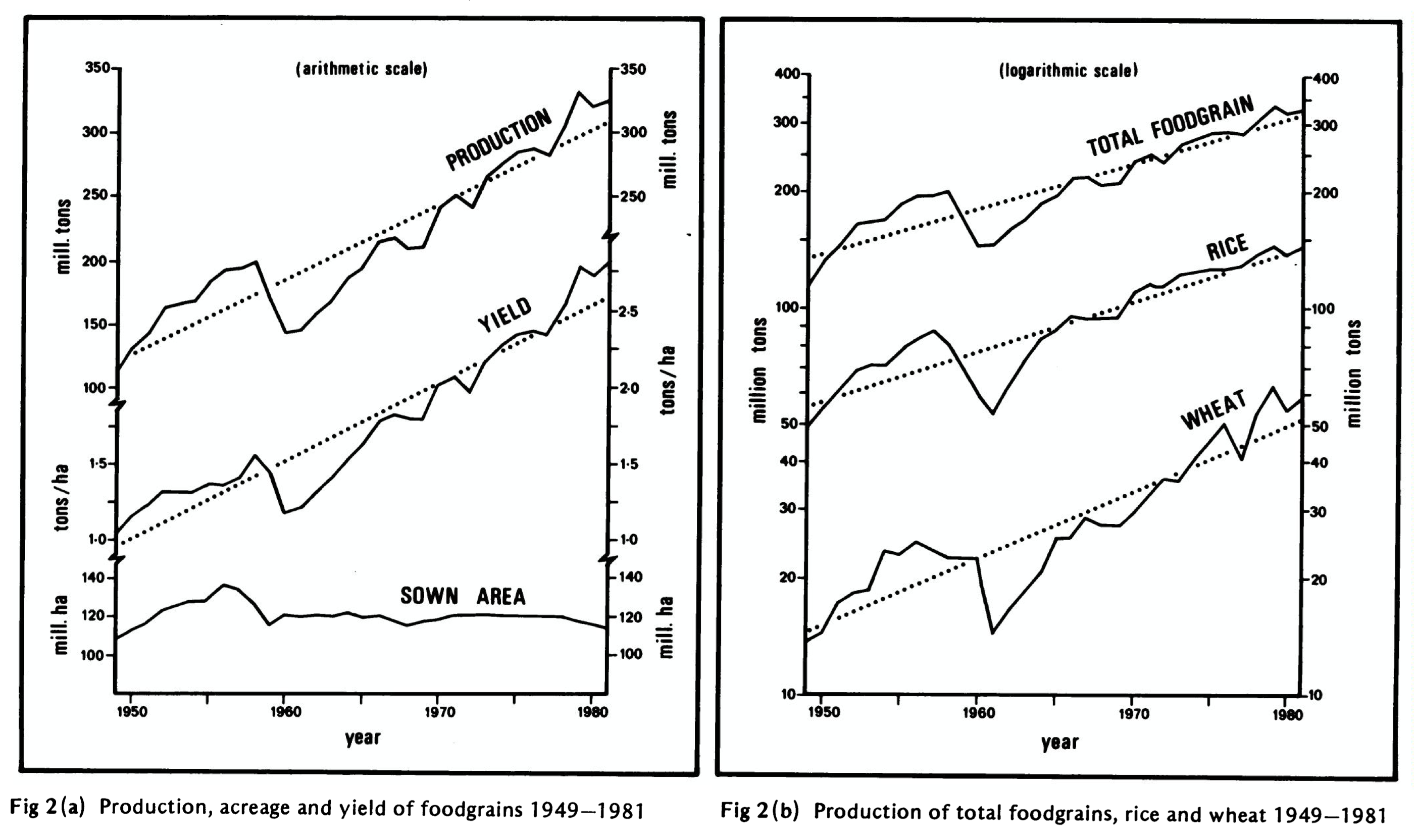

Grain production in China plummeted from 1958 through 1966. In 1958, on the precipice of famine, China produced 200 million tons of food; that number dropped to a low of 143 million tons in 1960, and it took the subsequent six years to build back up to above 200 million tons.4A. J. Jowett, “China’s Foodgrains: Production and Performance, 1949—1981,” GeoJournal 10, no. 4 (1985): 376, accessed December 20, 2020, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41143848. As described above, typical Chinese literature and propaganda attribute this decrease in agricultural production to “severe drought.” If severe drought had caused the decreased crop output during the 1960s, it would not be unreasonable to see similar decreases in crop production during other times of severe drought in Chinese history. However, the crop output in the early 1990s, during one of the “worst droughts and floods in China’s modern history,” does not show nearly as strong a correlation.5Smil, “China’s Great Famine.” When scaled to match each other in ratio, the decrease in crop output in the 1958-60 time frame is 3.8 times greater than that during the early 1990s.6200 million tons*x = 400 million tons, x = 2.35. Decrease of 57 million tons*x = 134 million tons adjusted differential. 35 million tons*y = 134 million tons, y = 3.8 The official Chinese narrative of the three years of famine assumes a strong relationship between drought and crop failure; that relationship is not historically borne out.

The CCP pushed the political agenda that the Great Chinese Famine was the result of drought, but because the tie between natural causes and crop failure is weak at best, the explanation for the decreased crop yield must lie in anthropocentric origins. The most substantial of these causes are close-planting, deep plowing, and the hectarage of land tilled. Trofim Lysenko, a Soviet communist and agronomist, devised a theory called “close-planting” in which seeds of the same species were planted in very high concentrations near each other. This theory was based on the false notion that seeds of the same species would not compete with one another.7Sam Kean, “The Soviet Era’s Deadliest Scientist Is Regaining Popularity in Russia,” The Atlantic, accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/12/trofim-lysenko-soviet-union-russia/548786/. Mao’s regime implemented Lysenko’s theories and forced many farmers to comply with them, which significantly lowered grain yield.8Yang Jisheng, Tombstone (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2012), 259. Similarly, Mao believed in the unsubstantiated method of deep plowing and forced farmers to spend time plowing deeper than necessary, both wasting energy and not increasing yield.9James Kai-sing Kung and Justin Yifu Lin, “The Causes of China’s Great Leap Famine, 1959-1961,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, no. 1 (2003): 71, accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/380584. Finally, the number of hectares sowed dropped from 157.2 million in 1957 to 140.2 million in 1962, largely a result of the forced transition from privately owned farms to People’s Communes.10Jowett, “China’s Foodgrains,” 379. Perhaps the most significant factor that contributed to famine itself was the extreme grain procurement enforced by the Chinese Communist Party, which forced the People’s Communes to hand over so much food that they were left without enough sustenance for themselves. This aspect of the famine is examined in depth here.

Clearly, the decrease in crop production—itself a major contributor to the Great Chinese Famine—was not purely a result of natural disaster. The Chinese Communist Party’s ongoing efforts to paint it as such are emblematic of its ongoing effort to shirk responsibility for the death of 36 million Chinese citizens. Admitting fault—or at least accepting an iota of responsibility for the famine—would mean criticizing Chairman Mao’s policies, the Great Leap Forward, and much of the lore on which the present Chinese government is founded.

Figure 1,11Jowett, “China’s Foodgrains,” 375 Figures 2 and 3.12Jowett, “China’s Foodgrains,” 374